| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 10, Number 5, May 2018, pages 384-390

Impact of Drug Induced Long QT Syndrome: A Systematic Review

Karuppiah Arunachalama, e, Seetha Lakshmananb, Abhishek Maana, Narendra Kumarc, Paari Dominicd

aWarren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA

bAsian Institute of Medicine, Science and Technology, Sungai Petani, Malaysia, Malaysia

cParas HMRI Hospital, Patna, India

dCenter for Cardiovascular Diseases and Sciences, LSU Health Sciences Center, Shreveport, Louisiana, LA, USA

eCorresponding Author: Karuppiah Arunachalam, 593 Eddy Street, Providence, RI 02896, USA

Manuscript submitted January 9, 2018, accepted February 6, 2018

Short title: Outcomes of Drug Induced Long QT Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3338w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Drug induced long QT syndrome is quite common in daily clinical practice but its impact is unknown.

Methods: PubMed and EMBASE databases (until May 2, 2017) were searched to identify studies reporting drug induced long QT syndrome and followed the PRISMA guidelines. The main outcomes measured in these studies were QTc prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, torsade de pointes (TdP) and death.

Results: Out of 176 non-duplicate reports, 36 studies satisfied inclusion criteria and provided data on patients exposed to drugs that can potentially cause long QT. Totally, 14,756 patients were exposed and 930 patients (6.3%) were found to have QTc prolongation. The number of males was 6,400 and females were 5,723 patients. The mean age of the patients was 43.8 ± 9.36 years. Ventricular arrhythmias were found in 379 patients (2.6%), 26 patients were found to have premature atrial contractions (PACs) and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). TdP was found in 49 patients (0.33 %), sudden cardiac death (SCD) was found in five patients and 586 patients were found to have all-cause mortality.

Conclusions: Around 6% of patients have risk of QT prolongation when exposed but only 0.3% developed TdP and 2.6% developed ventricular arrhythmias. Risk of developing arrhythmias is higher with concomitant use of multiple QT prolonging drugs.

Keywords: QTc prolongation; Torsades de pointes; Sudden cardiac death

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The QT interval reflects electrical depolarization and repolarization of both ventricles. Rate-corrected QT (QTc) intervals are almost identical in males and females till late adolescence (0.37 - 0.44 s). After which, the normal range of QTc interval is slightly longer in females (< 0.47s) than in males (< 0.45s) [1].

Prolonged QT interval seen on electrocardiogram (EKG) is known as Long QT syndrome. This syndrome is often associated with increased risk of arrhythmias especially torsades de pointes (TdP), a distinctive form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia characterized by changes in the amplitude and deformation of QRS complexes around the isoelectric line. TdP may potentially degenerate into ventricular fibrillation (VF) and cause sudden cardiac death (SCD), if not treated promptly.

Acquired forms of Long QT syndrome are usually provoked by the presence of extrinsic triggers such as QT-prolonging drugs, hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and bradycardia. However, the most common culprit is those associated with QT prolonging drugs which are still regularly being used in clinical practice, namely antihistamines, antibiotics, antidepressants, and prokinetics. In recent days, more and more drugs have started identifying QTc prolongation as their adverse effect. Nonetheless, these drugs are still being prescribed by clinicians probably because they are unaware of the relative risk of QTc prolongations and their impact on patients. There are plenty of case reports and systematic review based on case reports published on drug induced QTc prolongation. In this systematic review of research articles, we have focused on identifying the common drugs that have been known to prolong QTc and analyze their cardiac side effects and their impact on mortality.

| Methods | ▴Top |

This systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines [2].

