| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jocmr.org |

Review

Volume 13, Number 9, September 2021, pages 460-465

Incidence of Extrahepatic Portal Vein Anatomic Variations and Their Clinical Implications in Daily Practice

Anastasios Katsourakisa, e , Dimitrios Chytasb, Eva Filoa, Iosif Chatzisa, Pantelis Chouridisc, Georgios Komsisd, George Noussiosd

aDepartment of General Surgery, Agios Dimitrios General Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece

bDepartment of Physiotherapy, University of Peloponnese, Sparta, Greece

cENT Police Medical Centre, Thessaloniki, Greece

dDepartment of Physical Education and Sports Sciences at Serres, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

eCorresponding Author: Anastasios Katsourakis, Department of General Surgery, Agios Dimitrios General Hospital, ElenisZografou 2, 54634 Thessaloniki, Greece

Manuscript submitted August 20, 2021, accepted September 2, 2021, published online September 30, 2021

Short title: Portal Vein Anatomic Variations

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr4581

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Anatomical variations of the portal vein are relatively common and can affect the outcomes of hepatic resections, transplantations and interventional radiological procedures. The aim of this study was to review the literature regarding extrahepatic portal vein anomalies. Two main databases were searched for suitable articles, and results concerning more than 3,700 patients were included in the analysis. The most common anatomical variations of the portal vein were trifurcation and having a right posterior portal vein as the first branch of the main portal vein; these anomalies were found in 11.7% and 10.8% of cases, respectively.

Keywords: Portal vein; Anatomic variation; Portal system; Clinical practice

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The portal vein (PV), also known as the “vena portae”, is the main vessel that transfers blood from the digestive system and spleen to the liver. The PV is formed by the junction of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins, and it supplies about 75% of the liver’s blood, with the rest coming from the hepatic artery proper. The PV is not a true vein because it does not conduct blood directly to the heart. Anatomical variations of the PV are not unusual, with the reported incidence of PV variations in the range of 0.1-25% [1-4]. Yet, these variations may not be uncovered but until a complex hepatobiliary surgical procedure or vascular intervention is undertaken; lately, the use of such procedures has increased because of medical and technological advancements [5-8]. The purpose of this study was to review the literature and determine the types and incidence of variant extrahepatic PV anatomy.

