| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 2, February 2018, pages 154-157

Successful Treatment of Rapidly Progressive Life-Threatening Esophageal Submucosal Hematoma in a Patient With van der Hoeve Syndrome

Yasuhiro Watanabea, Naomi Shimizua, e, Masahiro Iwakawaa, Takashi Yamaguchia, Noriko Bana, Hidetoshi Kawanaa, Atsuhito Saikia, Emiko Sakaidab, Chiaki Nakasekob, Yasuhiro Matsuurac, Nobuyuki Aotsukac, Hideaki Bujod, Ichiro Tatsunoa

aCenter for Diabetes, Metabolism, and Endocrinology, Toho University Medical Center Sakura Hospital, 564-1 Shimoshizu Sakura, Chiba, Japan

bDepartment of Hematology, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan

cDepartment of Hematology, Narita Japanese Red Cross National Hospital, Narita, Chiba, Japan

dDepartment of Clinical Laboratory Medicine, Toho University Medical Center Sakura Hospital, Sakura, Chiba, Japan

eCorresponding Author: Naomi Shimizu, Department of Blood Transfusion, Toho University Medical Center Sakura Hospital, 564-1 Shimoshizu, Sakura-City, Chiba 285-8741, Japan

Manuscript submitted November 13, 2017, accepted December 2, 2017

Short title: Huge Hematoma in van der Hoeve Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3270w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a rare inherited disorder of the connective tissue with many reports on its association with bleeding diatheses. OI patients with blue sclera, hearing loss, and bone vulnerability are classified as having van der Hoeve syndrome. Here, we report the first case of rapidly progressing, massive esophageal submucosal hematoma in this syndrome. Bleeding in OI is reportedly due to defective capillary integrity and platelet dysfunction; however, our patient did not show such findings. Multiple factors contributed to the bleeding diathesis, including dysfunction of platelet and platelet-endothelial cell interaction, which could not be proven in vitro.

Keywords: Van der Hoeve syndrome; Osteogenesis imperfecta; Esophageal submucosal hematoma; Platelet dysfunction; Capillary fragility

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a rare congenital disease that exhibits various degrees of connective tissue dysfunction, in addition to easy bone fracturing, due to bone fragility and progressive bone deformity [1, 2]. The birth prevalence of OI has been reported to be approximately 6 - 7/100,000 people [3]. In the International Classification of Genetic Skeletal Disorders, OI has been classified into types I-IV by Sillence [4]. Van der Hoeve syndrome is classified as type I and is mainly caused by the COL1A1 gene mutation with easy bone fracturing, blue sclera, and hearing loss as the triad of clinical features. In general, its inheritance is autosomal dominant [5].

In OI, approximately two-thirds of patients have a bleeding tendency due to capillary vulnerability and abnormal platelet function [6]. Indeed, there have been several reports regarding bleeding episodes, including subdural hematoma [7], intracerebral hemorrhage [8], retinal bleeding [9], bleeding at birth [10], skin petechial bleeding [11], and parathyroid bleeding [12]. Here, we report the first case of massive hematoma under the esophageal mucosa in a patient with van der Hoeve syndrome without apparent coagulation factor or platelet function abnormalities.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 47-year-old female was admitted to our hospital in January 2016 in an ambulance with a 1-week history of abdominal pain, vomiting, and a small amount of hematemesis. On physical examination, her blood pressure was 74/42 mm Hg, heart rate was 107 beats/min, respiratory rate was 25 breaths/min, SpO2 was 99% on room air, and body mass index (BMI) was 16.2 kg/m2. She had conjunctival pallor indicative of anemia, blue sclera, and generalized hyperextension of the skin but not of the hand, elbow, or knee joint. The Rumpel-Leede phenomenon was not present. There was tenderness around the umbilicus.

In her past medical history, she had suffered more than 10 fractures, including clavicle fracture soon after birth, rib fracture on a crowded train, and after sneezing. Moreover, she had a history of massive hemorrhage during Cesarean delivery at age 34. She developed hearing loss around age 45; she was then diagnosed with van der Hoeve syndrome on account of the additional signs of blue sclera and dental aplasia. In her family history, her daughter, father, grandmother, uncle, aunt, and cousin also had blue sclera and a history of multiple fractures.

