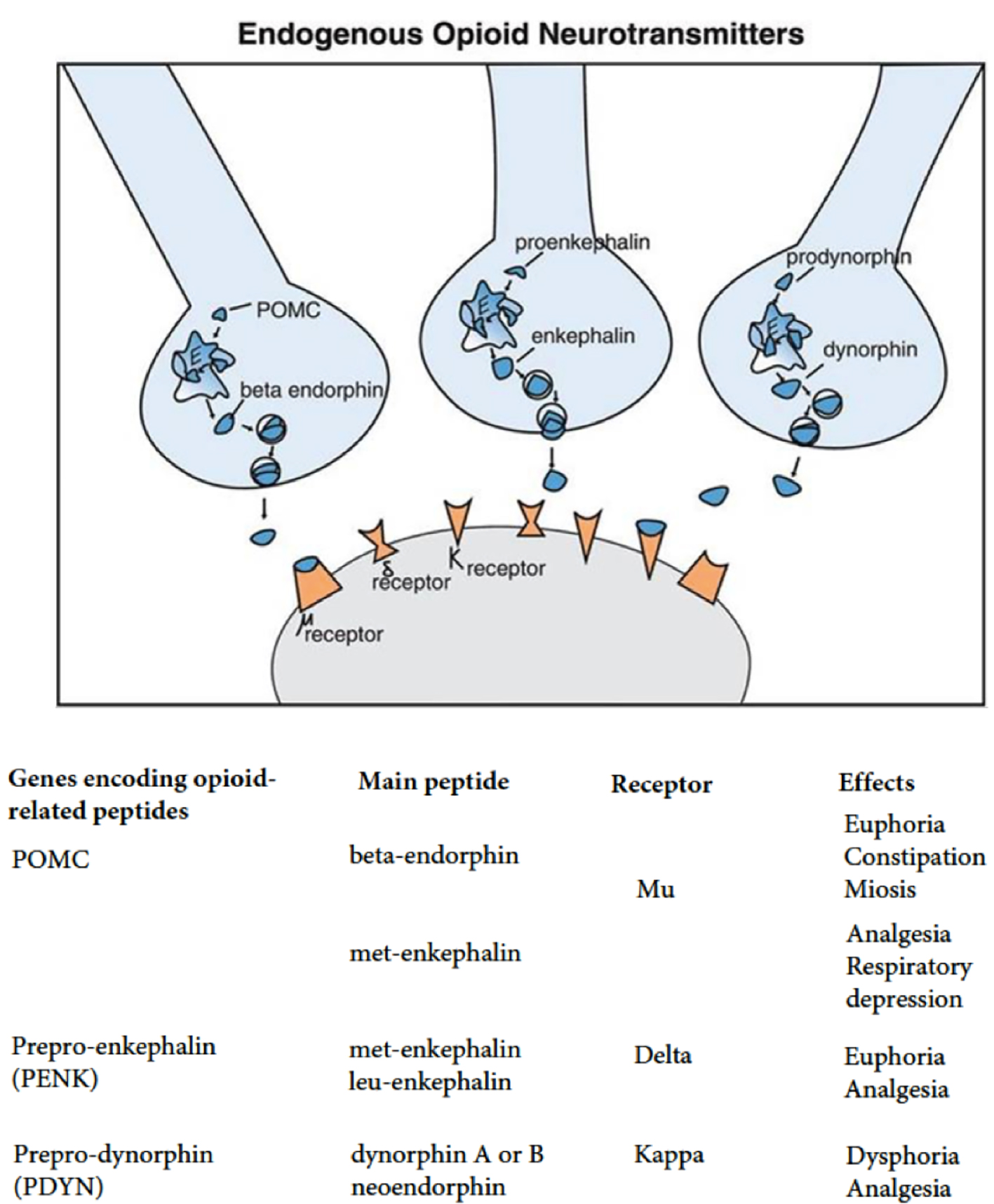

Figure 1. Endogenous opioid neurotransmitters. MOR: mu-opioid receptor; DOR: delta-opioid receptor; KOR: kappa-opioid receptor; OPRM1: opioid receptor mu 1; OPRD1: opioid receptor delta 1; OPRK1: opioid receptor kappa 1.

| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jocmr.org |

Review

Volume 12, Number 2, February 2020, pages 41-63

The Opioid System and Food Intake: Use of Opiate Antagonists in Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder and Abnormal Eating Behavior

Figures

Tables

| Chemical name | Affinity to receptors | Method of application | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naloxone | (5 alpha)-4.5-epoxy-3.14-dihydroxy-17-(2-propenyl)morphinan-6-on | Possesses highest affinity to µ-receptors and lesser affinity to κ- and δ-opioid receptors | Parenteral, intravenous and intramuscular |

| Naltrexone | (5 alpha)-17- (cyclopropyl methyl)-4.5-epoxy-3.14-dihydroxy morphinan-6-on | 0.26 nM to µ-receptors, 5.15 nM to κ-receptors and 117 nM to δ-receptors | Injections or capsules for implantation |

| Nalmefene | 17-cyclopropyl methyl-4.5α-epoxy-6-methylmorphinan-3.14-diol | 0.08 nM to κ-receptors and 0.24 nM to µ-receptors | Parenteral or oral |

| References | Description of study | Medications | Dosages | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bertino et al (1991) [17] | Randomized controlled double-blind study, involving 18 male college students. The objective was to test reduction in intake of food with administration of naltrexone | Naltrexone | 50 mg administered once daily in tablet form | Reduction in intake of food after administration of naltrexone |

