| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jocmr.org |

Review

Volume 14, Number 2, February 2022, pages 88-94

A Literature Review of Factors Related to Postoperative Sore Throat

Yuta Mitobea, h, Yuri Yamaguchib, Yasuko Babac, Tomomi Yoshiokad, Kenji Nakagawae, Takeshi Itouf, Kiyoyasu Kurahashig

aGraduate School of Health and Welfare Science, International University of Health and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan

bDepartment of Anesthesiology, Yokohama Municipal Citizen’s Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan

cDepartment of Anesthesiology, International University of Health and Welfare, Mita Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

dDepartment of Nursing, Faculty of Health Science, Tokoha University, Shizuoka, Japan

eDepartment of Nursing, International University of Health and Welfare, Mita Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

fDepartment of Nursing, Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

gDepartment of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care Medicine, International University of Health and Welfare, Chiba, Japan

hCorresponding Author: Yuta Mitobe, Graduate School of Health and Welfare Science, International University of Health and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan

Manuscript submitted January 14, 2022, accepted February 8, 2022, published online February 24, 2022

Short title: Factors Related to Postoperative Sore Throat

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr4665

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Postoperative sore throat can occur as a complication in patients who have undergone surgery under general anesthesia. The incidence of postoperative sore throat ranges from 12.1% to 70%, and its effects include damage to the epithelium and mucosal cells caused by airway securement, damage to the vocal cords, congestion, blood clots, and factors such as an inappropriately large tube, cuff shape, cuff pressure, and airway securement. Notably, there are individual differences in pain thresholds, and the sensation of pain is affected by mental states, such as anxiety, and varies from person to person. Therefore, we conducted a literature review using PubMed to clarify patient factors related to the development of postoperative sore throat. The extracted keywords were “postoperative sore throat,” “anesthesia,” and “patient factors.” We found 16 articles that met our search criteria. We expanded the search period and retrieved 19 cases from 1990 to 2020. We also included references that were judged to be closely related to the list of citations of the retrieved references. The study designs included were randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, meta-analyses, reviews, and systematic reviews. The results showed that female sex, smoking, and age were the most common patient factors. However, we could not find any literature that studied the relationship between postoperative sore throat and mental states such as anxiety.

Keywords: Postoperative sore throat; Anesthesia; Patient factors

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Postoperative sore throat (POST) is one of the most common postoperative complications. The incidence of POST ranges from 12.1% to 70% [1-3]. POST has been shown to decrease postanesthesia recovery and inpatient satisfaction [4]. In addition, POST can cause aspiration pneumonia [5-7]. The mechanisms of POST include damage to the epithelium and mucosal cells due to airway secretion, damage to the vocal cords, and congestive blood loss [8]. In recent years, research has been conducted on the factors that cause POST; and it has been reported that the shape of intubation tubes [6, 9], cuffs size [10], endotracheal intubation technique [8], cuff pressure [11, 12], and use of inhalation anesthesia [13] are among such factors. In addition, the efficacy of topical dexamethasone [7] and magnesium [14] as POST prophylaxis, as well as the ineffectiveness of lidocaine spray [15, 16], have been demonstrated. Complications were scored preoperatively to predict postoperative complications. For example, for postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), Apfel et al [17] scored the preoperative risk. However, no study has scored the preoperative risk factors for POST. Notably, pain as a sensation is related to attributes such as time, space, pressure, and temperature, and the emotional nature of pain as a sensation, including tension and fear, has been described. Furthermore, when confronted with pain, if we want to evaluate the organic cause of the pain, we must exclude pain as an emotion to evaluate it; however, if the pain is strong despite little organic damage, we may have to focus on pain as an emotion. In pain assessment, it is often useful to divide pain into sensory and emotional pain. Therefore, we focused on the tension and anxiety of patients in response to POST and reviewed the literature to determine whether POST has an emotional nature, but we could not find any relevant studies [18]. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to systematically collect and integrate information through a review to clarify the patient factors associated with POST.

