| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 10, October 2018, pages 786-790

Methimazole-Induced Pauci-Immune Glomerulonephritis and Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome: An Important Association to Be Aware of

Huzaif Qaisara, Mohammad A. Hossaina, Monika Akulaa, Jennifer Chenga, Mayurkumar Patela, Zheng Minb, Halyna Kuzyshyna, Michael Levitta, Shana M. Coleyc, Arif Asifa, d

aDepartment of Medicine, Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Hackensack Meridian Health, Neptune, NJ 07753, USA

bDepartment of Pathology, Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Hackensack Meridian Health, Neptune, NJ 07753, USA

cDepartment of Pathology, Columbia University Medical Center, NY Presbyterian/Columbia, New York, NY 10032, USA

dCorresponding Author: Arif Asif, Department of Medicine, Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine at Seton Hall, 1945 Route 33, Neptune, NJ, USA

Manuscript submitted July 25, 2018, accepted August 30, 2018

Short title: Methimazole-Induced Glomerulonephritis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3530w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

While methimazole (MMI) is the first line treatment for hyperthyroidism, this medication is not devoid of adverse effects. In this article, we present a 70-year-old male who admitted the hospital with right lower extremity pain and rash. The patient was recently treated with MMI for hyperthyroidism. Imaging studies revealed bilateral renal and splenic infarcts along with thrombosis of popliteal artery. Laboratory data revealed hematuria and proteinuria with positive (MPO), anti-proteinase-3 (PR3) and anti-cardiolipin IgG antibodies. Renal biopsy revealed pauci-immune glomerulonephritis and features with anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome (APS). MMI was discontinued and the patient was treated successfully with steroid therapy and anti-coagulation with resolution of proteinuria, hematuria and normalization of laboratory parameters. While MMI-induced pauci-immune glomerulonephritis has been previously reported, its association with APS has never been described before. Our case demonstrates that this rare diagnosis can be treated by early withdrawal of MMI and initiation of steroids along with anticoagulation.

Keywords: Methimazole; Pauci-immune; Crescentic glomerulonephritis; ANA; Glucocorticosteroids

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis (PICGN) is a form of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) characterized by necrotizing features and absence or paucity of immune deposits [1]. Multiple medications have been reported to be associated with in literature review including propylthiouracil [2-6]. Methimazole (MMI)-induced pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis has been reported rarely in the past [7, 8]; however, co-occurrence of catastrophic anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) is a potentially life-threatening adverse effect that has never been reported with MMI. Understanding the possibility of MMI-induced PCIGN with APS is of utmost importance, as early withdrawal of MMI and administration of steroids with or without immunosuppressant improve prognosis and survival [2, 4, 9]. In this article, we present a case of biopsy-proven MMI-induced PICGN which also had features of APS.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 70-year-old Caucasian male underwent bio-prosthetic aortic valve replacement (AVR). In the same hospitalization, he was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism and MMI 10 mg twice a day was initiated with subsequent successful maintenance of euthyroid status. Ten months after the AVR, he presented with fever, generalized fatigue and malaise. He was diagnosed with possible subacute endocarditis with streptococcus mutans bacteremia and started on appropriate intravenous antibiotic. Transesophageal echo was negative for vegetation. CT scan of the chest and abdomen showed wedge-shaped decreased attenuation in the right kidney and spleen consistent with infarcts. Hypercoagulable workup was positive for anti-cardiolipin IgG antibody at a high titer of 124 (normal < 20) and APS was suspected. The patient was discharged to rehab on ceftriaxone, gentamicin and enoxaparin. Ten days later, he presented with right lower extremity severe pain, rash and fever for 1 day. On physical examination, he was found to have significant tenderness in the right leg from knee and down as well as tender red and purple discolored spots on the skin that did not blanch. Vitals were unremarkable except for fever at 102.2 °F. Laboratory data (Table 1) revealed normal leukocytes counts, low hemoglobin (8.5 gm/dL), normal platelet count, and blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine. Inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were elevated (114 mm/first hour and 15.28, respectively) compared to 10 days ago. Urinalysis was positive for hematuria and proteinuria. Urine protein/creatinine ratio was high at 2,124 (normal: 0 – 200 mg/g) and 24-h urine total protein at 1,168 (normal: 0 – 150 mg). The patient had normal free T4 1.02 (0.5 - 1.26 ng/dL) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.750 (0.300 - 4.500 U/mL). Thyroid peroxidase antibodies 0.6 (normal: 0 - 9 IU/mL) and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin 109 units (normal < 122 units) were in normal range. However, laboratory data revealed positive myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodies with a titer of 50 (normal value: < 20 AU/mL) and positive proteinase 3 (PR3) antibodies with a titer of 32 (normal value < 14 IU/mL), but negative anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) by immunofluorescence (IFA). Rheumatoid factor was elevated at 38.9 (normal < 20). ANA, SSA, SSB, anti-Smith, RNP and double-stranded DNA antibodies were all-negative and complement levels C3 and C4 were normal. Vascular workup revealed right lower extremity moderate arterial insufficiency due to occlusion at the level of the popliteal artery and proximal peroneal artery due to arterial thrombosis. MMI-induced ANCA-associated vasculitis and catastrophic APS was suspected. MMI was discontinued and the patient was treated with pulse dose of intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone for 3 days and high-intensity heparin drip bridging with coumadin. Then, he was continued on prednisone 60 mg daily and coumadin with an international normalized ratio (INR) goal between 2 and 3. Over the next week, right leg pain and purpuric rash significantly improved and eventually resolved, hematuria and proteinuria significantly improved, and ESR and CRP trended down.

