| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Case Report

Volume 1, Number 2, June 2009, pages 109-114

Rapid Hemodynamic Deterioration and Death due to Acute Severe Refractory Septic Shock

Abhijeet Dhoblea, b, Won Chunga

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, USA

bCorresponding autor: Department of Internal Medicine, B 308 Clinical Center, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 48824-1313

Manuscript accepted for publication May 04, 2009

Short title: Severe Refractory Septic Shock

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jocmr2009.04.1238

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Despite emergence of early goal directed therapy, septic shock still carries a high mortality. Gram negative septicemia is notorious for rapid deterioration due to endotoxin release. Multi-organ damage due to septic shock carries poor prognosis, and such patients should be managed aggressively with multidisciplinary approach. We present a fatal case of a patient with gram negative septicemia who rapidly deteriorated, and died due to acute refractory severe septic shock. This patient probably developed urosepsis secondary to severe urinary tract infection. He also had infiltrates on chest radiograph. He expired within fifteen hours of presenting to the emergency department. This case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and management of septic shock. Early goal directed therapy has shown to improve mortality. Broad spectrum antibiotics should be started within one hour depending on local immunity of organisms. This case also highlights the fact that despite optimized treatment, this entity has very high mortality rates.

Keywords: Hemodynamic deterioration; Refractory septic shock; Gram negative septicemia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome which is characterized by severe infection leading to systemic inflammation and widespread cellular injury [1]. Similar systemic response also occurs in the absence of an infection. This entity is different from culture negative sepsis syndrome, in which case there is an evidence or suspicion of infection, but blood or body fluid cultures are negative [2, 3]. In fact, blood cultures are negative in 30 to 80 percent of patients with sepsis depending on the severity of syndrome [3].

Bloodstream infection is associated with high mortality rates. When bacteremia is associated with severe septic shock, gram negative and gram positive bacteria have comparable outcomes [4]. Dysregulation of anti and pro-inflammatory modulators is currently believed to be the center of pathogenesis of sepsis syndrome. Excessive spill of pro-inflammatory cytokines results in vasodilatation, increased endothelial permeability, leukocyte accumulation and neutrophils degranulation; leading to chain of events ensuing extensive tissue injury [5]. Cellular injury also plays an important role in the pathogenesis of sepsis through local hypoxia, apoptosis of injured cells, and direct cytotoxic effects [6]. Combination of excessive inflammation and cellular injury gives rise to full blown picture of sepsis syndrome (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Pathogenesis of sepsis |

EGDT has shown to increase survival by 20 % [10], and should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. This include invasive hemodynamic monitoring with the aim of maintaining: central venous pressure (CVP) between 8 and 12 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure 65 mm Hg, urine output 0.5 mL/kg/hr, and central venous or mixed venous oxygen (SvO2) saturation 70%. If the SvO2 is less than 70% after maintain CVP of 8-12 mm Hg, infusion of packed red blood cells is indicated to maintain hematocrit of at least 30%. Dobutamine infusion is also indicated if cardiac output is compromised [10, 20]. Appropriate cultures should be obtained before starting antibiotics.

Intravenous antibiotics should be started as early as possible and always within the first hour of recognizing severe sepsis and septic shock [20]. The site of infection and responsible microorganisms are usually not known initially in a patient with sepsis. Antibiotic treatment must be guided by the patients susceptibility group and local knowledge of bacterial resistance [21]. Intravenous broad spectrum antibiotics directed against both gram positive and gram negative bacteria should be administered immediately after appropriate cultures have been obtained. Few guidelines exist for the initial selection of empiric antibiotics. If pseudomonas is an unlikely pathogen, combination of vancomycin with either the third or fourth generation cephalosporin, or beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor, or carbapenem is an excellent initial choice. If pseudomonas is a possible pathogen, combination of vancomycin and two antipseudomonal agents should be considered. Antifungal agent may be considered initially if risk factors for fungal infection are present, or within 48 hours if no improvement occurs [21]. Antimicrobial regimen should be reassessed in 48-72 hours on the basis of microbiological and clinical data [22]. Antibiotics should be stopped if the cause is found to be non-infectious.