| Methods | ▴Top |

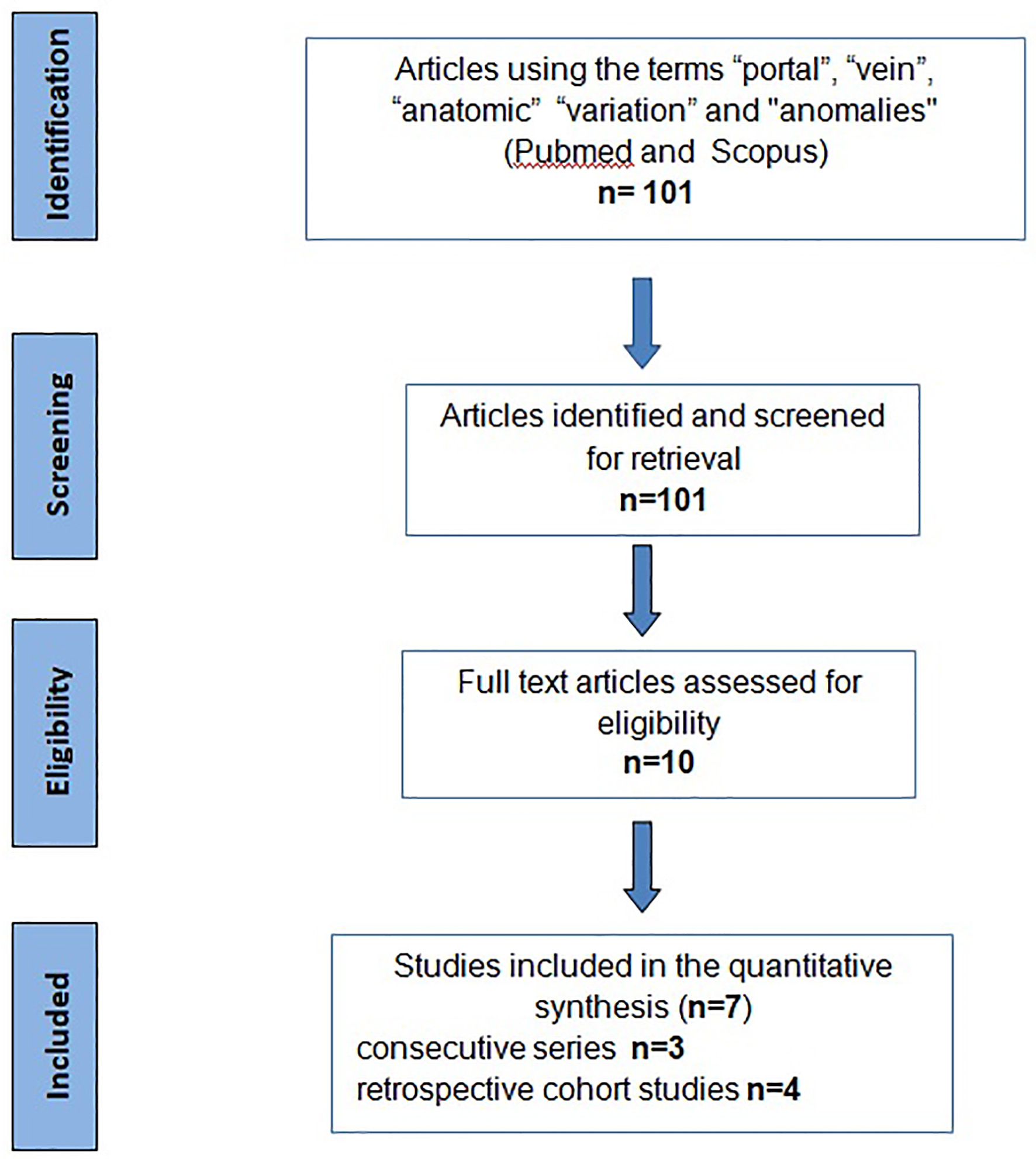

A systematic search of the scientific literature was carried out using the PubMed and Scopus databases for the years 2002 - 2021 to obtain access to all publications describing anatomic variations of the extrahepatic PV. The following terms and their combinations were used: “portal”, “vein”, “anatomic”, “anomalies”, and “variations”. The references of all the articles that were considered relevant were checked to find any studies missed. The criteria for inclusion of data in the study were as follows: 1) the study had to be an original article or a review; 2) only studies concerning adult humans were selected; and 3) only articles written in English were used. The following exclusion criteria were used for this study: 1) articles concerning populations overlapping one another were excluded; 2) populations overlapping with other groups; and 3) articles that reported case reports, conference abstracts, letters to the editor and small case series were removed from the sample. We only considered studies from the field of radiology because of the large number of patients they include, with more than 20 patients participating in each study. No review protocol existed. The analysis was performed according to the preferred reporting items for systemic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and conducted by two separate reviewers, who were responsible for the data extraction.