Click to view | Table 1. Summary of Laboratory Results |

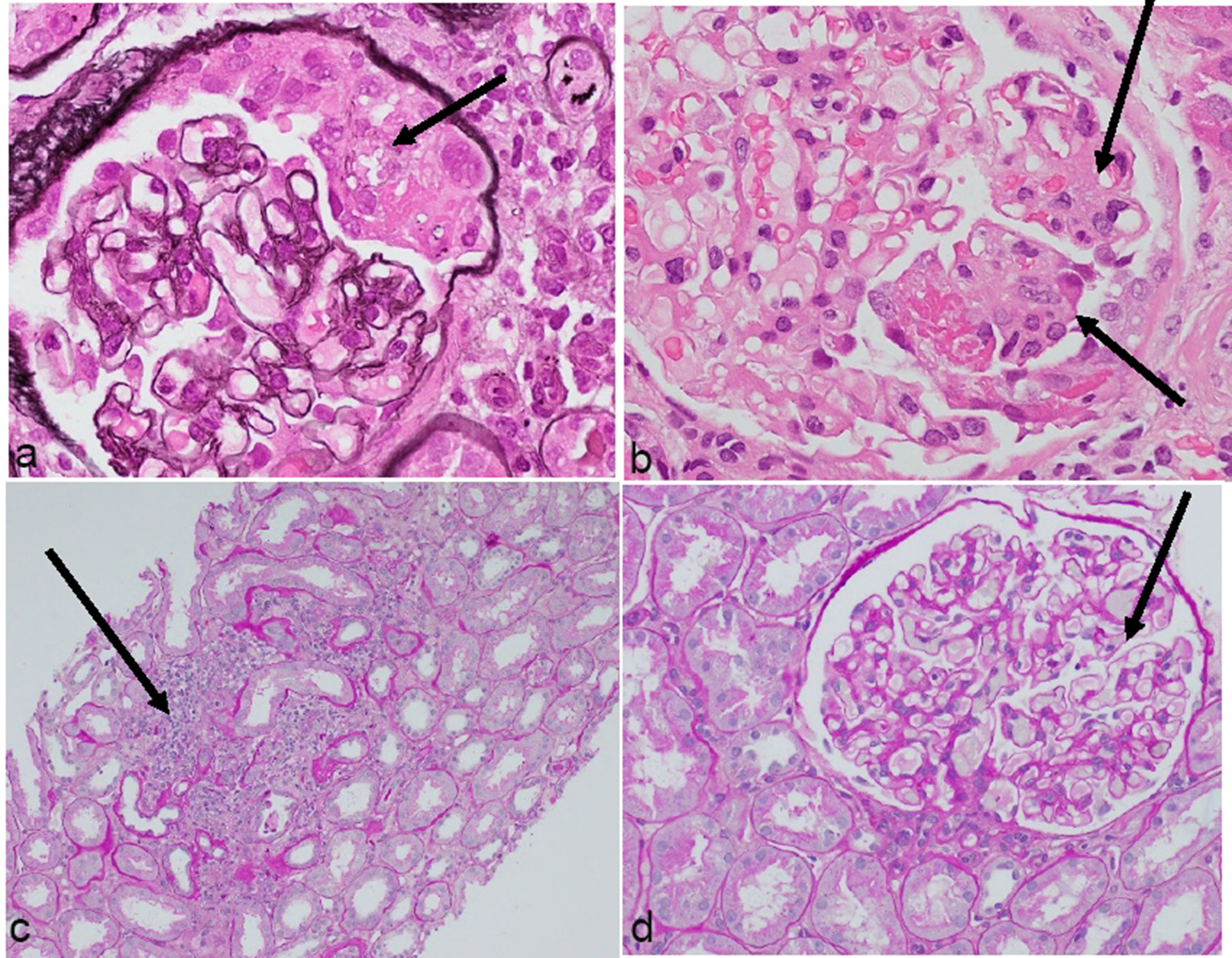

Renal biopsy revealed pauci-immune focal necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis with focal segmental sclerosing features (Fig. 1). Immunofluorescence microscopy did not show any immune complex deposits but showed mild sub-endothelial widening by electron lucent material suggestive of focal acute process of thrombotic microangiopathy. Presence of MPO and PR3 positivity with ANCA negativity in pauci-immune glomerulonephritis supported diagnosis of drug-induced vasculitis, in this case, MMI-induced. The interesting finding of thrombotic microangiopathy on renal biopsy confirmed APS. At 10-day follow-up, MPO antibody, PR3 antibody and ANA became negative reflecting good response to steroids. Repeat MPO and PR-3 with absent proteinuria on day 45 after discharge confirmed complete recovery from PICGN.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Representative photomicrographs of glomerular changes consistent with pauci-immune focal necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis. (a) Cellular crescent. (b) Segmental fibrinoid necrosis. (c) Patchy scarring with inflammation. (d) Normal glomerulus (H&E, ×400). |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Drug-induced ANCA-positive PICGN has been reported previously with propylthiouracil (PTU) [2, 3, 5, 6] and carbimazole [10]. However, MMI has been reported as etiology of this form of RPGN in only one case report in 1996 [7]. In that case report, patient had been on MMI 5 - 10 mg for nearly 6 years and became hypothyroid. MMI was stopped for 3 months and subsequently restarted at a dose of 5 mg daily. As a part of block and replace therapy, MMI was gradually increased to 30 mg daily followed by 45 mg daily. With