Intravenous hydrocortisone is indicated for adult septic shock when hypotension responds poorly to adequate fluid resuscitation and vasopressors. Hydrocortisone dose should be ≤ 300 mg/day. Steroids are not recommended to treat sepsis in the absence of shock unless the patients endocrine or corticosteroid history warrants it [23]. Recombinant human activated protein C should be considered in adult patients with sepsis-induced organ dysfunction with clinical assessment of high risk of death and if there are no contraindications [24].

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and management of septic shock. Gram negative septicemia is notorious for rapid deterioration due to endotoxin release. Multi-organ damage due to septic shock carries poor prognosis, and such patients should be managed aggressively with multidisciplinary approach. This case also highlights the fact that despite optimized treatment, this entity has very high mortality rates as shown in the previous studies. Nonetheless, early recognition, EGDT, and initiation of intravenous antibiotics are key components in treating patients with sepsis and septic shock.

Acknowledgments

The authors do not have any competing interests.

| References | ▴Top |

- Pinsky MR, Matuschak GM. Multiple systems organ failure: failure of host defense homeostasis. Crit Care Clin. 1989;5(2):199-220.

pubmed - Bone RC. Immunologic dissonance: a continuing evolution in our understanding of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(8):680-687.

pubmed - Brun-Buisson C, Doyon F, Carlet J. Bacteremia and severe sepsis in adults: a multicenter prospective survey in ICUs and wards of 24 hospitals. French Bacteremia-Sepsis Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:617-624.

pubmed - Miller PJ, Wenzel RP. Etiologic organisms as independent predictors of death and morbidity associated with bloodstream infections. J Infect Dis. 1987;156(3):471-477.

pubmed - Pruitt JH, Copeland EM, 3rd, Moldawer LL. Interleukin-1 and interleukin-1 antagonism in sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and septic shock. Shock. 1995;3(4):235-251.

pubmed - Bone RC. The pathogenesis of sepsis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(6):457-469.

pubmed - Movat HZ, Cybulsky MI, Colditz IG, Chan MK, Dinarello CA. Acute inflammation in gram-negative infection: endotoxin, interleukin 1, tumor necrosis factor, and neutrophils. Fed Proc. 1987;46(1):97-104.

pubmed - Zeni F, Freeman B, Natanson C. Anti-inflammatory therapies to treat sepsis and septic shock: a reassessment. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(7):1095-1100.

