| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Case Report

Volume 8, Number 8, August 2016, pages 610-615

Convulsive Syncope Induced by Ventricular Arrhythmia Masquerading as Epileptic Seizures: Case Report and Literature Review

John Sabua, Kalyani Regetib, Mary Mallappallilc, John Kassotisd, Hamidul Islame, Shoaib Zafarb, Rafay Khanb, Hiyam Ibrahimb, Romana Kantab, Shuvendu Senb, Abdalla Yousifb, Qiang Naib, f

aDivision of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY 11203, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Raritan Bay Medical Center, Perth Amboy, NJ 08861, USA

cDivision of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY 11203, USA

dClinical cardiac electrophysiology, Department of Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY 11203, USA

eSayreville War Memorial High School, Parlin, NJ 08859, USA

fCorresponding Author: Qiang Nai, Department of Internal Medicine, Raritan Bay Medical Center, Perth Amboy, NJ 08861, USA. Current address: Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Toledo Medical Center, Toledo, OH 43614, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication May 25, 2016

Short title: Convulsive Syncope by Ventricular Arrhythmia

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2583w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

It is important but difficult to distinguish convulsive syncope from epileptic seizure in many patients. We report a case of a man who presented to emergency department after several witnessed seizure-like episodes. He had a previous medical history of systolic heart failure and automated implantable converter defibrillator (AICD) in situ. The differential diagnoses raised were epileptic seizures and convulsive syncope secondary to cardiac arrhythmia. Subsequent AICD interrogation revealed ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation (v-tach/fib). Since convulsive syncope and epileptic seizure share many similar clinical features, early diagnosis is critical for choosing the appropriate management and preventing sudden cardiac death in patients with presumed epileptic seizure.

Keywords: Syncope; Convulsion; Epilepsy; Seizure; Arrhythmia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Convulsive syncope and epileptic seizures can both cause transient loss of consciousness (LOC), but these two conditions are often difficult to distinguish. Syncope is the LOC and muscle tone due to reversible cerebral hypoperfusion. It is characterized by sudden onset, brevity, spontaneous and complete recovery. Epileptic seizure is the result of an abnormal, excessive and hypersynchronous neuronal in the brain [1-5]. The distinct pathophysiology underlying syncope and seizures necessitates different treatment and further prophylaxis strategies for each phenomenon. Therefore, it is fundamental to differentiate clearly between these two disorders before starting the appropriate intervention. We report a case of convulsive syncope mimicking epileptic seizures, and we further review the literature about diagnosing syncope and seizure.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 57-year-old man with previous medical history of hypertension, ventricular tachycardia storms, cardiac arrest, chronic systolic congestive heart failure (CHF) with ejection fraction (EF) of 10%, for which he had an AICD placed, chronic kidney disease, and anemia was brought to the emergency department after episodes of seizure-like activities at home. The patient’s wife witnessed the generalized physical shaking. The patient admitted experiencing a feeling of heat first, which drove him to the refrigerator for a cold drink. He then felt nauseous and lightheaded, fell into a chair, and subsequently passed out. Shortly after, tonic muscle activity with head and arm extension occurred and then myoclonic jerks of arms and legs started. At least two similar episodes occurred before the wife called emergency medical services (EMS). The episodes each lasted about 10 - 20 s, and the patient regained responsiveness in between, feeling short of breath, but without any pain. Patient underwent resuscitation by EMS at home and was then sent to the emergency department. There was tongue biting, without any eye rolling movement, urinary or bowel incontinence. The laboratory tests at admission are shown in Table 1 and further diagnostic tests are presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Click to view | Table 1. Laboratory Findings on Presentation |