this change, the patient started experiencing cough, fever, and lower extremity myalgia with increment in serum creatinine. P-ANCA and C-ANCA positivity suggested the diagnosis of PICGN. Renal biopsy confirmed crescentic glomerulonephritis with no immune deposits on IFA. The patient demonstrated positive response to steroid therapy with improvement in serum creatinine. Our patient has been on MMI for 10 months (compared to the 6 years on MMI in the case reported by Hori et al [7]) before the development of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. When MMI was stopped, creatinine quickly improved with good response to steroids in our and the case reported by Hori et al [7]. Our case is unique because of rarity of MMI-induced PICGN-associated APS as renal biopsy demonstrated both features of PICGN and APS.

MMI has been rarely associated with cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis [11], ANCA-associated vasculitis with alveolar hemorrhage [12], central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis [13] and drug-induced lupus [14]. Early diagnosis and management is crucial because a delay in identifying MMI as etiology of drug-induced ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) with RPGN can lead to continuous exposure of this drug and development of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [15]. In our case, MMI-induced PICGN was diagnosed before development of renal failure as patient did have co-presentation of APS-induced infarct in context of recently diagnosed sub-acute infective endocarditis with absent vegetation on transesophageal echocardiography. This presentation along with nephrotic range proteinuria, led the medicine team to order ANCA and other autoimmune workup with consult to nephrology to evaluate proteinuria and renal infarct.