The laboratory findings showed an elevation of transaminase, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP), serum creatinine, uric acid, and white blood cell count. Platelet count and coagulation tests were almost normal (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Laboratory Data on Admission |

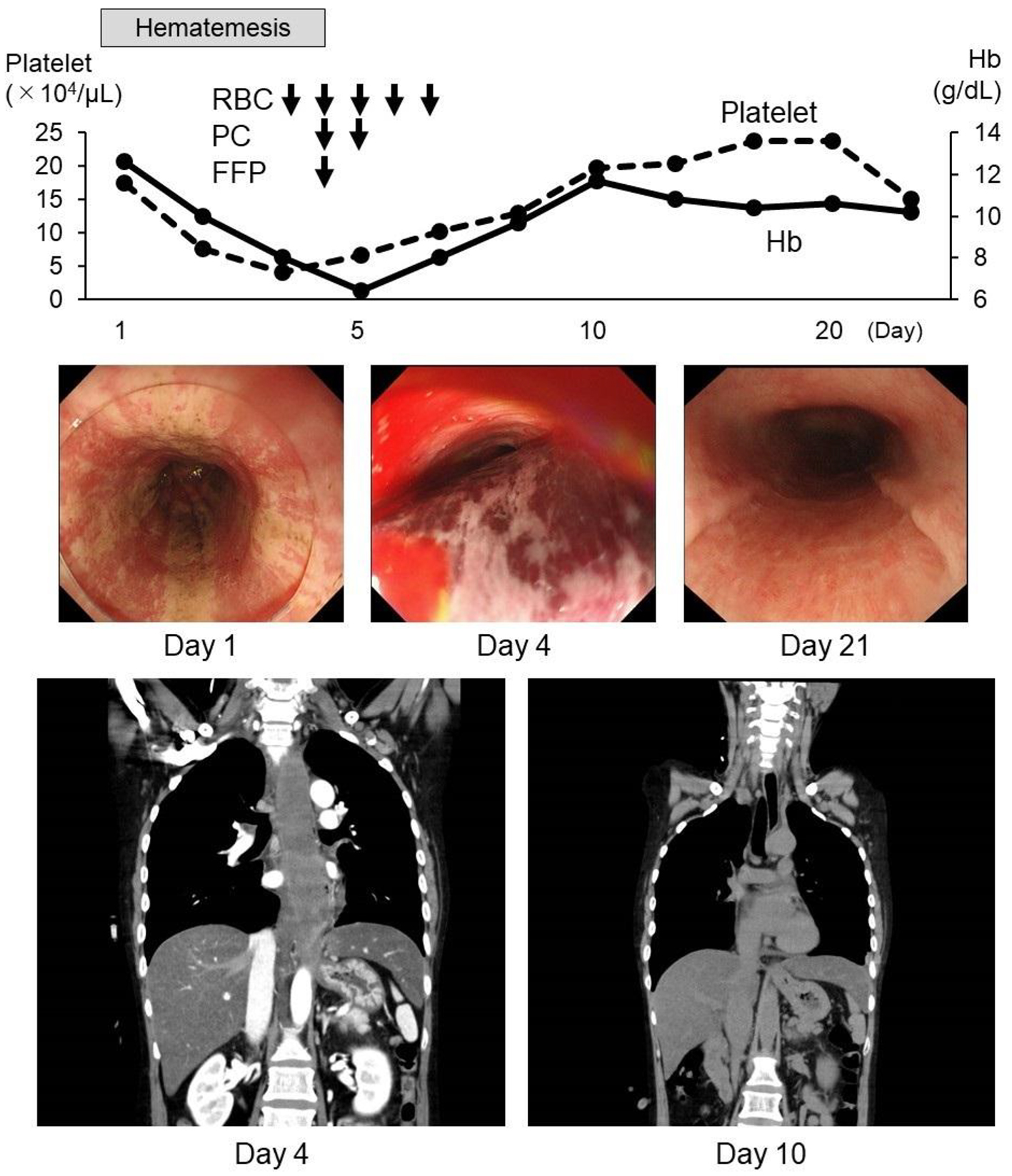

The small amount of hematemesis continued after admission; however, emergency upper gastrointestinal endoscopic and computed tomography (CT) examination did not reveal the source of bleeding. However, hematemesis was still present 2 days after admission and she was treated with total parenteral nutrition under fasting conditions and was also given carbazochrome sodium sulfonate and tranexamic acid as hemostatic agents. Under these treatments, the hemoglobin and platelet count decreased to 6.8 g/dL and 4.7 × 104/µL, respectively, on day 3 after admission and she was given red blood cells (RBCs), platelet concentrate (PC), and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusions. Second upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination on day 4 revealed a massive submucosal hematoma from the upper part to the lower part of the esophagus. Chest CT also revealed a massive esophageal hematoma with a maximum diameter of 36 × 36 mm and total length of 170 mm (Fig. 1). On the same day, the platelet count was 4.1 × 104 /µL, and the bleeding time was prolonged to more than 10 min. Coagulation data, including international normalized ratio of prothrombin time (PT-INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), coagulation factors 8, 9, 13, and von Willebrand factor (vWF), were normal. After two PC transfusions and one FFP transfusion, the platelet counts gradually recovered and chest CT on day 10 showed remarkable improvement. The massive esophageal submucosal hematoma was seen to completely diminish on performing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy on day 21. Renal dysfunction because of dehydration on admission was improved on the next day with fluid replacement, and liver dysfunction with shock liver involvement in fatty liver also gradually improved after admission.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Clinical course. Hematemesis continued after admission and a massive esophageal submucosal hematoma was found during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and computed tomography (CT) on day 4. Anemia and thrombocytopenia also progressed, and transfusions of RBC, PC, and FFP were administered. After the transfusions, the submucosal hematoma was rapidly absorbed. RBC: red blood cell transfusion, 2 units; PC: platelet concentrate, 10 units; FFP: fresh frozen plasma, 2 units. |