Data sources and searches

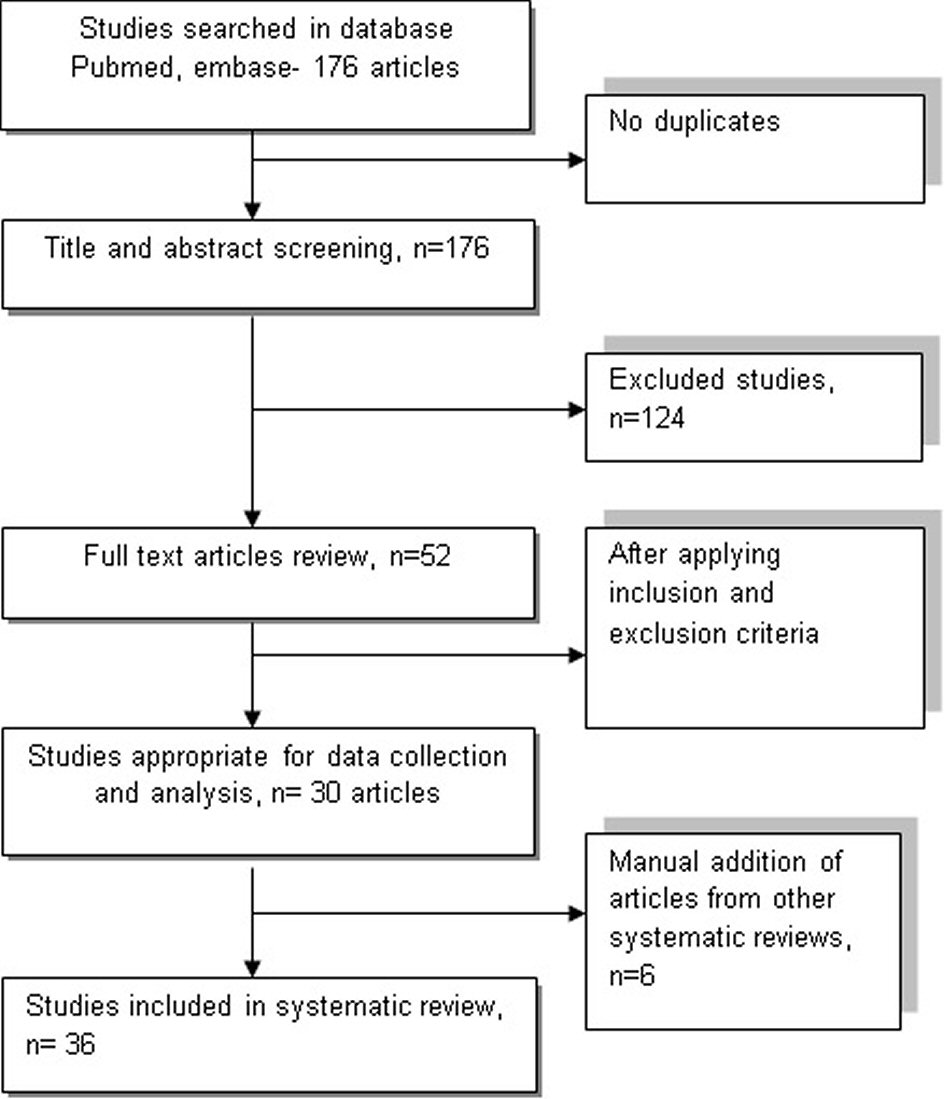

Comprehensive search was conducted on PubMed and EMBASE databases by using the term ((drug induced QT syndrome) or (medication induced QT syndrome)) and ((outcome) or (adverse events)) for studies published until May 2, 2017. Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies in English and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Duplicates were removed prior to study selection. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were assessed independently for eligibility by two authors. The search was supplemented by screening the studies included in similar systematic reviews and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Flowchart illustrates the process of including and excluding studies following PRISMA guidelines using PubMed and EMBASE database. |

Study selection

Inclusion criteria include: 1) studies analyzing QT prolongation due to medications, 2) more than 10 subjects, 3) studies that identify QT measurement or change in QTc, drug usage, measured outcomes and other cardiac side effects.

Exclusion criteria include: 1) age less than 18 years old, 2) patients with congenital long QT syndrome, 3) case reports, case series, review articles, 4) studies with less than 10 subjects, 5) studies that doesn’t discuss outcomes, 6) articles in language other than English, 8) studies that reports only events without number of patients screened or affected, 9) studies using off market drugs and experimental drugs.