| Research Methods | ▴Top |

Literature review methods

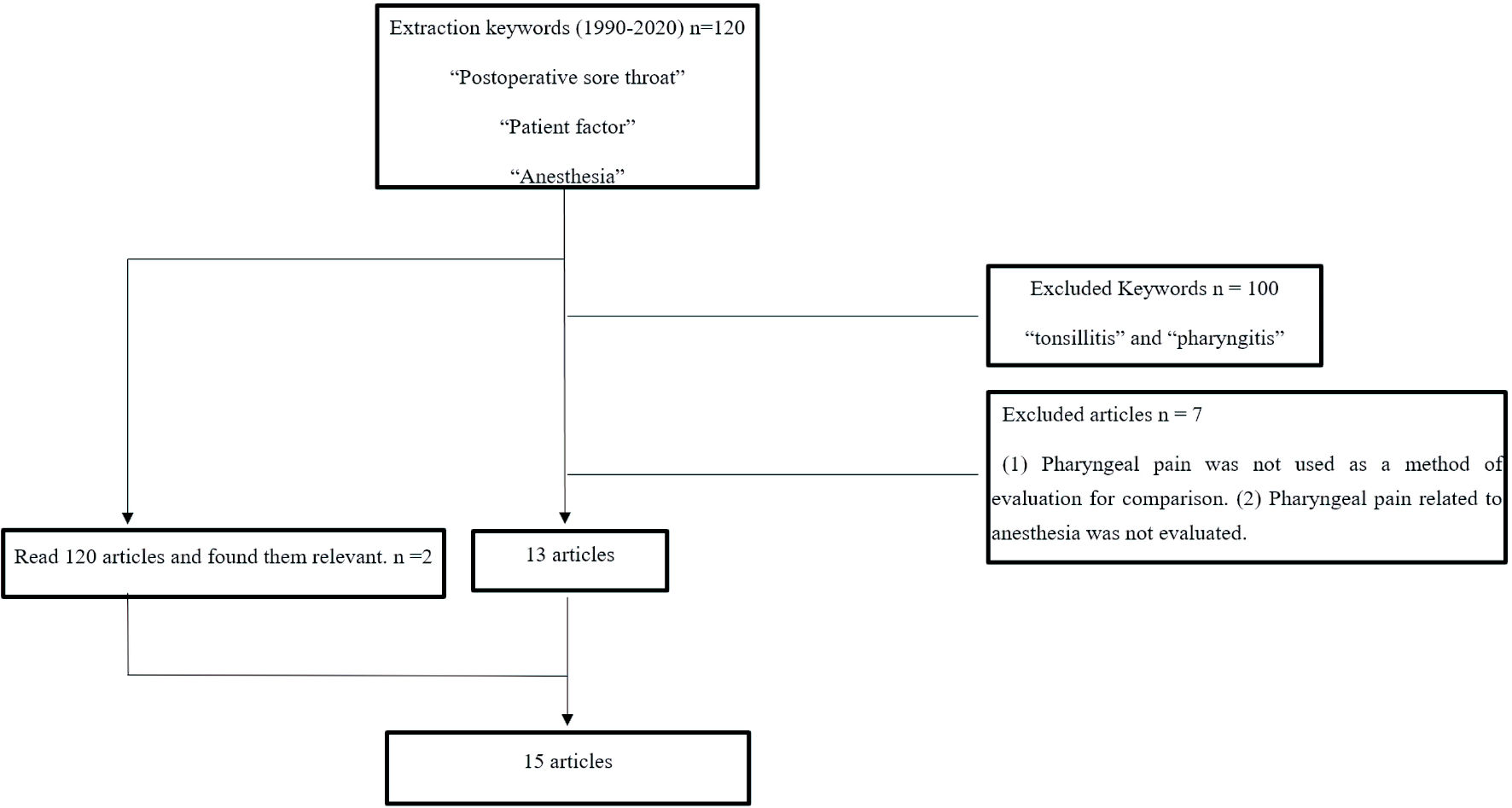

We searched PubMed for articles on patient factors associated with POST. For PubMed, the literature extraction period was 2010 - 2020, and the extraction keywords were “postoperative sore throat,” “anesthesia,” and “patient factors.” We excluded patients with “tonsillitis” and “pharyngitis” from our search. We expanded the search period and retrieved 19 cases from April 1990 to March 2020. Because there were not enough papers and cases, we also included references that were judged to be closely related to the list of citations of the retrieved references. The study designs included were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), clinical trials, meta-analyses, reviews, and systematic reviews.

