| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 10, Number 3, March 2018, pages 174-177

Do All Acute Stroke Patients Receiving tPA Require ICU Admission?

Farid Sadakaa, b, c, Amar Jadhava, b, Jacklyn O’Briena, b, Steven Trottiera, b

aMercy Hospital St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

bSt. Louis University, St. Louis, MO, USA

cCorresponding Author: Farid Sadaka, Mercy Hospital St. Louis, 625 S. New Ballas Rd, Suite 7020, St. Louis, MO 63141, USA

Manuscript submitted November 27, 2017, accepted December 27, 2017

Short title: Acute Stroke in ICU

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3283w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Limited resources warrant investigating models for predicting which stroke tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) patients benefit from admission to neurologic intensive care unit (neuroICU).

Methods: This model classifies patients who on day 1 of their ICU admission are predicted to receive one or more of 30 subsequent active life supporting treatments. Two groups of patients were compared: low risk monitor (LRM) (patients who did not receive active treatment (AT) on the first day and whose risk of ever receiving active treatment was ≤ 10%) and AT (patients who received at least one treatment on any day of their ICU admission).

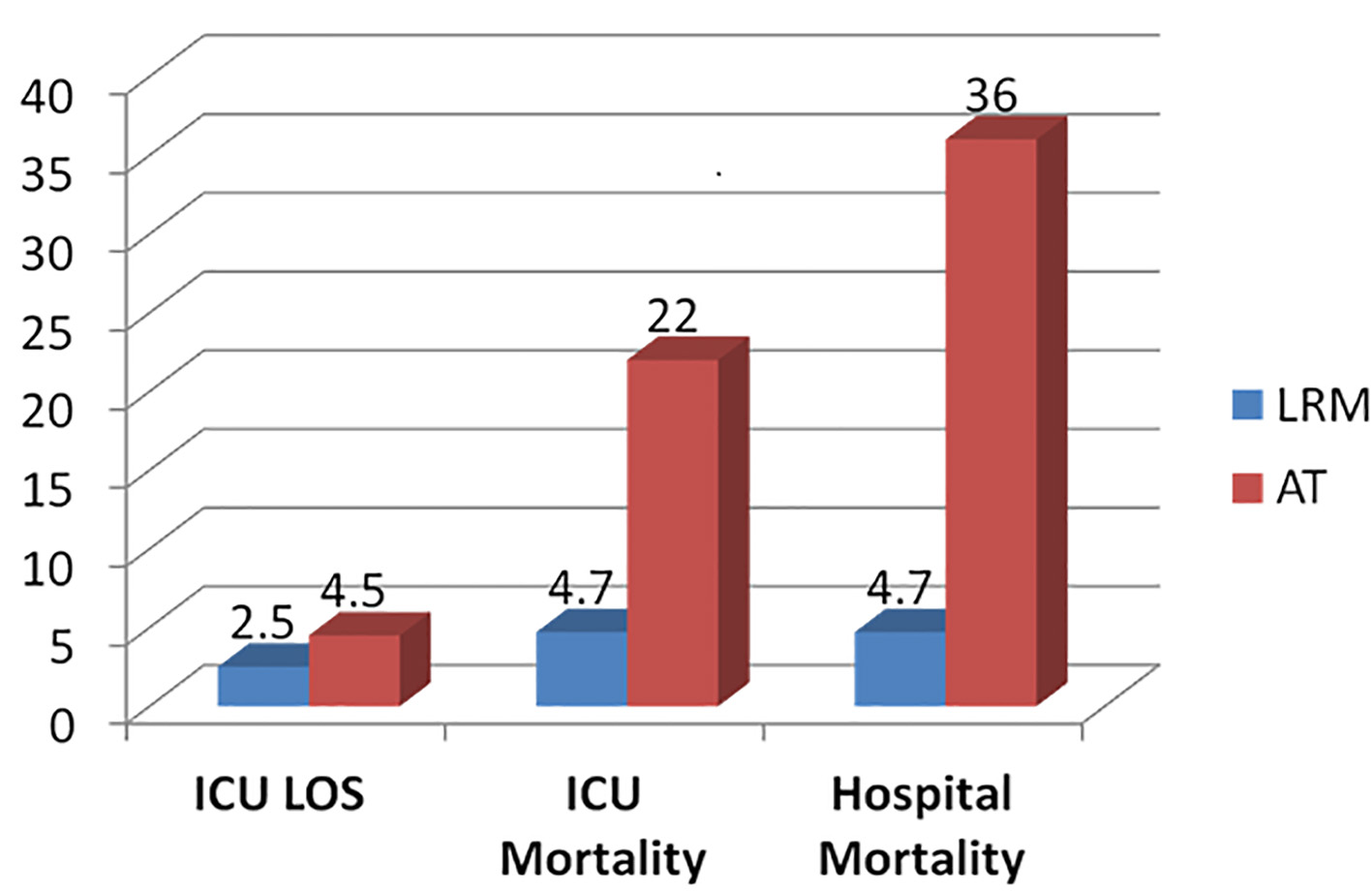

Results: Compared to LRM group (21 patients), AT group (59 patients) had similar age (75 ± 13 vs. 72 ± 17, P = 0.4), similar gender (male: 56% vs. 52%, P = 0.8), similar National Institutes of Health stroke scale (NIHSS, 16 ± 9 vs. 14 ± 8, P = 0.4), and higher Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III scores (62 ± 26 vs. 41 ± 15, P = 0.0008). Compared to LRM group, AT group had longer ICU length of stay (4.5 ± 4.4 vs. 2.5 ± 1.3, P = 0.04), higher ICU mortality (22% vs. 4.7% (one patient DNR/hospice); OR: 5.6; 95% CI: 0.7 - 46.0; P = 0.1), and higher hospital mortality (36% vs. 4.7%; OR: 11; 95% CI: 1.4 - 88.0; P = 0.02).

Conclusion: The outcome of LRM patients with stroke post-tPA suggests that they may not require admission to a formal neuroICU, improving resource use and reducing costs.

Keywords: Neurologic intensive care unit; Stroke; Ischemic stroke; tPA; Utilization review

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) was first approved by the FDA in the United States in 1996 and remains the only medication shown to improve outcomes when given within 3 - 4.5 h after ischemic stroke. Although tPA remains underutilized in patients with acute ischemic stroke, nonetheless, its use is steadily increasing [1]. Patients with acute ischemic stroke who receive tPA are admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) for close monitoring and frequent neurochecks, especially because of risk of major bleeding with tPA.

The concept of resource allocation on the grounds of relative medical benefit is often referred to as triaging: “the process in medicine of finding the most appropriate disposition for a patient based on an assessment of the patient’s illness and its urgency”. A little more than 50 years ago, hospitals opened ICUs with the purpose of caring for the sickest patients, using the newest technology. Today, critical care in the United States costs more than $80 billion annually [2]. Most of the studies on rationing healthcare and resource allocation regarding ICU admission focused on patients who might be too sick to benefit [3].