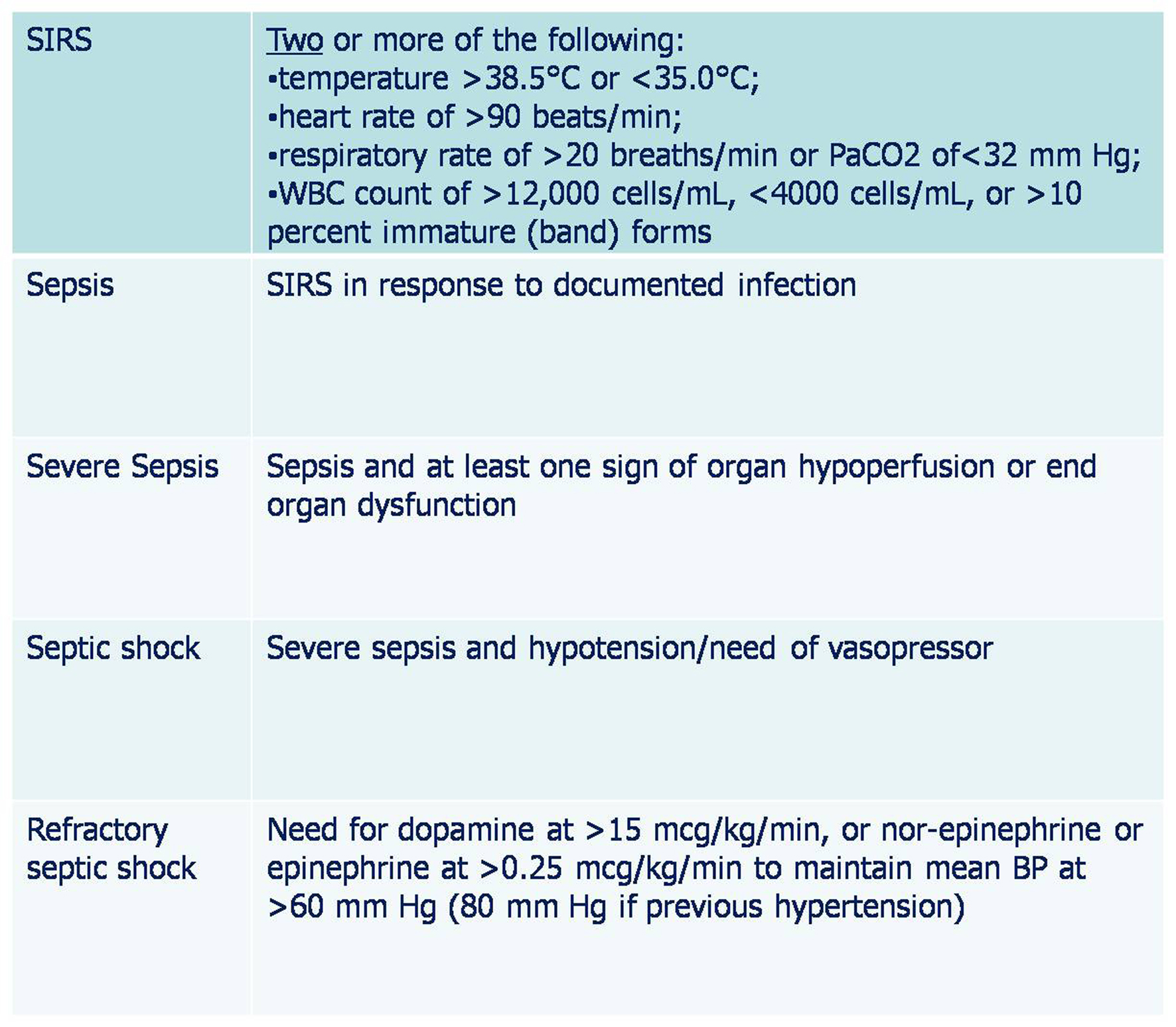

pubmed - Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, Hwang T, Davis CS, Wenzel RP. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA. 1995;273(2):117-123.

pubmed - Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E,

et al . Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368-1377.

pubmed - O'Brien JM, Jr . , Ali NA, Aberegg SK, Abraham E. Sepsis. Am J Med. 2007;120(12):1012-1022.

pubmed - Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546-1554.

pubmed - Dombrovskiy VY, Martin AA, Sunderram J, Paz HL. Rapid increase in hospitalization and mortality rates for severe sepsis in the United States: a trend analysis from 1993 to 2003. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1244-1250.

pubmed - Esper A, Martin GS. Is severe sepsis increasing in incidence AND severity? Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1414-1415.

pubmed - Dombrovskiy VY, Martin AA, Sunderram J, Paz HL. Facing the challenge: decreasing case fatality rates in severe sepsis despite increasing hospitalizations. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(11):2555-2562.

pubmed - Gaynes R, Edwards JR, National Nosocomial. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(6):848-854.

pubmed - Lever A, Mackenzie I. Sepsis: definition, epidemiology, and diagnosis. BMJ. 2007;335(7625):879-883.

pubmed - Suarez CJ, Lolans K, Villegas MV, Quinn JP. Mechanisms of resistance to beta-lactams in some common Gram-negative bacteria causing nosocomial infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2005;3(6):915-922.

pubmed - Graff LR, Franklin KK, Witt L, Cohen N, Jacobs RA, Tompkins L, Guglielmo BJ. Antimicrobial therapy of gram-negative bacteremia at two university-affiliated medical centers. Am J Med. 2002;112(3):204-211.

pubmed - Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K,

et al . Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(1):296-327.

pubmed - Mackenzie I, Andrew L. Management of sepsis. BMJ. 2007;335(7626):929-932.

pubmed - Bochud PY, Bonten M, Marchetti O, Calandra T. Antimicrobial therapy for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:S495-S512.

pubmed - Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, Bollaert PE, François B, Korach JM, Capellier G,

et al . Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288(7):862-871.

pubmed - Abraham E, Laterre PF, Garg R, Levy H, Talwar D, Trzaskoma BL, Francois B,

et al . Administration of Drotrecogin Alfa (Activated) in Early Stage Severe Sepsis (ADDRESS) Study Group Drotrecogin alfa (activated) for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(13):1332-1341.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.