Literature review methods

The titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine if they described sore throat as a complication of surgical anesthesia. Finally, 15 articles that met the following criteria were selected for analysis: 1) studies investigating factors associated with PONV; and 2) those in which pharyngeal pain related to anesthesia was evaluated.

| Results | ▴Top |

Literature analysis

A total of 120 articles were identified using the keyword search. Of these, 20 were RCTs, clinical trials, meta-analyses, reviews, and systematic reviews with human subjects in the study design. Then, seven articles were excluded based on the exclusion criteria, leaving 13 articles that met all the criteria. Finally, two hand-searched articles were added to create a total of 15 articles in this study (Fig. 1). The common patient characteristics in the literature were American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grades I - III in adults, height, weight, and sex. There were 10 device factors for securing the airway, and five of them had significant differences in sore throat. Among them, “tube insertion time” was extracted as a factor in four articles. Among the articles that showed significant factors associated with a sore throat, “age” was extracted as a factor in two articles, and “female” and “smoking history” were also extracted in two articles (Table 1 [2, 19-32]).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Flowchart of literature review. |

Click to view | Table 1. Studies Included in the Analysis |

Relationship between anesthesia techniques and POST

Regarding the relationship between anesthesia technique and POST, the incidence of POST associated with different types of airway management tubes, cuff pressures, and cuff contents has been reported. In nine articles, the incidence of POST was associated with different types of airway management tubes. Depending on the type of airway management tube, the average time to successful airway clearance ranged from 12 to 60 s, and the incidence of POST ranged from 6.8% to 50% [19-26, 33] (Table 2 [19-24, 30]). Two articles examined the incidence of POST associated with differences in cuff pressure and cuff contents (Table 3) [27, 28].

Click to view | Table 2. Relationship Between Anesthesia Techniques and Postoperative Sore Throat |

Click to view | Table 3. Relationship Between Cuff Pressure and Postoperative Sore Throat |

Association between POST and characteristics of patients undergoing surgery

Regarding the relationship between POST and characteristics of patients undergoing surgery, the incidence of POST according to sex and age, according to the ASA preoperative status classification (ASA physical status), and due to previous respiratory disease and smoking have been reported. Biro et al [29] evaluated the incidence of POST by using a visual analog scale at 12 to 24 h postoperatively and found that 40% of the patients had POST. There were significant differences in age, sex, presence of airway or lung disease, smoking history, pharyngeal temperature sensor, PONV, and anesthesia duration. Logistic analysis revealed seven significant factors: female sex, bloodstains on the intubation tube after extubation, use of dentures, history of respiratory disease, young age, PONV, and anesthesia duration. Higgins et al [1, 2] evaluated the incidence of POST in the postanesthesia care unit 24 h postoperatively in the tracheal intubation, laryngeal mask airway (LMA), and facemask (FM) groups. The incidence of POST was higher in the endotracheal tube (ETT) group (45.5%), followed by the LMA group (17.5%) and FM group (3.3%). Predictors of POST included female sex, age (mean 47 years), current smoker status, ASA, and gynecological and ophthalmic surgery (Table 4 [2, 29]).

Click to view | Table 4. Predictors of Postoperative Sore Throat |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this study, we reviewed patient factors related to POST. Most of the studies we identified were concerned with devices and anesthesia techniques for securing the airway, but there were also some references to patient factors.