Outcomes of interest

The primary outcome was to identify drugs causing QT prolongation compared to baseline. Secondary outcomes included their impact and other side effects observed among the patients taking these drugs namely, ventricular arrhythmias, TdP and death.

| Results | ▴Top |

Out of 176 non-duplicate reports, 36 studies satisfied inclusion criteria and provided data on patients exposed to drugs that can potentially cause long QT.

Geographically, 12/36 studies were done in USA, multicenter studies account for 11/36 studies, one study was done in UK/France/Germany/Turkey/Greece/Taiwan/Iran, two studies were done in Switzerland. Study design distributions were: cross sectional studies in 3/36, prospective observational in 3/36, retrospective studies in 10/36 and randomized controlled trials in 19/36 (Table 1, [3-38]).

Click to view | Table 1. Summary of Studies With Age, Type of Study, Gender, Drugs Used and Distribution of QTc Prolongation |

Drugs used in studying QTc prolongation were distributed as follows out of 36 studies: multiple drugs in 10/36 studies, haloperidol in 6/36 studies, olanzapine, ziprasidone and quetiapine in 2/36, risperidone in 5/36, methadone in 4/36, aripiprazole in 7/36, Other drugs (clozapine/chlorpromazine/dofetilide/capecitabine/azithromycin/amisulpride/ citalopram/ escitalopram/sotalol/paliperidone ER/ondansetron/fluoroquinolone antibiotics/azithromycin/sertindole/LAAM/iloperidone) one each out of 36 studies. Multiple drugs is designated as a variable when a study uses more than two drugs in the study population or more than two drugs in the same patient.

Totally, 14,756 patients were exposed and 930 patients (6.3%) were found to have QTc prolongation. Males were 6,400, females were 5,723 patients and mean age of the patients was 43.8 ± 9.36 (Table 1). Ventricular arrhythmias were found in 379 patients (2.6%), 26 patients were found to have PACs and PVCs. TdP was found in 49 patients (0.33 %), SCD was found in five patients and 586 were found to have all-cause mortality. Only two studies reported ventricular arrhythmias [3, 36]; two studies reported TdP [9, 19]; one study reported SCD [9]; and four studies reported death [18-20, 36]. Remaining studies either didn’t report ventricular arrhythmias or didn’t have any episodes of ventricular arrhythmias. In one of the studies using methadone, 43 out of 59 patients were found to have TdP [19], remaining six patients who had TdP were result of using multiple drugs [9]. The study is based on 5,503 reported adverse events from MedWatch database (Table 2, [3-38]).

Click to view | Table 2. Summary of Distribution of Different Types of Arrhythmias Among Qatients With QT Prolonging Drugs |

Duration of the prospective studies was mostly 6 months to 2 years where as one of the retrospective study reviewed a database for 33 years. Remaining retrospective study usually lasted from 1 to 5 years. The setting in which patients were studies either inpatient or outpatient except for one study where the setting was ICU and emergency room. QTc interval was measured predominantly by Bazett’s formula except for few using Fridericia’s formula. QTc interval was measured using routine 12-lead EKG in all the studies.

Changes in QTc were discussed only in 11 studies. QTc decreased in risperidone group in a large study of 1,362 patients compared to haloperidol [31]. Same effect with use of risperidone was seen in a study comparing the drug against olanzapine [25]. But the results are not consistent with another two studies where risperidone compared to olanzapine and aripiprazole had prolonged QTc compared to the latter drugs [24, 26]. In a study of patients with methadone, QTc was prolonged nearly by 66 ms [13]. Van der sijs et al studied use of multiple drugs (haloperidol, amiodarone, sotalol), QTc prolongation was found to be 59.76 ms [18].

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Drug-induced Long QT syndrome holds an undesirable risk of arrhythmias and SCD causing substantial concern to clinicians. Although more than 150 drugs have already been implicated (www.qtdrugs.org), more are continuously being identified by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This has led to the withdrawal of many newly developing, otherwise useful drugs after noticing a small number of cases with QT prolongation and arrhythmias in phase 2 and 3 stages of drug trials. Drugs that have been taken off the market in the United States and other countries because of their increased risk of TdP are namely, ondansetron, cisapride, terfenadine, astemizole.