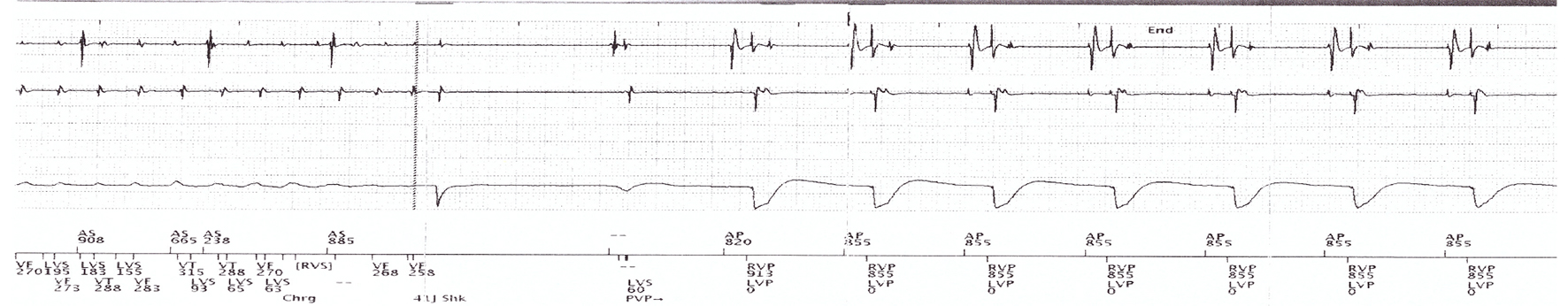

Click for large image | Figure 1. Copy of AICD interrogation showing the occurrence of V-tach/vib. The verical dash line indicates the shock. The trace shows the V-fib episode on the day of admission, which was promptly terminated by ICD. |

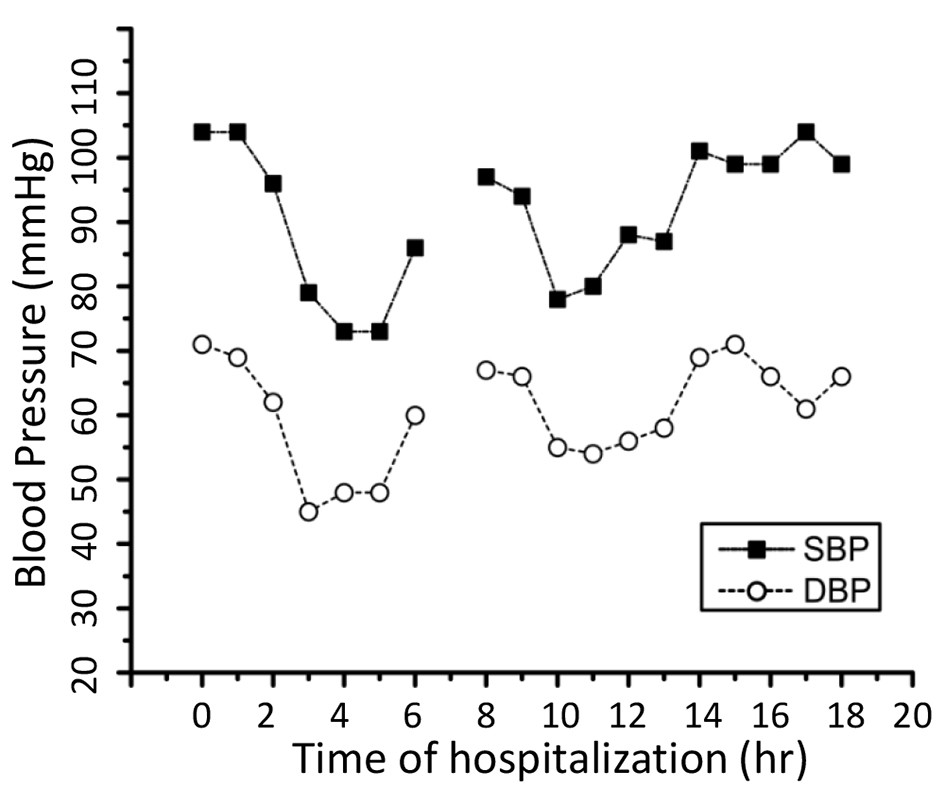

Click for large image | Figure 2. Blood pressure changes after admission. The heart function continued to worsen during this period as shown by the hypotensive episodes. Patient subsequently stabilized with appropriate medical treatment. |

The differential diagnosis raised was epileptic seizures versus generalized convulsion secondary to cardiogenic syncope. The cardiologist who had been working with this patient was called and the generalized seizure-like activities were then attributed to transient cerebral hypoperfusion secondary to cardiac arrhythmia. The patient was then admitted to coronary care unit (CCU), treated with amiodarone and electrolyte correction. Subsequent AICD interrogation revealed several corresponding episodes of ventricular-tachycardia and fibrillation (V-tack/fib). Patient experienced transient LOC during this period, but he eventually stabilized.