PICGN is a type of RPGN that corresponds to necrotizing glomerular inflammation in absence or paucity of immune deposits on IFA or electron microscopy [1]. It can lead to ESRD if timely management and intervention is not undertaken [15]. Majority of these cases are attributed to granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) [16]; however, drug-induced PICGN has also been reported as in our case [5, 7]. Mostly drug-induced PICGN is ANCA (perinuclear ANCA against MPO and cytoplasmic ANCA against PR-3)-positive but can also be ANCA-negative [17, 18]. Drug-induced inciting event that triggers immune mechanisms in the body facilitated by cytokines leading to production of ANCA, plays its role in PICGN [19, 20]. Clinical presentation includes constitutional symptoms, oliguria or anuria, hematuria (dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) with RBC casts), proteinuria (> 500 mg/day) in the setting of rising blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine [21].

RPGN has broad differential diagnosis. Renal biopsy is the backbone of diagnosis that shows IFA finding of absence or paucity of immune deposits and necrotizing glomerulonephritis [22]. Anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome can be confirmed by having thrombotic microangiopathy on renal biopsy as was the scenario in our case [23].

Discontinuation of MMI and empiric treatment with intravenous pulse steroids (500 - 1,000 mg methylprednisolone daily for 3 days) should be started particularly if delay in renal biopsy is expected [24]. Delay in starting treatment may lead to ESRD requiring hemodialysis (HD). Plasmapheresis and immunosuppressive agents including cyclophosphamide, rituximab and azathioprine may play important role in treatment [24, 25] but needs further study and evaluation in MMI-induced PICGN. We did not use any immunosuppressive agent other than steroid therapy.

Conclusions

MMI can induce PICGN, a rapidly progressive condition leading to renal failure within days or weeks and is potentially life-threatening. ESRD can be prevented by timely discontinuation of MMI. Once PICGN is suspected, nephrology service should be consulted and appropriate therapy should be considered, including steroids. With comprehensive examinations in our case, we also found the presence of high titers of anticardiolipin IgG antibodies and focal acute process of thrombotic microangiopathy on renal biopsy which confirmed the presence of co-existing APS. Right kidney and spleen infarcts, and right popliteal artery occlusion also provided support to the co-existing diagnosis of APS. Anticoagulation was successfully instituted. Clinicians including internist, endocrinologist and nephrologist should be aware of the potential complication of MMI and be vigilant while patients are on MMI therapy for early diagnosis and intervention that can prevent permanent kidney damage and vascular complications.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this report would like to acknowledge the assistance of the following Departments at Jersey Shore University Medical Center: Internal Medicine, Departments of Pathology, Department of Nephrology and Department of Rheumatology.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Financial Support

This project was not supported by any grant or funding agencies.

Consent

The patient described in the case report had given informed consent for the case report to be published.

| References | ▴Top |

- Scaglioni V, Scolnik M, Catoggio LJ, Christiansen SB, Varela CF, Greloni G, Rosa-Diez G, et al. ANCA-associated pauci-immune glomerulonephritis: always pauci-immune? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35 Suppl 103(1):55-58.

- Kantachuvesiri P, Chalermsanyakorn P, Phakdeekitcharoen B, Lothuvachai T, Niticharoenpong K, Radinahamed P, Turner N, et al. Propylthiouracil-associated rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis with double positive anti-glomerular basement membrane and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody: the first case report. CEN Case Rep. 2015;4(2):180-184.

doi pubmed - Poomthavorn P, Mahachoklertwattana P, Tapaneya-Olarn W, Chuansumrit A, Chunharas A. Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody-positive systemic vasculitis associated with propylthiouracil therapy: report of 2 children with Graves' disease. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85(Suppl 4):S1295-1301.