Expression of platelet surface antigen, CD41, and CD42b on flow cytometry was normal. There were no abnormalities of platelet aggregation, including on addition of adenosine diphosphate (ADP), collagen, epinephrine, and ristocetin. Genetic tests did not reveal gene mutations, including COL1A1 or COL1A2.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Here, we report a case of van der Hoeve syndrome with rapidly progressive massive esophageal submucosal hematoma that was successfully treated by transfusions of RBC, PC, and FFP. In this case, endoscopic findings did not suggest Mallory-Weiss syndrome and the massive esophageal submucosal hematoma progressed rapidly and improved promptly (Fig. 1).

In this case, the cause of massive esophageal submucosal hematoma was thought to be a bleeding tendency secondary to OI. William et al reported that platelet aggregation induced by ADP was inhibited in almost all 30 cases of OI [13]. However, in this case, platelet aggregation testing and coagulation factors, including vWF, were normal. It has previously been reported that dysfunction of platelet-endothelial cell interaction in OI is difficult to detect on platelet aggregation testing [14]. The platelet count was 4.7 × 104/µL at the time of rapid progression of the massive esophageal submucosal bleeding and PC transfusions were not essential in this situation. However, after PC and FFP transfusions with normal aggregating ability, submucosal bleeding rapidly disappeared.

Vulnerability of connective tissue has been reported as being another bleeding tendency factor in OI [15]. Evensen et al reported capillary fragility in approximately 35% of OI cases [6]. In this case, skin hyperextension was observed; however, there were no findings of benign joint hypermobility syndrome [16] and the Rumpel-Leede test was negative. In our patient, the bleeding time was evaluated at the low platelet number (4.7 × 104/mL). So, the prolongation of bleeding time was affected by low platelet count. However, in her past history, the abnormal bleeding during cesarean delivery occurred with normal platelet count. So, platelet dysfunction and defective capillary integrity were considered as factors contributing to the abnormal submucosal hematoma because although laboratory data, PT, and APTT were normal, bleeding time was prolonged.