In a recent study, the outcome for low risk monitor (LRM) patients suggests they may be treated outside of ICU [4]. That study presented a new model for identifying patients who might be too well to benefit from ICU care. Limited resources, neurointensivists, and neurologic intensive care unit (neuroICU) beds warrant investigating models for predicting who will benefit from admission to neuroICU. In this study, we apply the same model to identify patients with ischemic stroke and received intravenous tPA who might not need to be admitted to the neuroICU.

| Methods | ▴Top |

The Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) outcomes database was used to retrospectively identify ischemic stroke patients who received tPA and admitted to our neuroICU between January 2013 and December 2016. Our 16-bed neuroICU is staffed by intensivists (board certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine in Internal Medicine and Critical Care Medicine and certified by the United Council of Neurologic Subspecialties in Neurocritical Care) 24 h/day. The APACHE outcomes database further classifies patients who on day 1 of their neuroICU admission are predicted to receive or not receive one or more of 30 subsequent active life supporting treatments (Table 1). We compared two groups of patients: LRM (patients who did not receive active treatment on the first day and whose risk of ever receiving active treatment was ≤ 10%) and active treatment (AT) (patients who received at least one of the 30 ICU treatments on any day of their ICU admission). In a previous study [4], data were used to develop and internally and externally validate the APACHE IV risk for active treatment in the ICU. In short, data generated as a result of patient care and recorded in the medical record were collected concurrently or retrospectively for consecutive unselected ICU admissions. Data collected for each patient are shown in Table 2. Detailed descriptions of these demographic, clinical, and physiological items have been previously reported [5, 6].

Click to view | Table 1. Active Life Supporting Treatments |

Click to view | Table 2. Patient Data Collected and Variables Used for Predicting Risk for Active Treatment Based on Intensive Care Unit Day 1 Data |

LRM patients were defined as admissions that did not receive any of the 30 active life supporting treatments listed in Table 1 during their first ICU day. To determine which characteristics influenced risk for AT, a multivariable logistic regression model was developed to estimate the probability that an LRM admission would ever receive AT during the remainder of their ICU stay. The predictor variables in the logistic regression model are listed in Table 2 and were preselected based on previous research [7]. A 10% predicted risk for receiving AT was previously validated as a means for identifying ICU patients with a low versus a high risk for AT [8]. The 10% threshold gave the highest combination of sensitivity and specificity. This model was validated internally and externally in general ICUs [4]. This study intends to apply this model on ischemic stroke patients who received tPA and admitted to a single center neuroICU.