Relationship between anesthesia techniques and POST

The results of the present study reveal that the devices and procedures necessary for securing the airway can cause POST [19-21, 24, 25, 30]. Physical agents such as tubes irritate the airway during intubation and surgery, causing sore throat [34, 35]. The cuff of the tube, dryness of the mucosa, and abrasion of the airway mucosa during intubation, caused by the rubbing of the intubation tube against the airway mucosa, are thought to be the etiological factors of POST. In addition, the damage to the airway mucosa caused by the strong stimulation by the laryngoscope and the movement of the intubation tube excites the C fibers related to secondary pain, and the subsequent release of neurotransmitters is related to POST. El-Boghdadly et al [3] also cited blood contamination of the tube after removal as a risk factor for sore throat. Therefore, we believe that the persistence of physical irritation from intubation to the completion of surgery may cause POST. To address this, we believe that minimizing physical stimulation, for example, choosing a device that takes into account the operative time and intubation as well as extubation techniques, can help prevent the risk of sore throat. The insertion time of the tube was also mentioned as a factor in these studies [19-21, 24, 29]. Hsu et al [36] found that the shorter the time to secure the airway, the lower the incidence of POST in their study using a video laryngoscope to insert a double-lumen endotracheal tube into the correct position. Hence, a short time to airway clearance can minimize the invasion of the airway mucosa [24, 30]. This may have been a factor causing POST in much of the current literature. There was a difference in the incidence of POST depending on the shape and nature of the device used to secure the trachea. However, we were not able to clarify the relationship between the number of risk factors (number of physical stimuli and procedural factors) and the occurrence of POST as well as the severity and duration of POST.

Association between preoperative factors and POST

The patient factors were “smoking history,” “female sex,” and “age.” The relationship between smoking and respiratory diseases has been clarified in many studies [37, 38]. The mechanism is generally known to be inflammation of the bronchi and alveoli and eventual destruction of the alveoli. As reported by Tanaka et al [1] and Piriyapatsom et al [39], POST is thought to be triggered by material stimuli (device factors) to the airways where chronic inflammation occurs, causing abrasion of the airway mucosa and release of neurotransmitters. Pain, on the other hand, is a sensation felt when one’s own body is injured and is subjective. Anxiety and psychological stress have been reported to increase pain [40], and the threshold of pain varies from person to person. Feine et al [41] stated that when men and women are given the same pain stimulus, women evaluate the degree of pain more strongly. Lautenbacher et al [42] measured pain tolerance thresholds and found that men tended to have higher thresholds than women. This suggests that “women” became a factor influencing POST by recognizing and expressing POST. However, Jaensson et al [25] did not find any significant difference in the occurrence of POST between men and women, suggesting that POST is more likely to occur when several factors overlap. As for age, “young age” has been cited as a factor associated with POST. The experimental pressure pain detection thresholds showed that the intensity and unpleasantness of the pain stimulus were significantly rated lower in the older than in the younger patient population [43]. After investigating changes in pain perception, Lautenbacher et al [44] also found that aging decreases pain sensitivity and intensity. These findings suggest that age is a factor in POST.

Limitations

In this study, we conducted a literature review to clarify patient factors associated with the occurrence of POST. We found factors related to the anesthesia technique and patients, but these factors were not independent of each other and worked in combination to cause POST. However, it was not clear how many of these factors worked in combination to cause POST and whether the combination of factors affected the severity and duration of POST. In addition, since pain is related to both sensory and emotional aspects, it was not clear whether the emotional aspect was a factor causing POST or whether it affected the severity and duration. The present review did not find any reports related to POST or emotional factors. Therefore, there is a need for further research on POST and psychological factors.

| Conclusions | ▴Top |

In this study, we reviewed the literature and examined the factors contributing to POST. Besides the most common patient factors like woman, smoking, and age, this study found that POST may be associated with mental states such as anxiety.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant (number: JP1919577).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

YY designed the study. KN, TI, and TY participated in data acquisition, extraction, and analysis, and drafted the final work. KK and YB supervised this manuscript’s preparation and writing. The authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript and approved it for publication.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Tanaka Y, Nakayama T, Nishimori M, Sato Y, Furuya H. Lidocaine for preventing postoperative sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD004081.

doi - Higgins PP, Chung F, Mezei G. Postoperative sore throat after ambulatory surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88(4):582-584.

doi pubmed - El-Boghdadly K, Bailey CR, Wiles MD. Postoperative sore throat: a systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2016;71(6):706-717.

doi pubmed - Lehmann M, Monte K, Barach P, Kindler CH. Postoperative patient complaints: a prospective interview study of 12,276 patients. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(1):13-21.

doi pubmed - Liang Gong-Meng. A case of prolonged sore throat and dysphagia after Laryngeal tube surgery. Saiseikai Senri Hospital Medical Journal. 2006;16(1):20-22.