In our qualitative approach, methadone was reported in four studies and found to have highest proportion of patients with QTc prolongation and TdP in single study. Cumulatively, concomitant use of multiple QT prolonging drugs is found to have largest patient population with significant QTc prolongation. Use of multiple QT prolonging drugs was studied most commonly followed by use of drugs such as haloperidol, risperidone and aripiprazole individually. Schizophrenia is the most common diagnosis in which outcomes of QT prolongation was evaluated. Usage of multiple QT prolonging drugs and sertindole is associated with SCD. Researches which studied azithromycin, methadone and sertindole, multiple QT prolonging drugs were found to have reported all-cause mortality. Amiodarone, sotalol and dofetilide are notorious for significant QTc prolongation and especially the risk of ventricular arrhythmias TdP is higher. Most commonly studied non-cardiac drugs are antipsychotics like haloperidol, risperidone, olanzapine and aripiprazole. QTc prolongation doesn’t correspond to ventricular arrhythmias or TdP in non-cardiac drugs.

On a study of 172 patients, the most common cause for QTc prolongation was QTc interval-prolonging medication and was deemed most responsible in 48% of patients, with 25% of these patients taking ≥ two offending drugs [39]. Out of seven patients who died with VF, cause of death was myocardial ischemia in three patients and severe heart failure in three patients and one had VF during seizure. Antidepressants caused QTc prolongation in 53 patients and amiodarone in 36 patients [39].

TdP was reported in less than 1% with use of amiodarone though it is one of the most common QTc prolonging cardiac drugs [40]. There were no significant differences in mean QTc interval duration in users of citalopram and paroxetine and their corresponding reference patients according to study by Van Haelst et al. The use of an SSRI by elderly surgical patients was not associated with the occurrence of QT interval prolongation [36]. Hasnain et al in their comprehensive review reported 28 cases of TdP, six (21.4 %) experienced it with QTc interval < 500 ms; 75 % of TdP cases occurred at therapeutic doses [41].

Acquired QTc interval prolongation is more common than congenital and is typically ascribed to drugs that incidentally block the IKr current or systemic illness that indirectly prolongs the QTc interval through ill-defined mechanisms. Drugs block the delayed rectifier potassium channel which is coded by human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG). The distinct molecular structure of hERG channel makes it more susceptible to medications. IKr current plays an important role in phase 3 of ventricular action potential (ventricular repolarization) [42]. Prolongation of ventricular action potential due to blockage of delayed rectifier potassium channel leads to fluctuation in membrane potential leading to development of early after depolarization (EAD). After reaching a certain threshold with wider heterogeneity, EADs can lead to reentrant excitation and TdP which can result in SCD [43].

Strengths and limitations

There is significant number of randomized control trials which increases the strength of this systematic review. Baseline QTc and measured QTc after the use of specific QT prolonging drug was either not reported or discussed in a large number of studies. There is an inconsistency in measuring the risk of QTc prolongation in most of the studies. There are also unclear reports of ventricular arrhythmias or TdP studied in the included articles.

Conclusions

Acquired QTc prolongation due to drugs is the most common cause for QTc prolongation observed in clinical practice. Caution should be exercised in case of usage of cardiac drugs like amiodarone, sotalol and dofetilide as they are increasingly associated with fatal arrhythmias. Though antipsychotics and antibiotics could cause significant QTc prolongation, ventricular tachycardia or TdP is more common with simultaneous use of two or more other QT prolonging drugs. More detailed randomized controlled studies with accurate description of baseline QTc, change in QTc interval and appropriate report of any significant ventricular arrhythmias with usage of multiple QTc prolonging drugs should be performed in future.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Grant Support

None.

Author Contributions

KA: design of the study, data collection, preparation of manuscript and review; SL: design of the study, data collection; AM, NK: review of manuscript; PD: critical and final review of manuscript.

