| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Original Article

Volume 9, Number 7, July 2017, pages 613-617

Mini-Laparoscopic Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery for Benign Adnexal Masses

Servet Gencdala, c, Huseyin Aydogmusa, Serpil Aydogmusb, Zafer Kolsuza, Sefa Kelekcib

aObstetrics and Gynecology Clinic, Izmir Ataturk Education and Research Hospital, Ministry of Health, Izmir, Turkey

bDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Izmir Katip Celebi University, Izmir, Turkey

cCorresponding Author: Servet Gencdal, Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic, Izmir Ataturk Education and Research Hospital, Ministry of Health, Izmir, Turkey

Manuscript accepted for publication May 08, 2017

Short title: MLS Versus CLS for Benign Adnexal Mass

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3060w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Minimally invasive endoscopic surgery has become an acceptable method for gynecologic indications for more than 20 years. We aimed to compare clinical and surgical outcomes between mini-laparoscopic surgery (MLS) and conventional laparoscopic surgery (CLS) for benign adnexal masses. As far as we know, no comparative study exists between these two minimal invasive procedures.

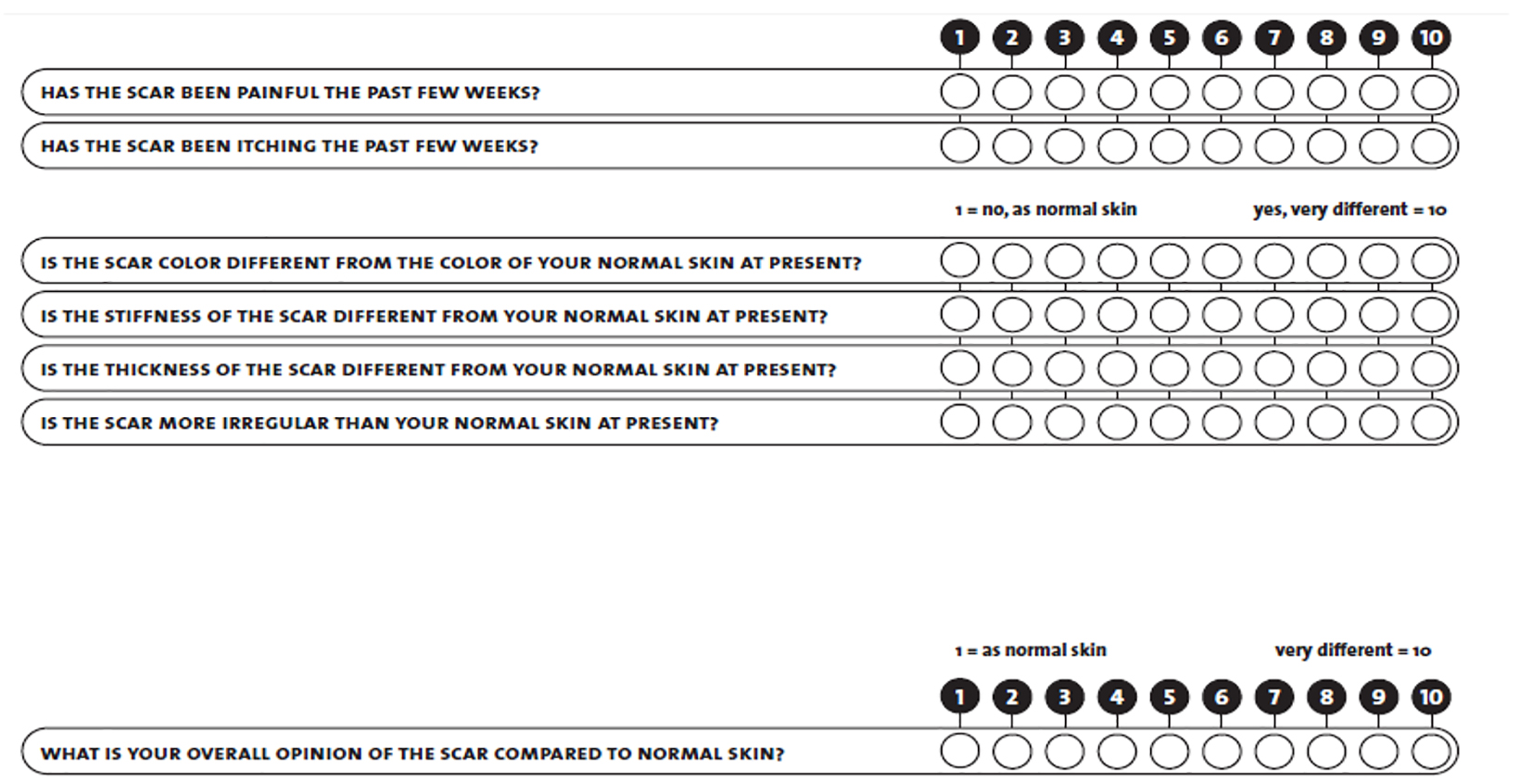

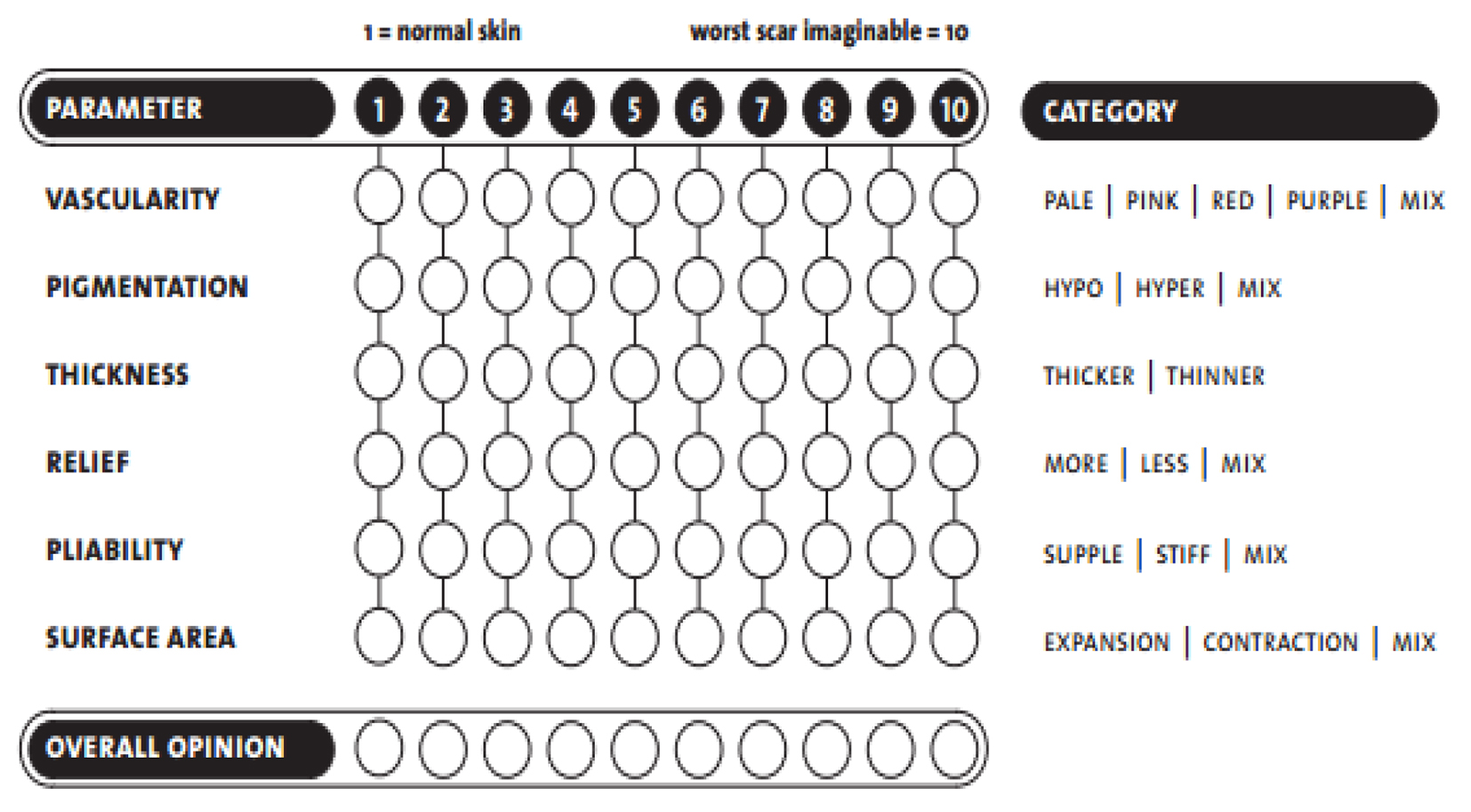

Methods: During the period between January 2014 and December 2016, a total number of 132 laparoscopic surgeries were performed for bening adnexal masses in our clinic. Seventy women underwent CLS and 62 women underwent MLS. Pathological results and operating time of procedures, estimated blood loss, preoperative and postoperative complications, patient scale and observer scale (POSAS) and length of hospital stay were recorded.