There were some overlapping clinical signs and symptoms that made the diagnosis difficult such as: 1) generalized myoclonic-like movement; 2) tongue biting; 3) repeated syncopal episodes in a short period. Supports for the diagnosis of convulsive syncope include the initial episode occurring at standing posture, limpness and failure of patient to respond occurring before the start of convulsion, each episode of LOC lasting less than a minute, that the patient regained consciousness between episodes of LOC and convulsion, and lastly prior presyncope symptoms.

| Discussion and Literature Review | ▴Top |

In order to develop the appropriate management plan and subsequent prophylaxis in patient with paroxysmal LOC, it is fundamental to differentiate between convulsive syncope and epileptic seizures. However, it is challenging to make the correct diagnosis due to a number of factors, such as overlapping clinical features, inadequate history, and limited investigations [1]. Both phenomena cause transient LOC, but with distinct pathophysiology. Briefly, syncope is LOC and muscle tone due to reversible cerebral hypoperfusion. It is characterized by sudden onset, lasting a few seconds, spontaneous and complete recovery [2-4]. There are different causes or types of syncope: 1) reflex (neurally)-mediated syncope, including vasovagal, situational syncope, and carotid sinus hypersensitivity, which is seen in young adults; 2) cardiac syncope due to arrhythmias, structural, or mechanical cardiac abnormalities, mostly seen in older adults; 3) orthostatic hypotension caused by autonomic dysfunction, medications, or hypovolemia, generally seen in the elderly; 4) cerebrovascular causes.

In contrast, an epileptic seizure has transient signs and symptoms caused by abnormal, excessive and synchronous discharge of neurons in the brain. Seizures, except status epilepticus, have clear onset and termination. However, the end of seizure may be blurred by the postictal state [5]. Epilepsy is characterized by enduring alteration in the brain that increases the likelihood of recurrent seizures, and is associated with neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences. At least one seizure is required for the diagnosis of epilepsy [5, 6].

An unexpectedly high frequency (20-30%) of the misdiagnosis of epilepsy has been reported by different studies, wherein cardiovascular syncope was the most commonly misdiagnosed condition [7-14]. This is most likely due to confounding factors including overlapping clinical features, incomplete history-taking, misinterpretation of electroencephalography (EEG) and neuroimaging results, and the experience of physicians [9, 13, 15, 16]. It is therefore essential that attention should be paid to possible cardiovascular causes in patients presenting with seizure-like symptoms.

The consequences of misdiagnosis of epilepsy (seizure) are multifold. Firstly, it may delay the proper treatment and prophylaxis or syncope, lead to unnecessary medications or procedures, and cause unexpected complication and sudden death [17, 18]. Secondly, misdiagnosis and consequent management may cause adverse effects. Several anticonvulsant medications have been reported to have cardiotoxicity. Pregabalin has been related to heart failure [19], oxcarbazepine was reported to induce resistant V-fib [20], and carbamazepine can cause atrioventricular (AV) block [21, 22], hypotension [23] or hypertension [24], and bradycardia [25]. Those side effects may further deteriorate the cardiac function. Furthermore, it causes negative psychological and socio-economic impacts on patients, and substantially increases economic burden on the health and welfare services.

On the other hand, appropriate management produces favorable long-term outcome. Amiodarone has been reported to provide effective prophylaxis against certain cardiac conditions such as V-fib [26]. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) have been shown to provide greater reduction in mortality compared to medical treatment with antiarrhythmic drug therapy (amiodarone, metoprolol, and propafenone) in survivors of cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular arrhythmias [27-29]. ICDs have been reported to be safe and highly effective in primary and secondary prevention of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [28]. Therefore, rapid and accurate diagnosis of convulsive syncope is of vital importance in guiding the appropriate treatment and significantly improves prognosis.

Several excellent articles have provided valuable information about diagnosing syncope and seizure [13, 30-33]. A detailed history from patients and witnesses, physical examination, and ECG produce combined diagnostic yield of 50%, and are indispensable in the diagnosis of convulsive syncope and seizure [15, 17, 32, 34-36]. A thorough history can often provide the most important information in diagnosis of syncope. It should focus on signs and symptoms before, during, and after the spells, such as postural symptoms (vasovagal or orthostatic syncope); exertional symptoms (cardiac syncope); situational symptoms (defecation or micturition), and medications such as antihypertensive drugs. Acknowledgement of relevant risk factors also helps in the evaluation, such as existing electrical and structural heart disease, and positive family history including prolonged QT syndrome [32, 36]. Some clinical features that may help establish initial diagnosis of syncope and seizures are listed in Table 2 [13, 15, 30, 31, 34, 37, 38]. In order to facilitate the diagnosis of syncope and seizure, a simple point score based solely on historical features was proposed [32]. This point score distinguishes syncope from seizure with 94% sensitivity and 94% specificity (Table 3 [32]). In addition, clinical history also helps to further distinguish syncope due to V-tach from vasovagal syncope [39]. For example, six features were found to be significant predictors. Syncope due to V-tach can be predicted by: 1) male gender and 2) age of first onset > 35 years, while vasovagal syncope can be predicted by: 1) prolonged sitting or standing; 2) presyncope preceded by stress; 3) recurrent headaches; and 4) fatigue lasting longer than 1 min after syncope. Physical findings useful in the diagnosis include orthostatic hypotension, cardiovascular and neurologic signs [35]. Although ECG alone helps determine the cause of syncope in 5% of cases, it is risk free and inexpensive; and findings such as bundle-branch block, non-sustained V-tach, previous myocardial infarction, and left ventricular hypertrophy may help guide further evaluation; it is recommended in almost all syncopal patients [35].