Genetic abnormalities, including COL1A1 and COL1A2, are reportedly detected in 97% of mild OI cases [17]. This patient was mild OI, so, we speculated the detection of genetic mutations of COL1A1 or COL1A2. However, the genetic mutations of COL1A1, COL1A2 and other genes including LEPRE1, CRTAP, PPIB, SERPINH1, SERPINF1, SP7, BMP1, FKBP10, WNT1, PLOD2, IFITM5, LRP5, TMEM38B, SEC24D and SPARC were not detected (The translated region of the target gene was analyzed with the SureSelect Target Enrichment System after DNA fragmentation). Bardai et al reported that there were no genetic mutations in 3% in these patients [2]. So, our case was included in this category. No reports have shown a relationship between genetic abnormalities and a bleeding tendency in OI.

Here, we report on the successful treatment with RBC, PC, and FFP transfusions of life-threatening massive esophageal submucosal hematoma in a case of van der Hoeve syndrome. PC and FFP transfusions with normal aggregating ability were useful for the management of bleeding symptoms in this case of OI. Abnormal bleeding was caused by dysfunction of platelet and platelet-endothelial cell interaction, which could not be proven in vitro.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the staff members in our departments who contributed to this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

| References | ▴Top |

- Rauch F, Glorieux FH. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet. 2004;363(9418):1377-1385.

doi - Zhao X, Yan SG. Recent progress in osteogenesis imperfecta. Orthop Surg. 2011;3(2):127-130.

doi pubmed - van Dijk FS, Cobben JM, Kariminejad A, Maugeri A, Nikkels PG, van Rijn RR, Pals G. Osteogenesis imperfecta: a review with clinical examples. Mol Syndromol. 2011;2(1):1-20.

doi - Bonafe L, Cormier-Daire V, Hall C, Lachman R, Mortier G, Mundlos S, Nishimura G, et al. Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2015 revision. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(12):2869-2892.

doi pubmed - Sykes B, Ogilvie D, Wordsworth P, Wallis G, Mathew C, Beighton P, Nicholls A, et al. Consistent linkage of dominantly inherited osteogenesis imperfecta to the type I collagen loci: COL1A1 and COL1A2. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46(2):293-307.

pubmed - Evensen SA, Myhre L, Stormorken H. Haemostatic studies in osteogenesis imperfecta. Scand J Haematol. 1984;33(2):177-179.

doi pubmed - Eddeine HS, Dafer RM, Schneck MJ, Biller J. Bilateral subdural hematomas in an adult with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18(4):313-315.

doi pubmed - Goddeau RP, Jr., Caplan LR, Alhazzani AA. Intraparenchymal hemorrhage in a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 deficiency. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(2):236-238.

doi pubmed - Ganesh A, Jenny C, Geyer J, Shouldice M, Levin AV. Retinal hemorrhages in type I osteogenesis imperfecta after minor trauma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(7):1428-1431.

doi pubmed - Ruiter-Ligeti J, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Spence AR, Tulandi T, Abenhaim HA. Pregnancy outcomes in women with osteogenesis imperfecta: a retrospective cohort study. J Perinatol. 2016;36(10):828-831.

doi pubmed - Mondal RK, Mann U, Sharma M. Osteogenesis imperfecta with bleeding diathesis. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70(1):95-96.

doi pubmed - Knisely AS, Magid MS, Felix JC, Singer DB. Parathyroid gland hemorrhage in perinatally lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr. 1988;112(5):720-725.

doi - Hathaway WE, Solomons CC, Ott JE. Platelet function and pyrophosphates in osteogenesis imperfecta. Blood. 1972;39(4):500-509.

pubmed - Keegan MT, Whatcott BD, Harrison BA. Osteogenesis imperfecta, perioperative bleeding, and desmopressin. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(4):1011-1013.

doi pubmed - Malfait F, Symoens S, Goemans N, Gyftodimou Y, Holmberg E, Lopez-Gonzalez V, Mortier G, et al. Helical mutations in type I collagen that affect the processing of the amino-propeptide result in an Osteogenesis Imperfecta/Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome overlap syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:78.

doi pubmed - Jackson SC, Odiaman L, Card RT, van der Bom JG, Poon MC. Suspected collagen disorders in the bleeding disorder clinic: a case-control study. Haemophilia. 2013;19(2):246-250.

doi pubmed - Bardai G, Moffatt P, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. DNA sequence analysis in 598 individuals with a clinical diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta: diagnostic yield and mutation spectrum. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(12):3607-3613.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.