| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Case Report

Volume 6, Number 2, April 2014, pages 153-155

Chronic Abdominal Pain Secondary to Mesh Erosion Into Ceacum Following Incisional Hernia Repair: A Case Report and Literature Review

Fahad Aziza, c, Misbah Zaeemb

aPenn State Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, MC, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

bWake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

cCorresponding author: Fahad Aziz, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, MC, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication January 03, 2014

Short title: Chronic Abdominal Pain

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr1730w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Incisional hernias following abdominal operations are a common complication. Mesh is frequently employed in repair of these hernias. Mesh migration is an infrequent occurrence. We present the case of transmural mesh migration from the abdominal wall into the ceacum presenting as chronic abdominal pain. Given the popularity of minimally invasive surgery utilizing polypropylene mesh for incisional hernia repair, related complications such as postoperative hematoma and seroma, foreign body reaction, organ injury, infection, mesh rejection and fistula are increasingly being noted. Most of the mesh migrations reported in the literature involve the urinary bladder. We present a case of delayed mesh migration into the ceacum. Mesh migration is a rare and peculiar complication that is rarely reported in the literature. A review of the literature shows that there are no other cases of mesh migration into ceacum several years after open type incisional hernia repair.

Keywords: Hernioplasty complication; Mesh migration; Ceacum erosion; Chronic abdominal pain

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Incisional hernia is the most common complication of abdominal surgery, with incidence up to 10-15% and recurrence rates of 20-45% [1, 2]. These hernias are often repaired with synthetic mesh to reinforce the repair or to reduce tension on weakened or missing abdominal wall fascia. This case represents one unusual complication of using mesh. Mesh migration is an infrequent occurrence. The offending lesion was found to be the prolene mesh having eroded into the ceacum. The migration of mesh into the ceacum was likely the result of several unusual events: polypropylene stitches migrating through the abdominal wall, mesh freely moving in the abdominal cavity and complete erosion through the ceacum into the lumen. Technical factors as well as patient factors are likely involved in these cases. Due to the rare nature of these events, it is unclear whether type of mesh or type of fixation played a role in mesh migration into bowel. Mesh migration has rarely been reported.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

The patient is a 56-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension and fibroids. She had multiple abdominal surgeries including two cesarean sections and total abdominal hysterectomy. Five months later after her last surgery, the patient presented with a large incisional abdominal hernia. She had hernia repair with polypropylene mesh under general anesthesia. Her postoperative course was uncomplicated.