We excluded patients who had been admitted for less than 4 h, and patients younger than 18 years. Data were entered using a software program that included computerized pick lists and automated calculation of physiological means and gradients and error checking. Data collection procedures were based on prior reliability studies [9]. Patient identifiers were removed from the database, and informed consent was waived by our institutional review board. Mean, standard deviation and P values were reported for comparisons. Wilcoxon and Chi-squared statistics were used to determine significance. Significance was considered at the P < 0.05 level.

| Results | ▴Top |

Eighty patients were identified with 21 (26%) in the LRM group, and 59 (74%) in the AT group. Compared to LRM group, AT group had similar age in years (75 ± 13 vs. 72 ± 17, P = 0.4), similar gender (male: 56% vs. 52%, P = 0.8), similar pre-tPA National Institutes of Health stroke scale (NIHSS) (16 ± 9 vs. 14 ± 8, P = 0.4), and higher APACHE III scores (62 ± 26 vs. 41 ± 15, P = 0.0008) (Table 3). ICU length of stay in days was 2.5 ± 1.3 for the LRM group versus 4.5 ± 4.4 for the AT group (P = 0.04). ICU mortality was 4.7% (one patient DNR/hospice care) for the LRM group compared to 22% for the AT group (OR: 5.6; 95% CI: 0.7 - 46.0, P = 0.1). Hospital mortality was 4.7% for the LRM group compared to 36% for the AT group (OR: 11; 95% CI: 1.4 - 88.0, P = 0.02) (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Click to view | Table 3. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of the Active Treatment Group and the Low Risk Monitor Group |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Outcome comparisons between the low risk monitor (LRM) and active treatment (AT) groups. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this study, we present a model that identifies a group of acute ischemic stroke patients who received tPA who might be too well to benefit from neuroICU admission. This model is not intended to triage individual admissions because it uses treatment and physiological data obtained during the first ICU day. It can, however, be used to identify patient groups based on characteristics and outcomes retrospectively; that management can be used to formulate policies, protocols, and educational programs pertaining to finding alternatives to admission to neuroICU.

The finding of this study confirms the result of the study by Zimmernan and Kramer, where this model was validated and successfully applied in the general ICU. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to test this model on acute stroke patients who received tPA. The ability to identify LRM admissions can be used to support the development of intermediate care beds and step down units to care for LRM patients and to avoid the cost of constructing additional ICU beds, especially with scarcity of resources [10, 11].

Our study has several limitations. This is a single center study with a small number of patients, and this model may not apply to other neuroICUs; hence this would need to be studied in a large multicenter trial before it can be adopted for planning and management purposes. This model is thus not intended to triage individual admissions because it uses treatment and physiological data obtained during the first ICU day and not prior to ICU admission. For these reasons, ICU admission decisions for individuals still need to take into account physician judgment in addition to the characteristics of patient groups. In addition, the list in Table 1 does not include all possible treatments that might be required in a neuroICU, such as the need for assisted airway clearance which may be crucial in some stroke patients. ICU admission may be avoided, however, when services such as airway clearance, monitoring, and frequent neurochecks can be provided in non-ICU areas, such as intermediate care units.

Conclusion

The outcome of LRM patients in this study with ischemic stroke post-tPA suggests that they may not require admission to a formal neuroICU. Care of the LRM patients may be accomplished in an intermediate care unit, improving resource use and reducing costs. This model will need to be validated in other neuroICUs before it can be adopted.

Sponsorship

This study was not sponsored.

Funding

There was no funding used for this study.

Disclosures

None of the authors have anything to disclose.

| References | ▴Top |

- Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, Demchuk AM, Fugate JE, Grotta JC, Khalessi AA, et al. Scientific rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47(2):581-641.

doi pubmed - Chen LM, Kennedy EH, Sales A, Hofer TP. Use of health IT for higher-value critical care. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(7):594-597.

doi pubmed - Sinuff T, Kahnamoui K, Cook DJ, Luce JM, Levy MM, Values Ethics and Rationing in Critical Care Task Force. Rationing in Critical Care Task F. Rationing critical care beds: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1588-1597.

doi pubmed - Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA. A model for identifying patients who may not need intensive care unit admission. J Crit Care. 2010;25(2):205-213.

doi pubmed - Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, Malila FM. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today’s critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(5):1297-1310.

doi pubmed - Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Zimmerman JE, Bergner M, Bastos PG, Sirio CA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100(6):1619-1636.

doi pubmed - Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, Malila FM, Shaffer VL. Intensive care unit length of stay: Benchmarking based on Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(10):2517-2529.

doi pubmed - Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, Knaus WA, Williams JF, Kolakowski D, Draper EA. The use of risk predictions to identify candidates for intermediate care units. Implications for intensive care utilization and cost. Chest. 1995;108(2):490-499.

doi pubmed - Damiano AM, Bergner M, Draper EA, Knaus WA, Wagner DP. Reliability of a measure of severity of illness: acute physiology of chronic health evaluation—II. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(2):93-101.

doi - Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, Sun X, Knaus WA, Draper EA. Planning patient services for intermediate care units: insights based on care for intensive care unit low-risk monitor admissions. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(10):1626-1632.

doi pubmed - Junker C, Zimmerman JE, Alzola C, Draper EA, Wagner DP. A multicenter description of intermediate-care patients: comparison with ICU low-risk monitor patients. Chest. 2002;121(4):1253-1261.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.