Results: There was no difference between the two groups regarding preoperative diagnosis, intraoperative surgical procedure performed, and length of hospital stay. The groups were compared in terms of postoperative pathological diagnosis using the Chi-square test, and there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups. Comparing the operation time and hematocrit change, there were statistically significant differences between the two groups. Both patient and observer PSOAS scar scores were better in MLS group (P < 0.05).

Conclusions: Mini-laparoscopy can be safely and effectively used to perform benign adnexal mass surgery.

Keywords: Benign adnexal masses; Conventional laparoscopy; Mini-laparoscopy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Benign adnexal masses are a common health problem for women of all age groups. Although management options depend on the clinical picture and considerations for malignancy, laparoscopic surgery has become the method of choice, particularly for benign cases as it has outcomes similar to open surgery along with certain advantages, including shorter recovery times and less pain during the postoperative period [1, 2]. Due to the rapid development of modern laparoscopic surgery, surgeons have gotten more chance to use minimally invasive techniques for almost all kinds of surgeries. One of the recent advancements in the field of minimally invasive surgery is mini-laparoscopy. Mini-laparoscopy is defined as surgery with instruments that are 2 - 5 mm in diameter, with the only possible exception of using larger diameter optics at the umbilicus [3]. During the last years, several mini-laparoscopic procedures have been successfully performed in various surgical fields [4]. But, up to now, no comparative study exists between mini-laparoscopic surgery (MLS) and conventional laparoscopic surgery (CLS) for benign adnexal masses.

In our study, we aimed to report a comparison of the intra- and postoperative results between these two minimally invasive approaches.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This retrospective study was conducted at Izmir Katip Celebi University Ataturk Education and Research Hospital between January 2014 and December 2016. Informed consents were obtained from all of the patients. Totally 132 consecutive patients who need laparoscopic surgery for benign adnexal masses were enrolled in the study. All patients were called to the hospital by telephone for skin scar formation with patient scale and observer scale (POSAS) (Figs. 1 and 2) [5]. The exclusion criteria were: 1) patients who were converted to laparotomy from laparoscopy, and 2) patients who have incision scar on their anterior abdominal wall. CLS was made with one 12-mm port for a 10-mm laparoscope and three 5-mm ports. MLS was made with one 5-mm port for a 5-mm laparoscope as well as two or three 3-mm ancillary trocars.

Click for large image | Figure 1. PSOAS patient scale (6 - 60). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. PSOAS observer scale (5 - 50). |

Surgical method

Operative laparoscopy was performed under general anesthesia in all women. Bladder catheterization was performed for all patients. After the pneumoperitoneum was created using a Veress needle, laparoscope (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) was introduced through the umbilicus. Two or three 3-mm ancillary trocars were inserted under direct visualization in the lower abdomen. Following abdominal exploration, the patients were placed into the Trendelenburg position. Depending on the preoperative findings and intraoperative diagnosis, cystectomy, oophorectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy or cystectomy and ovarian detorsion were performed. In general, the procedure was performed most commonly using bipolar coagulation and scissors. Specimens in conventional laparoscopy group were extracted directly from the incision or by using an endo-bag if necessary. When required, one of the accessory ports was enlarged to 1.5 - 2 cm to allow the extraction of the specimen in this group. Specimens in mini-laparoscopy group, a disposable specimen bag (EndobagTR, Covidien), were placed into posterior fornix and were pushed out slightly towards the vaginal wall between uterosacral ligaments (USLs). Under the guidance of reflux generated by the device, a transverse, 1 cm incision was made by 5 mm mono polar hook through bilateral USLs. Specimen bag was pushed into the abdomen from the opening. After placing specimen into the bag, ropes of the bag were pulled gently and bag was taken out of the body. For the patients who experienced difficulties due to high size, bag ropes were loosened and the specimen was removed by pulling the pieces out with Kocher clamps with the care of not to tear the bag. After the completion of extraction, colpotomy was closed with 2-0 synthetic absorbable suture. After reinssuflation of abdomen and control for bleeding, operation was terminated. All patients were assessed by the same two physicians after at least 3 months about skin scar development. At the same time, all patients evaluated themselves about their skin scar formation with POSAS patient scale.