- Saeki H, Morimoto Y, Yamashita A, Nagusa Y, Shimizu K, Oka H, Miyauchi Y. [Postoperative sore throat and intracuff pressure: comparison among endotracheal intubation, laryngeal mask airway and cuffed oropharyngeal airway]. Masui. 1999;48(12):1328-1331.

- Lee J, Park HP, Jeong MH, Kim HC. Combined intraoperative paracetamol and preoperative dexamethasone reduces postoperative sore throat: a prospective randomized study. J Anesth. 2017;31(6):869-877.

doi pubmed - Winkel E, Knudsen J. Effect on the incidence of postoperative sore throat of 1 percent cinchocaine jelly for endotracheal intubation. Anesth Analg. 1971;50(1):92-94.

doi pubmed - Hu B, Bao R, Wang X, Liu S, Tao T, Xie Q, Yu X, et al. The size of endotracheal tube and sore throat after surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e74467.

doi pubmed - Chang JE, Kim H, Han SH, Lee JM, Ji S, Hwang JY. Effect of Endotracheal Tube Cuff Shape on Postoperative Sore Throat After Endotracheal Intubation. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(4):1240-1245.

doi pubmed - Sato K, Tanaka M, Nishikawa T. [Changes in intracuff pressure of endotracheal tubes permeable or resistant to nitrous oxide and incidence of postoperative sore throat]. Masui. 2004;53(7):767-771.

- Joe HB, Kim DH, Chae YJ, Kim JY, Kang M, Park KS. The effect of cuff pressure on postoperative sore throat after Cobra perilaryngeal airway. J Anesth. 2012;26(2):225-229.

doi pubmed - Park JH, Lee YC, Lee J, Kim S, Kim HC. Influence of intraoperative sevoflurane or desflurane on postoperative sore throat: a prospective randomized study. J Anesth. 2019;33(2):209-215.

doi pubmed - Flexman AM, Duggan LV. Postoperative sore throat: inevitable side effect or preventable nuisance? Can J Anaesth. 2019;66(9):1009-1013.

doi pubmed - Loeser EA, Kaminsky A, Diaz A, Stanley TH, Pace NL. The influence of endotracheal tube cuff design and cuff lubrication on postoperative sore throat. Anesthesiology. 1983;58(4):376-379.

doi pubmed - Estebe JP, Delahaye S, Le Corre P, Dollo G, Le Naoures A, Chevanne F, Ecoffey C. Alkalinization of intra-cuff lidocaine and use of gel lubrication protect against tracheal tube-induced emergence phenomena. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92(3):361-366.

doi pubmed - Apfel CC, Heidrich FM, Jukar-Rao S, Jalota L, Hornuss C, Whelan RP, Zhang K, et al. Evidence-based analysis of risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(5):742-753.

doi pubmed - Akamatsu M. Pain and evaluation. Journal of the Biomechanical Society of Japan. 1990;14(3):151-159.

- Chen MK, Hsu HT, Lu IC, Shih CK, Shen YC, Tseng KY, Cheng KI. Techniques for the insertion of the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway: comparison of the Foley airway stylet tool with the introducer tool in a prospective, randomized study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;14:105.

doi pubmed - Tan MG, Chin ER, Kong CS, Chan YH, Ip-Yam PC. Comparison of the re-usable LMA Classic and two single-use laryngeal masks (LMA Unique and SoftSeal) in airway management by novice personnel. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2005;33(6):739-743.

doi pubmed - Bein B, Worthmann F, Scholz J, Brinkmann F, Tonner PH, Steinfath M, Dorges V. A comparison of the intubating laryngeal mask airway and the Bonfils intubation fibrescope in patients with predicted difficult airways. Anaesthesia. 2004;59(7):668-674.

doi pubmed - Andrews DT, Williams DL, Alexander KD, Lie Y. Randomised comparison of the Classic Laryngeal Mask Airway with the Cobra Perilaryngeal Airway during anaesthesia in spontaneously breathing adult patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37(1):85-92.

doi pubmed - Kihara S, Watanabe S, Taguchi N, Suga A, Brimacombe JR. A comparison of blind and lightwand-guided tracheal intubation through the intubating laryngeal mask. Anaesthesia. 2000;55(5):427-431.