Disclosure

None

Abbreviations

TdP: torsades de pointes; EAD: early after depolarization; PAC: premature atrial contraction; PVC: premature ventricular contraction

| References | ▴Top |

- Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W. QT interval: how to measure it and what is "normal". J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17(3):333-336.

doi pubmed - Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, Tierney JF, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1657-1665.

doi pubmed - Agusala K, Oesterle A, Kulkarni C, Caprio T, Subacius H, Passman R. Risk prediction for adverse events during initiation of sotalol and dofetilide for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;38(4):490-498.

doi pubmed - Armahizer MJ, Seybert AL, Smithburger PL, Kane-Gill SL. Drug-drug interactions contributing to QT prolongation in cardiac intensive care units. J Crit Care. 2013;28(3):243-249.

doi pubmed - Cunnington AL, Hood K, White L. Outcomes of screening Parkinson’s patients for QTc prolongation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(11):1000-1003.

doi pubmed - Hough DW, Natarajan J, Vandebosch A, Rossenu S, Kramer M, Eerdekens M. Evaluation of the effect of paliperidone extended release and quetiapine on corrected QT intervals: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(1):25-34.

doi pubmed - Letsas KP, Efremidis M, Kounas SP, Pappas LK, Gavrielatos G, Alexanian IP, Dimopoulos NP, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with drug-induced QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes: identification of risk factors. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98(4):208-212.

doi pubmed - Moffett PM, Cartwright L, Grossart EA, O’Keefe D, Kang CS. Intravenous Ondansetron and the QT Interval in Adult Emergency Department Patients: An Observational Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(1):102-105.

doi pubmed - Niedrig D, Maechler S, Hoppe L, Corti N, Kovari H, Russmann S. Drug safety of macrolide and quinolone antibiotics in a tertiary care hospital: administration of interacting co-medication and QT prolongation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(7):859-867.

doi pubmed - Perrin-Terrin A, Pathak A, Lapeyre-Mestre M. QT interval prolongation: prevalence, risk factors and pharmacovigilance data among methadone-treated patients in France. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2011;25(4):503-510.

doi pubmed - Potkin SG, Preskorn S, Hochfeld M, Meng X. A thorough QTc study of 3 doses of iloperidone including metabolic inhibition via CYP2D6 and/or CYP3A4 and a comparison to quetiapine and ziprasidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):3-10.

doi pubmed - Wieneke H, Conrads H, Wolstein J, Breuckmann F, Gastpar M, Erbel R, Scherbaum N. Levo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM) induced QTc-prolongation - results from a controlled clinical trial. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14(1):7-12.

doi pubmed - Beyraghi N, Rajabi F, Hajsheikholeslami F. Prevalence of QTc interval changes in acute psychiatric care: a cross-sectional study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(3):227-231.

doi pubmed - Koca D, Salman T, Unek IT, Oztop I, Ellidokuz H, Eren M, Yilmaz U. Clinical and electrocardiography changes in patients treated with capecitabine. Chemotherapy. 2011;57(5):381-387.

doi pubmed - Lee RA, Guyton A, Kunz D, Cutter GR, Hoesley CJ. Evaluation of baseline corrected QT interval and azithromycin prescriptions in an academic medical center. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):15-20.

doi pubmed - Pearson EC, Woosley RL. QT prolongation and torsades de pointes among methadone users: reports to the FDA spontaneous reporting system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(11):747-753.

doi pubmed - Price LC, Wobeter B, Delate T, Kurz D, Shanahan R. Methadone for pain and the risk of adverse cardiac outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(3):333-342 e331.

- van der Sijs H, Kowlesar R, Klootwijk AP, Nelwan SP, Vulto AG, van Gelder T. Clinically relevant QTc prolongation due to overridden drug-drug interaction alerts: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(3):347-354.

doi pubmed - Azorin JM, Strub N, Loft H. A double-blind, controlled study of sertindole versus risperidone in the treatment of moderate-to-severe schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(1):49-56.

doi pubmed - Chan HY, Lin WW, Lin SK, Hwang TJ, Su TP, Chiang SC, Hwu HG. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in the acute treatment of schizophrenia in Chinese patients with risperidone as an active control: a randomized trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(1):29-36.

doi pubmed - Beasley CM, Jr., Tollefson G, Tran P, Satterlee W, Sanger T, Hamilton S. Olanzapine versus placebo and haloperidol: acute phase results of the North American double-blind olanzapine trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14(2):111-123.

doi - Conley RR, Mahmoud R. A randomized double-blind study of risperidone and olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):765-774.