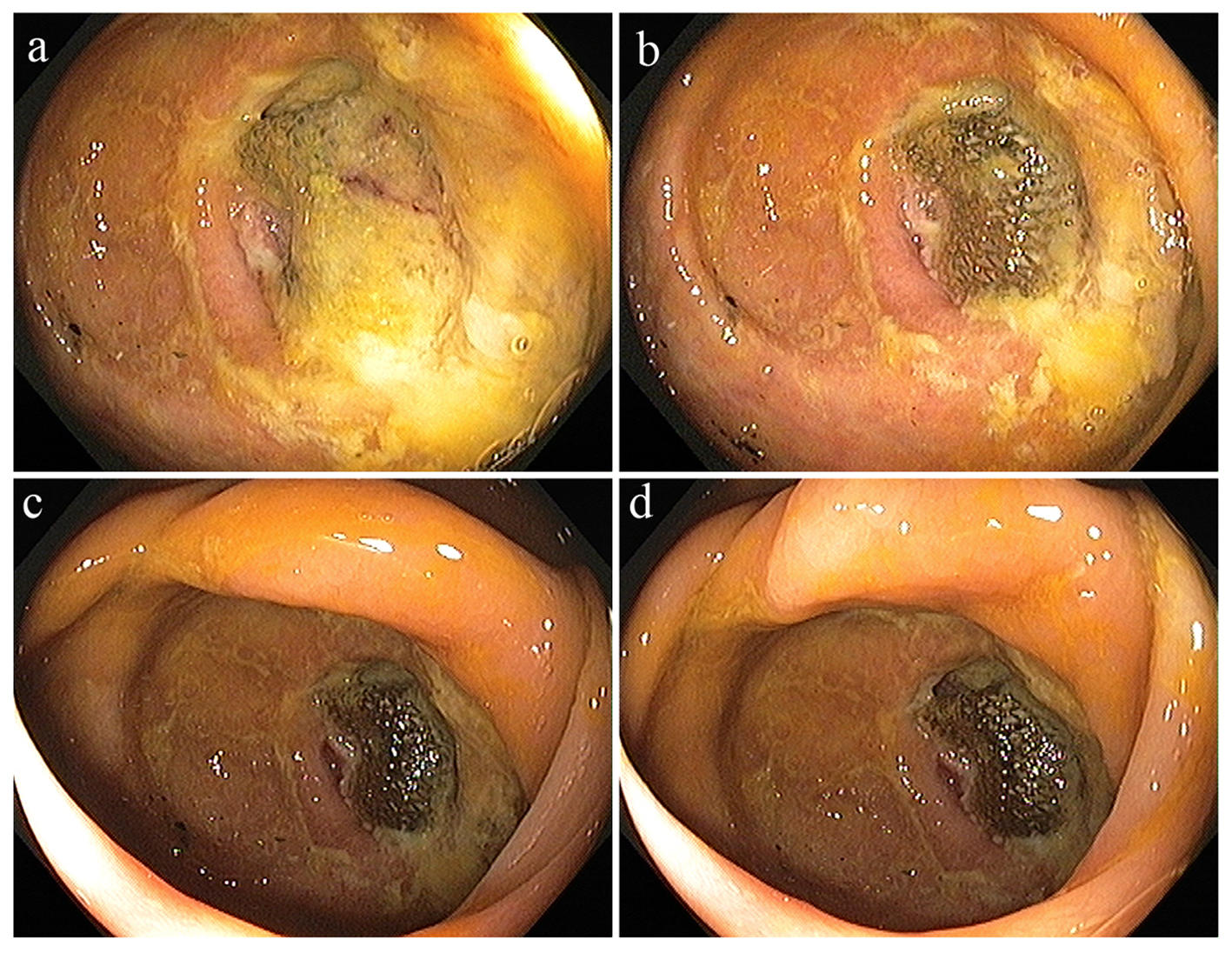

Approximately 14 years after hernia repair, the patient presented to the emergency department with the complaints of intermittent, abdominal pain, starting at right lower quadrant and migrating upwards to all over abdomen, associated with episodes of nausea. She had this pain from the 2 years prior to the presentation, which had been getting worse. She denied any other complaints. She had good bowel sounds on the physical examination. All lab work was unremarkable. Computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen and pelvis was also unremarkable. She got colonoscopy as part of regular screening process which showed diffuse diverticulosis and a foreign body in the cecum (Fig. 1). In light of the patient’s past history of incisional hernia repair, the foreign body was consistent with migration of previous surgical mesh into the ceacum.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a-d) Diffuse diverticulosis and a foreign body in the cecum. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The use of metallic mesh to reinforce the approximated tissues of a hernia repair or to actually replace the defect developed widespread use by 1946. An increase in wound complications, such as serum accumulations, wound infections and persistent draining sinuses resulted from the use of tantalum or stainless steel mesh. Consequently, the use of tantalum or stainless steel mesh, whole skin and cutis was completely abandoned by 1970 [2]. A knitted polypropylene mesh (Marlex) introduced in 1959 and expanded polytetra fluoro-ethylene patch (Gortex) have been increasingly used in hernia repairs over the past three decades. Use of fascia lata, while still an excellent alternative to synthetic material in specific cases, has significantly declined in hernia repairs.

Mesh repairs minimize the amount of tension that must be put on the abdominal wall in order to cover the hernia, and are generally considered preferable for incisional hernias. In a long-term retrospective study from Europe, the incidence of recurrence of incisional hernias after simple sutured repair was over 60%; the use of mesh decreased the recurrence rate to approximately 30% [3-5]. Mesh repair is particularly important for incisional hernias with a diameter greater than 4 cm as the risk of recurrence is likely related to the tension placed on the repair in large hernias. Since then, many types of mesh have been developed. Complications related to the use of artificial materials in hernia repair include postoperative hematoma and seroma, foreign body reaction, organ injury, infection, mesh rejection and fistula. Mesh migration following hernia repair is an uncommon complication. Erosion into a viscous can be associated with migration or can occur with the mesh in the intended position.

When this occurs, infection, abscess, fistula, or obstructions are the most common sequelae. Migration to a completely intra-luminal position is exceedingly rare. Mesh migration occurs generally through two mechanisms. Primary mechanical migration occurs when an inadequately secured mesh traverses along adjoining paths of least resistance or when a relatively secure mesh is displaced by external forces [1]. Secondary migration, on the other hand, occurs through trans-anatomical planes and is the result of erosions triggered by foreign body reaction [6, 7]. This mechanism has been supported by the presence of inflammatory granulation tissue at the site of migration. The latter process is gradual and may take several years [8].