pubmed - Gao Y, Zhao MH. Review article: Drug-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2009;14(1):33-41.

doi pubmed - Kudoh Y, Kuroda S, Shimamoto K, Iimura O. Propylthiouracil-induced rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. Clin Nephrol. 1997;48(1):41-43.

pubmed - Chen Y, Bao H, Liu Z, Zhang H, Zeng C, Liu Z, Hu W. Clinico-pathological features and outcomes of patients with propylthiouracil-associated ANCA vasculitis with renal involvement. J Nephrol. 2014;27(2):159-164.

doi pubmed - Hori Y, Arizono K, Hara S, Kawai R, Hara M, Yamada A. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-positive crescentic glomerulonephritis associated with thiamazole therapy. Nephron. 1996;74(4):734-735.

doi pubmed - Rampelli SK, Rajesh NG, Srinivas BH, Harichandra Kumar KT, Swaminathan RP, Priyamvada PS. Clinical spectrum and outcomes of crescentic glomerulonephritis: A single center experience. Indian J Nephrol. 2016;26(4):252-256.

doi pubmed - Bakhtar O, Thajudeen B, Braunhut BL, Yost SE, Bracamonte ER, Sussman AN, Kaplan B. A case of thrombotic microangiopathy associated with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome successfully treated with eculizumab. Transplantation. 2014;98(3):e17-18.

doi pubmed - Calanas-Continente A, Espinosa M, Manzano-Garcia G, Santamaria R, Lopez-Rubio F, Aljama P. Necrotizing glomerulonephritis and pulmonary hemorrhage associated with carbimazole therapy. Thyroid. 2005;15(3):286-288.

doi pubmed - Mustafa K, Nadir G, Ali HP. A case of methimazole induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Turkish Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;4:125-127.

- Tsai MH, Chang YL, Wu VC, Chang CC, Huang TS. Methimazole-induced pulmonary hemorrhage associated with antimyeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody: a case report. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001;100(11):772-775.

pubmed - Tripodi PF, Ruggeri RM, Campenni A, Cucinotta M, Mirto A, Lo Gullo R, Baldari S, et al. Central nervous system vasculitis after starting methimazole in a woman with Graves' disease. Thyroid. 2008;18(9):1011-1013.

doi pubmed - Wang LC, Tsai WY, Yang YH, Chiang BL. Methimazole-induced lupus erythematosus: a case report. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2003;36(4):278-281.

pubmed - Moroni G, Ponticelli C. Rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis: Early treatment is a must. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(7):723-729.

doi pubmed - Rowaiye OO, Kusztal M, Klinger M. The kidneys and ANCA-associated vasculitis: from pathogenesis to diagnosis. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(3):343-350.

doi pubmed - Shah S, Havill J, Rahman MH, Geetha D. A historical study of American patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody negative pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(4):953-960.

doi pubmed - Sharma A, Nada R, Naidu GS, Minz RW, Kohli HS, Sakhuja V, Gupta KL, et al. Pauci-immune glomerulonephritis: does negativity of anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies matters? Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19(1):74-81.

doi pubmed - Naidu GS, Sharma A, Nada R, Kohli HS, Jha V, Gupta KL, Sakhuja V, et al. Histopathological classification of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis and its impact on outcome. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(12):1721-1727.

doi pubmed - Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Song Q, Lan HY. Modulators of crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(11):2271-2278.

pubmed - Baldwin DS, Neugarten J, Feiner HD, Gluck M, Spinowitz B. The existence of a protracted course in crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1987;31(3):790-794.

doi pubmed - Gupta P, Rana DS. Importance of renal biopsy in patients aged 60 years and older: Experience from a tertiary care hospital. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29(1):140-144.

doi pubmed - Tektonidou MG. Renal involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS)-APS nephropathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36(2-3):131-140.

doi pubmed - Bruns FJ, Adler S, Fraley DS, Segel DP. Long-term follow-up of aggressively treated idiopathic rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Am J Med. 1989;86(4):400-406.

doi - Couser WG. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis: classification, pathogenetic mechanisms, and therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1988;11(6):449-464.

doi

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.