doi pubmed - Fleischhacker WW, McQuade RD, Marcus RN, Archibald D, Swanink R, Carson WH. A double-blind, randomized comparative study of aripiprazole and olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(6):510-517.

doi pubmed - Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR, McQuade RD, Ingenito GG, Zimbroff DL, Ali MW. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(9):763-771.

doi pubmed - Kane JM, Khanna S, Rajadhyaksha S, Giller E. Efficacy and tolerability of ziprasidone in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(1):21-28.

doi pubmed - McEvoy JP, Daniel DG, Carson WH, Jr., McQuade RD, Marcus RN. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole 10, 15 or 20 mg/day for the treatment of patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(11):895-905.

doi pubmed - Min SK, Rhee CS, Kim CE, Kang DY. Risperidone versus haloperidol in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients: a parallel group double-blind comparative trial. Yonsei Med J. 1993;34(2):179-190.

doi pubmed - Peuskens J. Risperidone in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia: a multi-national, multi-centre, double-blind, parallel-group study versus haloperidol. Risperidone Study Group. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(6):712-726; discussion 727-733.

doi pubmed - Peuskens J, Bech P, Moller HJ, Bale R, Fleurot O, Rein W. Amisulpride vs. risperidone in the treatment of acute exacerbations of schizophrenia. Amisulpride study group. Psychiatry Res. 1999;88(2):107-117.

doi - Potkin SG, Saha AR, Kujawa MJ, Carson WH, Ali M, Stock E, Stringfellow J, et al. Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with a novel mechanism of action, and risperidone vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):681-690.

doi pubmed - Sacchetti E, Galluzzo A, Valsecchi P, Romeo F, Gorini B, Warrington L, Group IS. Ziprasidone vs clozapine in schizophrenia patients refractory to multiple antipsychotic treatments: the MOZART study. Schizophr Res. 2009;110(1-3):80-89.

doi pubmed - Tran PV, Hamilton SH, Kuntz AJ, Potvin JH, Andersen SW, Beasley C, Jr., Tollefson GD. Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(5):407-418.

doi pubmed - Vieta E, Franco C. [Advances in the treatment of mania: aripiprazole]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2008;36(3):158-164.

pubmed - Haixu Y, Jinqiu L, Ying L, Yanli Z, Fei X, Yu Z, Pinrui L, et al. Aquired long QT syndrome may contribute to the all cause mortality in hospitalized patients-a pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(16):C104.

doi - Niedrig D, Muller S, Gott C, Greil W, Russmann S. Antidepressant use and outcomes in combination with contraindicated comedication in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25:588.

- van Haelst IM, van Klei WA, Doodeman HJ, Warnier MJ, De Bruin ML, Kalkman CJ, Egberts TC. QT interval prolongation in users of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in an elderly surgical population: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):15-21.

doi pubmed - Manini AF, Stimmel B, Vlahov D. Racial susceptibility for QT prolongation in acute drug overdoses. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47(2):244-250.

doi pubmed - Kasper S, Lerman MN, McQuade RD, Saha A, Carson WH, Ali M, Archibald D, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole vs. haloperidol for long-term maintenance treatment following acute relapse of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6(4):325-337.

doi pubmed - Laksman Z, Momciu B, Seong YW, Burrows P, Conacher S, Manlucu J, Leong-Sit P, et al. A detailed description and assessment of outcomes of patients with hospital recorded QTc prolongation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(7):907-911.

doi pubmed - Vorperian VR, Havighurst TC, Miller S, January CT. Adverse effects of low dose amiodarone: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(3):791-798.

doi - Hasnain M, Vieweg WV. QTc interval prolongation and torsade de pointes associated with second-generation antipsychotics and antidepressants: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(10):887-920.

doi pubmed - Roden DM, Viswanathan PC. Genetics of acquired long QT syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2025-2032.

doi pubmed - Nguyen AP, Sarmast SA, Kowal RC, Schussler JM. Cardiac arrest due to torsades de pointes in a patient with complete heart block: the "R-on-T" phenomenon. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2010;23(4):361-362.

doi

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.