Click to view | Table 2. Characteristics of Syncope Versus Seizures (Adapted From [13, 15, 30, 31, 34, 37, 38]) |

Click to view | Table 3. Questions Help to Distinguish Syncope From Seizure (Adapted From [32]) |

A number of advanced diagnostic tests can provide additional hints in the assessment of doubtful cases, such as head-up tilt table testing, Holter monitoring or telemetry, implantable loop recorder, echocardiogram, ischemia evaluation/stress testing, electrophysiological studies (EPS), carotid sinus massage, CT/MRI, EEG, simultaneous EEG and ECG, prolactin and creatinine kinase, and diagnostic questionnaire [1, 36, 40-44]. Among these, the clinical history, physical examination, ECG, and head-up tilt test are the most important tools for young patients, while in the higher age group, EPS with pharmacological stress testing and carotid sinus massage become more important; echocardiography and exercise testing should be used for the initial investigation searching for underlying structural heart diseases [30].

At last, it would be worth mentioning the complicated brain-heart interaction, which creates even more diagnostic challenges and increases confusion. Although it is rare, the interaction between syncope and epileptic seizure in the same attack has been reported, as well as that they may provoke each other [31]. Cardiac arrhythmias sometimes coincide with epileptic seizures, the arrhythmias may precede seizure [42, 45], or in some other cases, seizures precede cardiac arrhythmia, such as ictal sinus tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, bradycardia and asystole [46-49]. The ictal bradycardia, which occurs when epileptic discharges markedly disrupt normal cardiac rhythm, may lead to cardiogenic syncope [50]. Some individuals may have both components of syncope and epilepsy, therefore treatment aimed at both cardiac and neurological aspects is needed [37]. Interestingly, some mutations of ion channels were found in both heart and brain, leading to susceptibility to both epilepsy and arrhythmia [51-54].

Briefly, the management of patients who experience TLOC with convulsion requires careful history and physical examination, and sometimes additional diagnostic tests; it also needs the cooperation between different clinical specialties such as cardiology and neurology.

| References | ▴Top |

- Grubb BP, Gerard G, Roush K, Temesy-Armos P, Elliott L, Hahn H, Spann C. Differentiation of convulsive syncope and epilepsy with head-up tilt testing. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(11):871-876.

doi pubmed - Ariturk Z, Alici H, Cakici M, Davutoglu V. A rare cause of syncope: cough. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(Suppl 1):71-72.

pubmed - van Dijk JG, Wieling W. Pathophysiological basis of syncope and neurological conditions that mimic syncope. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55(4):345-356.

doi pubmed - van Dijk JG, Thijs RD, Benditt DG, Wieling W. A guide to disorders causing transient loss of consciousness: focus on syncope. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(8):438-448.

doi pubmed - Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, Engel J, Jr. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia. 2005;46(4):470-472.

doi pubmed - Engel J, Jr. A proposed diagnostic scheme for people with epileptic seizures and with epilepsy: report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2001;42(6):796-803.

doi pubmed - Akhtar MJ. All seizures are not epilepsy: many have a cardiovascular cause. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52(3):116-120.

pubmed - Chowdhury FA, Nashef L, Elwes RD. Misdiagnosis in epilepsy: a review and recognition of diagnostic uncertainty. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(10):1034-1042.

doi pubmed - Fattouch J, Di Bonaventura C, Strano S, Vanacore N, Manfredi M, Prencipe M, Giallonardo AT. Over-interpretation of electroclinical and neuroimaging findings in syncopes misdiagnosed as epileptic seizures. Epileptic Disord. 2007;9(2):170-173.