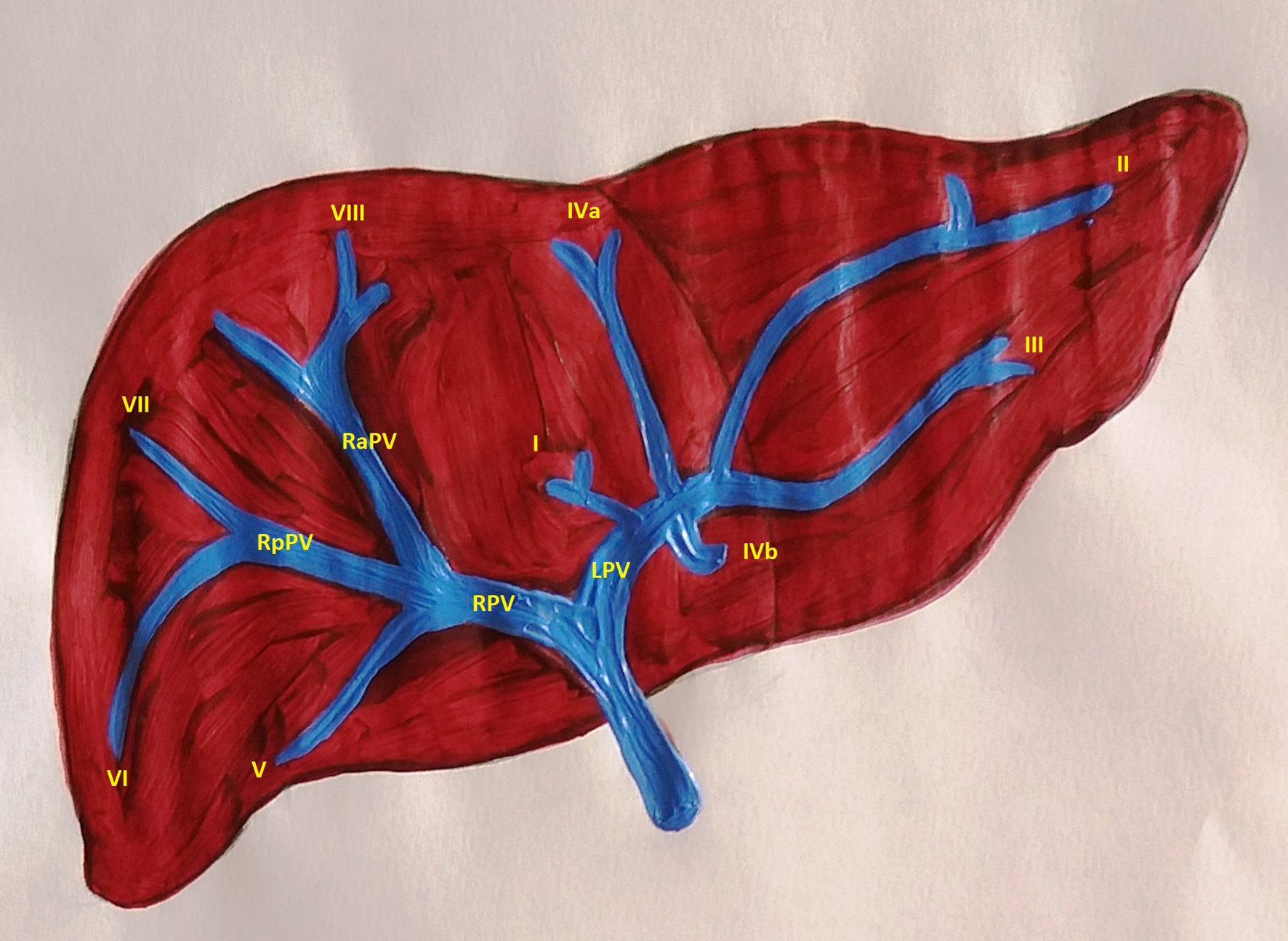

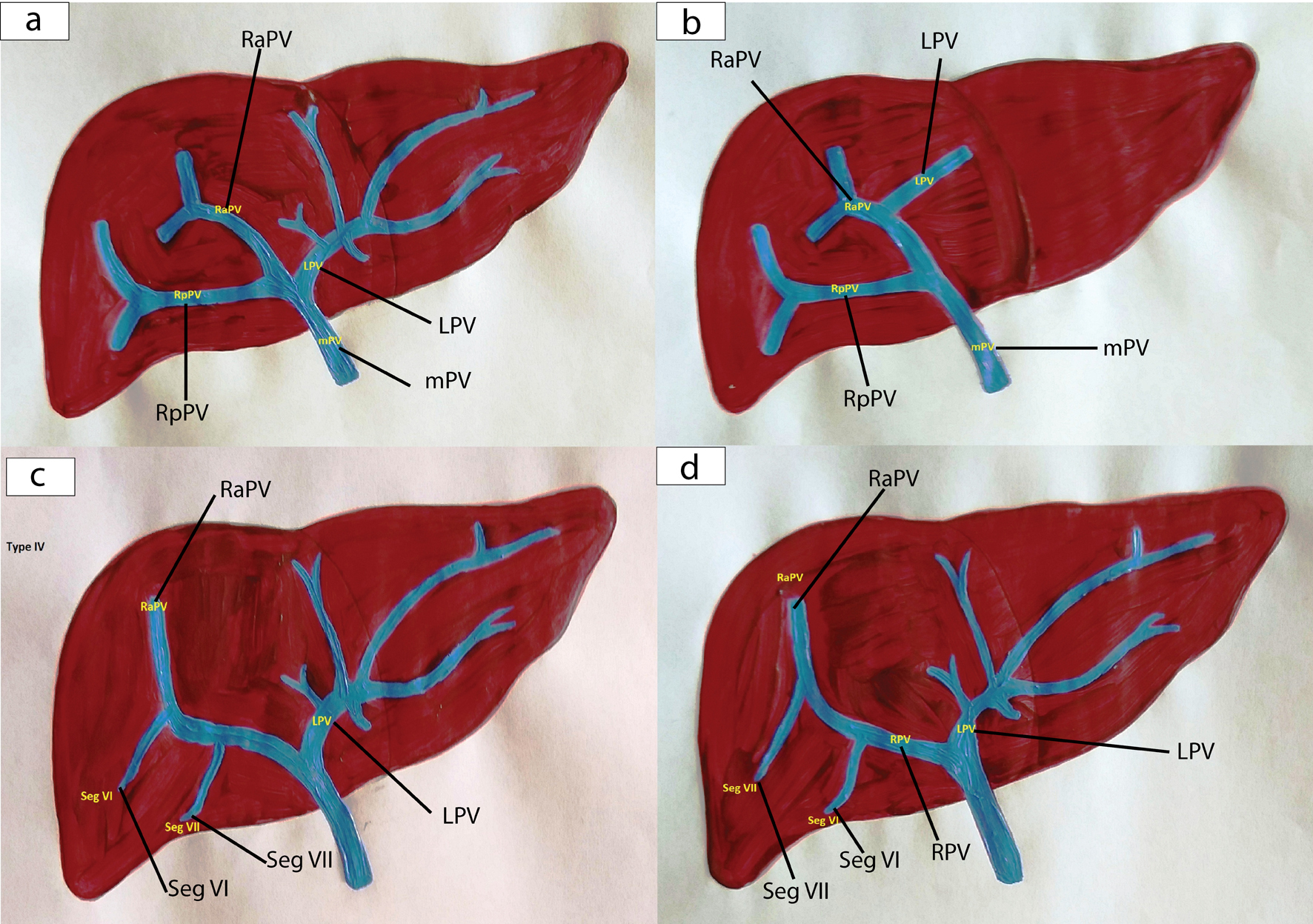

We use the five types of PV anatomic variations as classified by Covey (Table 1; Figs. 1 and 2). We review only extrahepatic variations of the PV. For each study considered eligible, the year of publication and the type of study have been investigated.

Click to view | Table 1. Common PV Variations as Classified by Covey |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Normal anatomy of the portal system (type I). RPV: right portal vein; LPV: left portal vein; RaPV: right anterior portal vein; RpPV: right posterior portal vein. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Anatomical variations of the portal vein (a: type II; b: type III; c: type IV; d: type V). RPV: right portal vein; LPV: left portal vein; mPV: main portal vein; RaPV: right anterior portal vein; RpPV: right posterior portal vein. |

| Results | ▴Top |

An initial search of the databases identified a total of 101 records; 91 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. Ten articles were assessed for eligibility, of these three were excluded due to incomplete data, and finally seven articles were used in the quantitative analysis (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Flow diagram according to PRISMA guidelines. PRISMA: preferred reporting items for systematic reviews. |

A total of 3,715 patients were included in our study (Table 2) [9-15]. A conventional branch pattern (type I) was identified in 2,795 of 3,715 patients (75.2%). The pattern of trifurcation (type II) was identified in 356 patients (9.6%), while right posterior PV (RpPV) as the first branch of the main PV, which is a type III variant, was present in 306 patients (8.2%). Type IV variants involving a separate origin of