Main outcome measures were pathological results and operating time of procedures, estimated blood loss, preoperative and postoperative complications, and length of hospital stay between groups.

Statistical analyses

The IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22, was used for statistical analysis. Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Age, body mass index (BMI), operative time, blood loss, and hospital stay were compared using Student’s t-test for independent groups. Non-parametric categorical variables were compared with the Chi-square test; continuous variables were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. The criterion for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all comparisons.

| Results | ▴Top |

The study included a total of 132 patients: 62 patients in the MLS group and 70 patients in CLS group. Table 1 summarizes the comparison of a number of the demographic features between the groups. There was no difference between the two groups regarding preoperative diagnosis, intraoperative surgical procedure performed, and length of hospital stay. The groups were compared in terms of postoperative pathological diagnosis using the Chi-square test, and there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups. Comparing the operation time and hematocrit change, there were statistically significant differences between the two groups (Table 2). Both patient and observer PSOAS scar scores were better in MLS group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 1. Comparison of Demographical Features Between Groups |

Click to view | Table 2. Comparison of Operative Findings Between the Groups |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our results demonstrate that there were no significant differences between CLS group and MLS group in terms of surgery performed, duration of hospital stay, and intraoperative and postoperative complications. In our study, we found that operation time was longer in the MLS group. This is likely due to adaptation problems to surgical instruments in the beginning and unachievability to bipolar instruments in MLS that are commonly used in conventional laparoscopy for cutting and vessel stamping. As with all surgical procedures in minimally invasive surgery, the operation time may vary depending on several factors, such as physical characteristics of the patients (weight, surgical history, etc.), indication of the surgery, experience of the surgeon, technical features of the clinic, etc. In the literature, there are not many publications about MLS and the treatment of benign adnexal masses. Literature studies for mini-laparoscopy are mostly about pediatric and general surgery. A study regarding MLS for bening adnexal masses in the literature described longer operation time in this group [6]. We believe that our study has significance in this regard. Many surgeons believe that the performance debt of miniaturized instruments severely limits the applicability of the technique, and many are unwilling to endure the difficulties of using finer instruments without high-quality unbiased data to satisfactorily prove cogent benefit for patients. However, in the setting of general surgery, a meta-analysis has recently shown that mini-laparoscopy holds the advantage of eliciting a reduced level of wound pain compared with conventional laparoscopy, with better cosmetic results and decreased incisional hernia [7]. Ghezzi et al evaluated MLS in terms of hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy in different studies and reported that that is more advantageous [3, 8]. Fanfani et al reported that less port number and less port diameter are strongly related with less postoperative pain and require for analgesic [9]. Ardovino et al reported no difference in operation time and difficulty in surgery but they had better results about postoperative pain and cosmetic results [10]. Although evaluating of skin scar formation is challenged because of inadequate objective scales, majority of studies in the literature demonstrate that cosmetic results are better by using smaller trocar sizes [11-14]. We used both patient and observer scar scales for evaluation of scar formation. Both scores were better in MLS group than CLS group. Nowadays, according to patient preferences, especially for young patients, the cosmetic results of surgery are almost as important as to treatment of main pathology. We did not compare wound paining in this study, because our study was conducted retrospectively. By using mini-laparoscopy it can also be possible to reduce subcutaneus or subfacial bleeeding and hematoma formation [15]. The other advantage of mini-laparoscopy is reduction of the risk of postoperative hernia formation. It has shown that 86.3% of all trocar hernias occured with 12 mm or bigger trocars. Conversely, only 2.7% of all trocar hernias occured with 5 mm trochars. We feel that the vaginal incision is an advantage for tissue extraction and reducing incisional hernia risk. This allows the easy removal of specimens from the incision most of the time. In several cases, we utilized a 10 mm endo-bag to extract specimens. But it is a time consuming procedure compared to CLS. Unfortunately, MLS has certain disadvantages that may cause the prolonging of total operation time, suboptimal vision, loose grasping, weak manipulation defective irrigation or suction, difficulty during dissection and development of anatomical spaces and decreased instrument durability [4]. Nevertheless, several investigations in the field of gynecologic and non-gynecologic surgery suggest that downsizing abdominal ports allows equal or better surgical results compared with standard laparoscopic procedures [3, 16, 17]. In addition, the use of small-diameter laparoscopes and instruments was feasible with low carbon dioxide pressures [18], thereby reducing possible complications related to pneumoperitoneum. Some study limitations should be acknowledged such as the sample size and study desing (retrospectively). Despite these restraints, to the best of our knowledge, this represents the first study that compares MLS versus CLS for benign adnexal masses. Thus, further studies are necessary in this field.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Grant Support