pubmed - Josephson CB, Rahey S, Sadler RM. Neurocardiogenic syncope: frequency and consequences of its misdiagnosis as epilepsy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007;34(2):221-224.

doi pubmed - Scheepers B, Clough P, Pickles C. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy: findings of a population study. Seizure. 1998;7(5):403-406.

doi - Schott GD, McLeod AA, Jewitt DE. Cardiac arrhythmias that masquerade as epilepsy. Br Med J. 1977;1(6074):1454-1457.

doi pubmed - Smith D, Defalla BA, Chadwick DW. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy and the management of refractory epilepsy in a specialist clinic. QJM. 1999;92(1):15-23.

doi pubmed - Zaidi A, Clough P, Cooper P, Scheepers B, Fitzpatrick AP. Misdiagnosis of epilepsy: many seizure-like attacks have a cardiovascular cause. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(1):181-184.

doi - Kowacs PA, Silva Junior EB, Santos HL, Rocha SB, Simao C, Meneses MS, Arruda WO. Syncope or epileptic fits? Some examples of diagnostic confounding factors. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005;63(3A):597-600.

doi pubmed - van Donselaar CA, Stroink H, Arts WF. How confident are we of the diagnosis of epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2006;47(Suppl 1):9-13.

doi pubmed - Linzer M, Grubb BP, Ho S, Ramakrishnan L, Bromfield E, Estes NA, 3rd. Cardiovascular causes of loss of consciousness in patients with presumed epilepsy: a cause of the increased sudden death rate in people with epilepsy? Am J Med. 1994;96(2):146-154.

doi - Rutter N, Southall DP. Cardiac arrhythmias misdiagnosed as epilepsy. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60(1):54-56.

doi pubmed - Erdogan G, Ceyhan D, Gulec S. Possible heart failure associated with pregabalin use: case report. Agri. 2011;23(2):80-83.

pubmed - El-Menyar A, Khan M, Al Suwaidi J, Eljerjawy E, Asaad N. Oxcarbazepine-induced resistant ventricular fibrillation in an apparently healthy young man. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(6):693 e691-693.

- Ide A, Kamijo Y. Intermittent complete atrioventricular block after long term low-dose carbamazepine therapy with a serum concentration less than the therapeutic level. Intern Med. 2007;46(9):627-629.

doi pubmed - Takayanagi K, Hisauchi I, Watanabe J, Maekawa Y, Fujito T, Sakai Y, Hoshi K, et al. Carbamazepine-induced sinus node dysfunction and atrioventricular block in elderly women. Jpn Heart J. 1998;39(4):469-479.

doi pubmed - Tibballs J. Acute toxic reaction to carbamazepine: clinical effects and serum concentrations. J Pediatr. 1992;121(2):295-299.

doi - Marini AM, Choi JY, Labutta RJ. Transient neurologic deficits associated with carbamazepine-induced hypertension. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26(4):174-176.

doi pubmed - Kasarskis EJ, Kuo CS, Berger R, Nelson KR. Carbamazepine-induced cardiac dysfunction. Characterization of two distinct clinical syndromes. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(1):186-191.

doi pubmed - Tsai CF, Chen SA, Tai CT, Chiang CE, Ding YA, Chang MS. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation: clinical, electrophysiologic characteristics and long-term outcomes. Int J Cardiol. 1998;64(1):47-55.

doi - Kuck KH, Cappato R, Siebels J, Ruppel R. Randomized comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest : the Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg (CASH). Circulation. 2000;102(7):748-754.

doi pubmed - Maron BJ, Spirito P. Implantable defibrillators and prevention of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(10):1118-1126.

doi pubmed - Siebels J, Kuck KH. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator compared with antiarrhythmic drug treatment in cardiac arrest survivors (the Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg). Am Heart J. 1994;127(4 Pt 2):1139-1144.

doi - Bergfeldt L. Differential diagnosis of cardiogenic syncope and seizure disorders. Heart. 2003;89(3):353-358.

doi pubmed - Lempert T. Recognizing syncope: pitfalls and surprises. J R Soc Med. 1996;89(7):372-375.

pubmed - Sheldon R, Rose S, Ritchie D, Connolly SJ, Koshman ML, Lee MA, Frenneaux M, et al. Historical criteria that distinguish syncope from seizures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(1):142-148.

doi - Strickberger SA, Benson DW, Biaggioni I, Callans DJ, Cohen MI, Ellenbogen KA, Epstein AE, et al. AHA/ACCF scientific statement on the evaluation of syncope: from the American Heart Association Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Stroke, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and the American College of Cardiology Foundation In Collaboration With the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(2):473-484.