segment VII from the right portal vein (RPV) and type V which involves a different origin of segment VI from the RPV were present in 49 patients (1.1%) and 33 patients (0.9%), respectively (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 2. Classification of the Articles According to the Number of Patients and Type of Study |

Click to view | Table 3. Distribution of the Found Anatomic Variations of Portal Vein |

The least common variations were the right anterior portal vein (RaPV) originating from the left PV (LPV), trifurcation of the RPV, absence of PV bifurcation, total ramification and left PV originating from the RaPV (Table 3).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Liver interventions are becoming more complex and demanding, resulting in increased awareness of normal and variant anatomy, where the variance mainly relates to the vessels. This complexity has been noticed in the liver transplantation and hepatic resection literature. Many surgeons routinely perform preoperative computed tomography to check for replaced or accessory vessels; therefore, a thorough understanding of variants in PV is crucial [4, 7, 16].

Embryologically, the PV is formed from the fourth to fifth weeks of gestation. Initially, there are three paired venous systems, which are as follows: the umbilical veins of chorionic origin, the vitelline veins from the yolk sac and the cardinal veins. Anastomosis is formed between the right and left vitelline veins. Involution of the vitelline veins results in the formation of the PV. The stem of the PV is formed by the left vitelline vein, the left branch from part of the left vitelline vein and the right branch from part of the right vitelline vein. Any diversion from this development results in anomalies of the PV [17, 18].