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Medeiros LR, Stein AT, Fachel J, Garry R, Furness S. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for benign ovarian tumor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(3):387-399.

doi pubmed - Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R, van Voorst S, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD003677.

doi - Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Siesto G, Uccella S, Boni L, Serati M, Bolis P. Minilaparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy: results of a randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(4):455-461.

doi pubmed - Gagner M, Garcia-Ruiz A. Technical aspects of minimally invasive abdominal surgery performed with needlescopic instruments. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8(3):171-179.

doi pubmed - Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, Tuinebreijer WE, Middelkoop E, Kreis RW, van Zuijlen PP. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: a reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(7):1960-1965; discussion 1966-1967.

- Gencdal S, Aydogmus H, Aydogmus S, Ekmekci E, Kolsuz Z. Mini-Laparoscopic Surgery for Gynecological Conditions. SciTz Gynecol Reprod Med. 2016;1(1):1001.

- Sajid MS, Khan MA, Ray K, Cheek E, Baig MK. Needlescopic versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(6):437-442.

doi pubmed - Ghezzi F, Uccella S, Casarin J, Cromi A. Microlaparoscopic bilateral adnexectomy: a 3-mm umbilical port and a pair of 2-mm ancillary trocars served as conduits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(3):279 e271.

- Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Rossitto C, Gagliardi ML, Ercoli A, Gallotta V, Gueli Alletti S, et al. Laparoscopic, minilaparoscopic and single-port hysterectomy: perioperative outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(12):3592-3596.

doi pubmed - Ardovino M, Ardovino I, Castaldi MA, Trabucco E, Colacurci N, Cobellis L. Minilaparoscopic myomectomy: a mini-invasive technical variant. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23(10):871-875.

doi pubmed - Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Trap R, Kehlet H, Rosenberg J. Microlaparoscopic vs conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized double-blind trial. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(3):458-464.

doi pubmed - Novitsky YW, Kercher KW, Czerniach DR, Kaban GK, Khera S, Gallagher-Dorval KA, Callery MP, et al. Advantages of mini-laparoscopic vs conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2005;140(12):1178-1183.

doi pubmed - Schwenk W, Neudecker J, Mall J, Bohm B, Muller JM. Prospective randomized blinded trial of pulmonary function, pain, and cosmetic results after laparoscopic vs. microlaparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(4):345-348.

doi pubmed - Alponat A, Cubukcu A, Gonullu N, Canturk Z, Ozbay O. Is minisite cholecystectomy less traumatic? Prospective randomized study comparing minisite and conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomies. World J Surg. 2002;26(12):1437-1440.

doi pubmed - Nomura H, Okuda K, Saito N, Fujiyama F, Nakamura Y, Yamashita Y, Terai Y, et al. Mini-laparoscopic surgery versus conventional laparoscopic surgery for patients with endometriosis. Gynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy. 2013;2(85):e88.

doi - Liao CH, Lai MK, Li HY, Chen SC, Chueh SC. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy using needlescopic instruments for adrenal tumors less than 5cm in 112 cases. Eur Urol. 2008;54(3):640-646.

doi pubmed - Nicolay LI, Bowman RJ, Heldt JP, Jellison FC, Mehr N, Tenggardjaja C, Millard W, 2nd, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of traditional laparoendoscopic single-site surgery with needlescopic-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy in the porcine model. J Endourol. 2011;25(7):1187-1191.

doi pubmed - Bogani G, Uccella S, Cromi A, Serati M, Casarin J, Pinelli C, Ghezzi F. Low vs standard pneumoperitoneum pressure during laparoscopic hysterectomy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):466-471.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.