doi pubmed - Hoefnagels WA, Padberg GW, Overweg J, van der Velde EA, Roos RA. Transient loss of consciousness: the value of the history for distinguishing seizure from syncope. J Neurol. 1991;238(1):39-43.

doi pubmed - Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NA, 3rd, Wang P, Vorperian VR, Kapoor WN. Diagnosing syncope. Part 1: Value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(12):989-996.

doi pubmed - Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NA, 3rd, Wang P, Vorperian VR, Kapoor WN. Diagnosing syncope. Part 2: Unexplained syncope. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(1):76-86.

doi pubmed - Rodrigues Tda R, Sternick EB, Moreira Mda C. Epilepsy or syncope? An analysis of 55 consecutive patients with loss of consciousness, convulsions, falls, and no EEG abnormalities. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33(7):804-813.

doi pubmed - Duplyakov D, Golovina G, Garkina S, Lyukshina N. Is it possible to accurately differentiate neurocardiogenic syncope from epilepsy? Cardiol J. 2010;17(4):420-427.

pubmed - Sheldon R, Hersi A, Ritchie D, Koshman ML, Rose S. Syncope and structural heart disease: historical criteria for vasovagal syncope and ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21(12):1358-1364.

doi pubmed - Fernandez Sanmartin M, Rodriguez Nunez A, Martinon-Torres F, Eiris Punal J, Martinon Sanchez JM. [Convulsive syncope: characteristics and reproducibility using the tilt test]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2003;59(5):441-447.

doi - Gauer RL. Evaluation of syncope. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(6):640-650.

pubmed - Howell SJ, Blumhardt LD. Cardiac asystole associated with epileptic seizures: a case report with simultaneous EEG and ECG. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52(6):795-798.

doi - Nousiainen U, Mervaala E, Uusitupa M, Ylinen A, Sivenius J. Cardiac arrhythmias in the differential diagnosis of epilepsy. J Neurol. 1989;236(2):93-96.

doi pubmed - Palaniswamy C, Aronow WS, Agrawal N, Balasubramaniyam N, Lakshmanadoss U. Syncope: Approaches to Diagnosis and Management. Am J Ther. 2016;23(1):e208-217.

doi pubmed - Pacia SV, Devinsky O, Luciano DJ, Vazquez B. The prolonged QT syndrome presenting as epilepsy: a report of two cases and literature review. Neurology. 1994;44(8):1408-1410.

doi pubmed - Devinsky O, Pacia S, Tatambhotla G. Bradycardia and asystole induced by partial seizures: a case report and literature review. Neurology. 1997;48(6):1712-1714.

doi pubmed - Ferlisi M, Tomei R, Carletti M, Moretto G, Zanoni T. Seizure induced ventricular fibrillation: a case of near-SUDEP. Seizure. 2013;22(3):249-251.

doi pubmed - Lanz M, Oehl B, Brandt A, Schulze-Bonhage A. Seizure induced cardiac asystole in epilepsy patients undergoing long term video-EEG monitoring. Seizure. 2011;20(2):167-172.

doi pubmed - Rocamora R, Kurthen M, Lickfett L, Von Oertzen J, Elger CE. Cardiac asystole in epilepsy: clinical and neurophysiologic features. Epilepsia. 2003;44(2):179-185.

doi pubmed - Reeves AL, Nollet KE, Klass DW, Sharbrough FW, So EL. The ictal bradycardia syndrome. Epilepsia. 1996;37(10):983-987.

doi pubmed - Emmi A, Wenzel HJ, Schwartzkroin PA, Taglialatela M, Castaldo P, Bianchi L, Nerbonne J, et al. Do glia have heart? Expression and functional role for ether-a-go-go currents in hippocampal astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2000;20(10):3915-3925.

pubmed - Hartmann HA, Colom LV, Sutherland ML, Noebels JL. Selective localization of cardiac SCN5A sodium channels in limbic regions of rat brain. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(7):593-595.

doi pubmed - Johnson JN, Hofman N, Haglund CM, Cascino GD, Wilde AA, Ackerman MJ. Identification of a possible pathogenic link between congenital long QT syndrome and epilepsy. Neurology. 2009;72(3):224-231.

doi pubmed - Nashef L, Walker F, Allen P, Sander JW, Shorvon SD, Fish DR. Apnoea and bradycardia during epileptic seizures: relation to sudden death in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;60(3):297-300.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.