Anatomically, the PV supplies the liver with more than 70% of its total oxygen, and the normal pressure is 7 mm Hg. The PV is formed by the junction of the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein behind the pancreatic head at the level of the second lumbar vertebra. At the hilum, the main PV splits into the left and right PVs. The RPV is then divided into the RaPV and RpPV. The RaPV supplies segments V and VIII, while the RpPV supplies segments VI and VII. The LPV gives branches to segments II, III and IV and the caudate lobe [19-21].

From the studies included in our analysis, only Bayrak et al [15] categorized patients by sex, but no statistically significant difference was detected in PV variations between the male and female participants. Regarding race-related differences, Munguti et al [22] concluded that extrahepatic termination of the PV is more common in the Asian population followed by the American and then the African populations, which suggests that the later are more vulnerable to injury during surgery and radiological interventions.

More rare anatomic variations of the PV can be related to other abnormalities. An example of such variations is preduodenal PV, where the PV lies anterior to the duodenum. Preduodenal PV is associated with intestinal obstruction, biliary atresia, annular pancreas and situs inversus. Absence of the PV can be linked to other anomalies, such as cardiac defects, skeletal anomalies, situs inversus, polysplenia and liver pathology, while PV atresia or stenosis can cause obstruction accompanying portal hypertension, splenomegaly and gastrointestinal hemorrhage known as Banti syndrome [23, 24]. In most of PV variations, the laboratory tests to evaluate liver function are typically normal. The values of liver enzymes and bilirubin and clotting times may be abnormal only in cases with chronic portal hypertension or cirrhotic changes due to anatomical variation.

Anatomical variations in the PV have been a topic of analysis and interest for some time because of their impact on surgery and some interventional liver procedures. The range of prevalence varies from 0.09% to 24%. In a large series of 1,384 patients reviewed by Koc et al [12], the PV variation was reported to be 21.5%; similarly, Covey et al [10] recorded a 35% variation in patients via computed tomography portography for catheterization of the superior mesenteric artery. In our analysis, the percentage of PV anomalies was almost 25%, with the trifurcation of the PV (type II) being identified in 356 patients (9.6%) and the RpPV as the first branch of the main PV (type III) present in 306 patients (8.2%).

The above variants may be overlooked, and this can have important clinical consequences. Specifically, in the case of transhepatic PV embolization to induce contralateral liver hypertrophy, the radiologist must know the variant anatomy because embolizing a non-targeted segment can make potentially resectable anatomy unresectable because of insufficient hypertrophy. Similarly, in patients with type III variation, the RpPV catheterization can be more demanding and challenging. Variations like RPV trifurcation could lead to an unstable location of the catheter. In liver transplantation, a living donor who has a type II variant of the PV can suffer from complications associated with clamping; type III is even more complicated because the clamping must involve both the RaPV and RpPV [4, 25].

In conclusion, anatomic variations of the PV are relatively frequent. Adequate knowledge of these anomalies is important for radiologists and surgeons because of the increased demand for liver resections, transplantations and percutaneous hepatobiliary interventions. A preoperative imaging workup can help identify variations in the PV and reduce related morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Anastasios Katsourakis and Dimitrios Chytas. The first draft of the manuscript was written by George Noussios and Anastasios Katsourakis, and all the authors commented on previous versions. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

PV: portal vein; RPV: right portal vein; LPV: left portal vein; RpPV: right posterior portal vein; RaPV: right anterior portal vein

| References | ▴Top |

- Varotti G, Gondolesi GE, Goldman J, Wayne M, Florman SS, Schwartz ME, Miller CM, et al. Anatomic variations in right liver living donors. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(4):577-582.

doi pubmed - Lee VS, Morgan GR, Lin JC, Nazzaro CA, Chang JS, Teperman LW, Krinsky GA. Liver transplant donor candidates: associations between vascular and biliary anatomic variants. Liver Transpl. 2004;10(8):1049-1054.

doi pubmed - Nakamura T, Tanaka K, Kiuchi T, Kasahara M, Oike F, Ueda M, Kaihara S, et al. Anatomical variations and surgical strategies in right lobe living donor liver transplantation: lessons from 120 cases. Transplantation. 2002;73(12):1896-1903.

doi pubmed - Kamel IR, Kruskal JB, Pomfret EA, Keogan MT, Warmbrand G, Raptopoulos V. Impact of multidetector CT on donor selection and surgical planning before living adult right lobe liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(1):193-200.