Mesh migration is rare and unpredictable. Clinical presentations are variable and related to the organ involved. Migration of mesh into the urinary bladder has been reported to cause hematuria and recurrent urinary tract infections [9]. One report noted mesh migration into the scrotum after laparoscopic hernia repair that presented as a tender scrotal mass [10]. In another report of scrotal migration of mesh, strangulating bowel obstruction was the presenting feature [11]. Several reports of resultant enteric and enterovesical fistulas have been reported [12-14]. More ominous findings such as bowel obstruction and sigmoid perforation have also been documented [15-17]. Successful colonoscopic removal of a migrated mesh from the colon at the splenic flexure has also been reported. After a literature review discussing the significant complications that result from mesh migration, the authors hypothesize that the method of fixation, as well as type of mesh, may have contributed to this problem.

The method of fixation may affect migration rates by altering the tensile strength and degree of movement of the mesh. The nature of the biomaterial is also important, as it affects the extent and degree of interaction with the surrounding tissue [18]. The size, shape and positioning of the mesh may also be significant. One study, in particular, showed that new low-weight mesh shows significantly less cellular proliferation and foreign body reaction than traditional prolene mesh. Biologic agents are being used with increasing frequency in abdominal wall hernias, where they have been shown to decrease foreign body reaction and potential infectious complications. There are one to two case reports of mesh migration into small bowel, bladder, large bowel, ceacum, but all after laparoscopic inguinal hernia and this is first case after open incisional hernia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, mesh migration, particularly erosion, is a rare complication of any incisional hernia repair, especially following total extraperitoneal repair. There is no clear cause of this complication, but new methods of mesh fixation, as well as types of mesh, are being investigated. It should also be recognized that mesh complications, particularly erosion, tend to occur years later and should be considered in atypical patient presentations. If tissue is available to place between the mesh and bowel so that they are not in direct contact, this might help avoid this complication.

Given the popularity of these surgical procedures, complications may be frequently encountered; gastroenterologists should thus be aware of the potential complications and the appropriate management.

| References | ▴Top |

- Mudge M, Hughes LE. Incisional hernia: a 10 year prospective study of incidence and attitudes. Br J Surg. 1985;72(1):70-71.

pubmed - Kingsnorth A, LeBlanc K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet. 2003;362(9395):1561-1571.

pubmed - Burger JW, Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, Halm JA, Verdaasdonk EG, Jeekel J. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg. 2004;240(4):578-583, discussion 583-575.

pubmed - Flum DR, Horvath K, Koepsell T. Have outcomes of incisional hernia repair improved with time?A population-based analysis. Ann Surg. 2003;237(1):129-135.

pubmed - Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, van den Tol MP, de Lange DC, Braaksma MM, JN IJ, Boelhouwer RU,

et al . A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(6):392-398.

pubmed - Agrawal A, Avill R. Mesh migration following repair of inguinal hernia: a case report and review of literature. Hernia. 2006;10(1):79-82.

pubmed - Yolen SR, Grossman ET. Colonoscopic removal of a postoperative foreign body. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11(4):483.

pubmed - Ojo P, Abenthroth A, Fiedler P, Yavorek G. Migrating mesh mimicking colonic malignancy. Am Surg. 2006;72(12):1210-1211.

pubmed - Hume RH, Bour J. Mesh migration following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1996;6(5):333-335.

pubmed - van Ophoven A, deKernion JB. Clinical management of foreign bodies of the genitourinary tract. J Urol. 2000;164(2):274-287.

pubmed - Maier U, Treu TM. Bladder stone as a rare complication one year after laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. Surgery. 1996;119(1):110-111.

pubmed - Dieter RA, Jr. Mesh plug migration into scrotum: a new complication of hernia repair. Int Surg. 1999;84(1):57-59.

pubmed - Nowak DD, Chin AC, Singer MA, Helton WS. Large scrotal hernia: a complicated case of mesh migration, ascites, and bowel strangulation. Hernia. 2005;9(1):96-99.

pubmed - Murphy JW, Misra DC, Silverglide B. Sigmoid colonic fistula secondary to Perfix-plug, left inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. 2006;10(5):436-438.

pubmed - Gray MR, Curtis JM, Elkington JS. Colovesical fistula after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 1994;81(8):1213-1214.

pubmed - Rieger N, Brundell S. Colovesical fistula secondary to laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal polypropylene (TAPP) mesh hernioplasty. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(1):218-219.

pubmed - Chuback JA, Singh RS, Sills C, Dick LS. Small bowel obstruction resulting from mesh plug migration after open inguinal hernia repair. Surgery. 2000;127(4):475-476.

pubmed - Ferrone R, Scarone PC, Natalini G. Late complication of open inguinal hernia repair: small bowel obstruction caused by intraperitoneal mesh migration. Hernia. 2003;7(3):161-162.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.