doi pubmed - Shariffuddin, II, Teoh WH, Tang E, Hashim N, Loh PS. Ambu(R) AuraGain versus LMA Supreme Second Seal: a randomised controlled trial comparing oropharyngeal leak pressures and gastric drain functionality in spontaneously breathing patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2017;45(2):244-250.

doi pubmed - Jaensson M, Gupta A, Nilsson U. Gender differences in sore throat and hoarseness following endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask airway: a prospective study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;14:56.

doi pubmed - Griffiths JD, Nguyen M, Lau H, Grant S, Williams DI. A prospective randomised comparison of the LMA ProSeal versus endotracheal tube on the severity of postoperative pain following gynaecological laparoscopy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2013;41(1):46-50.

doi pubmed - Amini A, Zand F, Sadeghi SE. A comparison of the disposable vs the reusable laryngeal tube in paralysed adult patients. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(11):1167-1170.

doi pubmed - Bennett MH, Isert PR, Cumming RG. Postoperative sore throat and hoarseness following tracheal intubation using air or saline to inflate the cuff—a randomized controlled trial. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28(4):408-413.

doi pubmed - Biro P, Seifert B, Pasch T. Complaints of sore throat after tracheal intubation: a prospective evaluation. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2005;22(4):307-311.

doi pubmed - Teoh WH, Shah MK, Sia AT. Randomised comparison of Pentax AirwayScope and Glidescope for tracheal intubation in patients with normal airway anatomy. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(10):1125-1129.

doi pubmed - Lomax SL, Johnston KD, Marfin AG, Yentis SM, Kathawaroo S, Popat MT. Nasotracheal fibreoptic intubation: a randomised controlled trial comparing the GlideRite(R) (Parker-Flex(R) Tip) nasal tracheal tube with a standard pre-rotated nasal RAE tracheal tube. Anaesthesia. 2011;66(3):180-184.

doi pubmed - Schaefer HG, Marsch SC, Keller HL, Strebel S, Anselmi L, Drewe J. Teaching fibreoptic intubation in anaesthetised patients. Anaesthesia. 1994;49(4):331-334.

doi pubmed - Teoh WH, Lim Y. Comparison of the single use and reusable intubating laryngeal mask airway. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(4):381-384.

doi pubmed - Cui Y, Liu KWK, Ip MSM, Liang Y, Mak JCW. Protective effect of selegiline on cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in rat lungs in vivo. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(21):1418.

doi pubmed - Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1341-1351.

doi - Hsu HT, Chou SH, Chou CY, Tseng KY, Kuo YW, Chen MC, Cheng KI. A modified technique to improve the outcome of intubation with a left-sided double-lumen endobronchial tube. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;14:72.

doi pubmed - Jayes L, Haslam PL, Gratziou CG, Powell P, Britton J, Vardavas C, Jimenez-Ruiz C, et al. SmokeHaz: systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the effects of smoking on respiratory health. Chest. 2016;150(1):164-179.

doi pubmed - Thomson NC. Asthma and smoking-induced airway disease without spirometric COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5):1602061.

doi pubmed - Piriyapatsom A, Dej-Arkom S, Chinachoti T, Rakkarnngan J, Srishewachart P. Postoperative sore throat: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96(8):936-942.

- Ali A, Altun D, Oguz BH, Ilhan M, Demircan F, Koltka K. The effect of preoperative anxiety on postoperative analgesia and anesthesia recovery in patients undergoing laparascopic cholecystectomy. J Anesth. 2014;28(2):222-227.

doi pubmed - Feine JS, Bushnell CM, Miron D, Duncan GH. Sex differences in the perception of noxious heat stimuli. Pain. 1991;44(3):255-262.

doi - Lautenbacher S, Strian F. Sex differences in pain and thermal sensitivity: the role of body size. Percept Psychophys. 1991;50(2):179-183.

doi pubmed - Petrini L, Matthiesen ST, Arendt-Nielsen L. The effect of age and gender on pressure pain thresholds and suprathreshold stimuli. Perception. 2015;44(5):587-596.

doi pubmed - Lautenbacher S, Peters JH, Heesen M, Scheel J, Kunz M. Age changes in pain perception: A systematic-review and meta-analysis of age effects on pain and tolerance thresholds. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;75:104-113.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.