doi pubmed - Fraser-Hill MA, Atri M, Bret PM, Aldis AE, Illescas FF, Herschorn SD. Intrahepatic portal venous system: variations demonstrated with duplex and color Doppler US. Radiology. 1990;177(2):523-526.

doi pubmed - Soyer P, Bluemke DA, Choti MA, Fishman EK. Variations in the intrahepatic portions of the hepatic and portal veins: findings on helical CT scans during arterial portography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(1):103-108.

doi pubmed - Erbay N, Raptopoulos V, Pomfret EA, Kamel IR, Kruskal JB. Living donor liver transplantation in adults: vascular variants important in surgical planning for donors and recipients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(1):109-114.

doi pubmed - Lee SG, Hwang S, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Park KM, Lee YJ, Moon DB, et al. Approach to anatomic variations of the graft portal vein in right lobe living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75(3 Suppl):S28-32.

doi pubmed - Akgul E, Inal M, Soyupak S, Binokay F, Aksungur E, Oguz M. Portal venous variations. Prevalence with contrast-enhanced helical CT. Acta Radiol. 2002;43(3):315-319.

doi pubmed - Covey AM, Brody LA, Getrajdman GI, Sofocleous CT, Brown KT. Incidence, patterns, and clinical relevance of variant portal vein anatomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(4):1055-1064.

doi pubmed - Atasoy C, Ozyurek E. Prevalence and types of main and right portal vein branching variations on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(3):676-681.

doi pubmed - Koc Z, Oguzkurt L, Ulusan S. Portal vein variations: clinical implications and frequencies in routine abdominal multidetector CT. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2007;13(2):75-80.

- Okten RS, Kucukay F, Dedeoglu H, Akdogan M, Kacar S, Bostanci B, Olcer T. Branching patterns of the main portal vein: effect on estimated remnant liver volume in preoperative evaluation of donors for liver transplantation. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(3):478-483.

doi pubmed - Sureka B, Patidar Y, Bansal K, Rajesh S, Agrawal N, Arora A. Portal vein variations in 1000 patients: surgical and radiological importance. Br J Radiol. 2015;88(1055):20150326.

doi pubmed - Hasanefendioglu Bayrak A, Nacar Dogan S, Ozturkmen Akay H. Clinical Importance of Main Portal Vein and Right Portal Vein Variations: A Prevalence Study With 128-Slice Multidetector Computed Tomography. Exp Clin Transplant. 2021.

doi pubmed - Nghiem HV, Dimas CT, McVicar JP, Perkins JD, Luna JA, Winter TC, 3rd, Harris A, et al. Impact of double helical CT and three-dimensional CT arteriography on surgical planning for hepatic transplantation. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24(3):278-284.

doi pubmed - Hu GH, Shen LG, Yang J, Mei JH, Zhu YF. Insight into congenital absence of the portal vein: is it rare? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(39):5969-5979.

doi pubmed - Walsh G, Williams MP. Congenital anomalies of the portal venous system—CT appearances with embryological considerations. Clin Radiol. 1995;50(3):174-176.

doi - Manjunatha YC, Beeregowda YC, Bhaskaran A. An unusual variant of the portal vein. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6(4):731-733.

- Madoff DC, Hicks ME, Vauthey JN, Charnsangavej C, Morello FA, Jr., Ahrar K, Wallace MJ, et al. Transhepatic portal vein embolization: anatomy, indications, and technical considerations. Radiographics. 2002;22(5):1063-1076.

doi pubmed - Sakuhara Y, Abo D, Hasegawa Y, Shimizu T, Kamiyama T, Hirano S, Fukumori D, et al. Preoperative percutaneous transhepatic portal vein embolization with ethanol injection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(4):914-922.

doi pubmed - Munguti J, Awori K, Odula P, Ogeng'o J. Conventional and variant termination of the portal vein in a black Kenyan population. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2013;72(1):57-62.

doi pubmed - Guerra A, De Gaetano AM, Infante A, Mele C, Marini MG, Rinninella E, Inchingolo R, et al. Imaging assessment of portal venous system: pictorial essay of normal anatomy, anatomic variants and congenital anomalies. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21(20):4477-4486.

- Corness JA, McHugh K, Roebuck DJ, Taylor AM. The portal vein in children: radiological review of congenital anomalies and acquired abnormalities. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(2):87-96, quiz 170-171.

doi pubmed - Schmidt S, Demartines N, Soler L, Schnyder P, Denys A. Portal vein normal anatomy and variants: implication for liver surgery and portal vein embolization. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2008;25(2):86-91.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.