| Billes (2014) [25] | Systematic review of literature assessing effectiveness of combining naltrexone and bupropion in promoting weight loss | Naltrexone and bupropion | 8 mg of naltrexone + 90 mg of bupropion | Profound and sustained reduction in weight loss |

| Drewnowski et al (1995) [23] | Randomized controlled double-blind study assessing effects of naloxone on food consumption | Naloxone | 6 mg bolus followed by a 0.1 mg per kg every hour, administered intravenously for 2.5 h | Reduction in binge eating habits but no significant effect on weight loss |

| Holtzman (1979) [24] | Randomized controlled trial involving rats. The objective was to determine effect of naloxone in suppressing eating and drinking habits | Naloxone | 0.3 - 10 mg/kg administered intravenously | Suppression of eating and drinking in a dose-related manner |

| Kumar and Aronne (2017) [29] | Book section discussing pharmacotherapy for obesity | Combination of naltrexone and bupropion | Naltrexone 32 mg and bupropion 360 mg | Significant weight loss when combined with lifestyle modification |

| Lee and Fujioka (2009) [27] | Extensive systematic review of literature to assess use of naltrexone in treatment of obesity | Naltrexone | 50 mg tablet | Monotherapy is associated with insignificant loss of weight |

| Malcolm et al (1985) [28] | Randomized controlled trial assessing effectiveness of naltrexone in obesity reduction. The trial was carried out for 10 weeks and involved 14 subjects who were male and 27 subjects who were female. A placebo was used for the control group | Naltrexone | Daily dosage of 200 mg | No significant reduction in body weight |

| Mason et al (2015) [37] | Randomized controlled trial | Naltrexone | 25 mg on day 1 followed by 50 mg daily for 2 days | Reduction in reward-driven eating and craving for food |

| Moore et al (1981) [21] | Randomized controlled trial. They sampled 12 female patients who were suffering from anorexia nervosa who were in the inpatient unit of a hospital. These subjects were between the age of 16 years and 38 years, with 37.6 kg as their mean weight. They were subjected to a regimen characterized with punishment and reward, with the inclusion of amitriptyline for treating depression after being admitted at the hospital for a period not less than 2.9 weeks; the subjects were given naloxone through intravenous infusion. Administration of naloxone was continued for 5 weeks, on average. Two of these participants were given normal saline intravenously as a placebo one week prior and a week after infusion with naloxone. Per study protocol, their blood was tested | Naloxone | Initial dose ranged between 1.0 mg every 12 h and 3.2 mg, increased after week 1 to between 3.2 mg and 6.4 mg | Naloxone had antilipolytic effect that was responsible for weight gaining |

| Rebello and Greenway (2016) [36] | Systematic literature review | Naltrexone and bupropion combination | 32 mg/360 mg | Reduction in frequency and strength of cravings for food |

| Selleck and Baldo (2017) [30] | Systematic literature review: prefrontal cortex-based opioid effects were compared to those elicited from the NAcc, to glean possible common functional principles; the motivational effects of opiates were discussed | Eating was induced by action of opioids in prefrontal cortex and NAcc through enhancement of reactivity to taste | ||

| Sinclair (2006) [19] | Patent on use of naloxone to treat eating disorders | Naloxone | Reduction in bulimia | |

| Stolar (1988) [20] | Chapter overview on effects of naloxone on eating disorders like hyperphagia | Naloxone | Reduction of severity of hyperphagia | |

| Yeomans and Gray (1996) [31] | A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study to determine effects that naltrexone has on intake of food and its pleasantness | Naltrexone | 50 mg of naltrexone | The amount of food intake reduced but sweetness and saltiness of food was not affected by naltrexone |

| Giuliano et al (2012) [26] | In-lab study on rats | GSK1521498 Naltrexone | GSK1521498 (0.1, 1 and 3 mg/kg) or naltrexone (NTX, 0.1, 1 and 3 mg/kg) | Both compounds reduced binge-like palatable food hyperphagia. Reduced food-seeking behavior |

| Yanovski and Yanovski (2015) [32] | Review article | Naltrexone-extended release plus bupropion -extended release (NB) (brand name, Contrave) | This preparation consists of a combination of 360 mg of bupropion and 32 mg of naltrexone | Preparation is effective and FDA-approved for adults with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or with BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 plus obesity-related comorbidities |

| Behavioral weight loss therapy | Treatment that incorporates various behavioral strategies, such as caloric restriction and increased physical activity, to promote weight loss |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) | Psychotherapy that focuses on identifying relathionships among thoughts, feelings and behaviors and aims to change patients’ negative thoughts about themselves and the world and, by doing so, reduce negative emotions and undesirable behavior patterns |

| Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) | Psychotherapy that helps participants understand how negative feelings can lead to binge eating as a coping mechanism. It focuses on mindfulness, emotion regulation and distress tolerance |

| Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) | Psychotherapy that helps participants understand how problems with social interaction can lead to binge eating as a coping mechanism |

| Function | Example |

|---|---|

| 1. Enhance capabilities | Behavioral skills training including modeling, behavioral rehearsal, psychoeducation regarding binging, feedback, homework assignments |

| 2. Increase motivation | Individual sessions: behavioral assessment including triggers and consequences of binge eating behavior, contingency management. Exposure-based strategies and cognitive modification approach are also applicable |

| 3. Assure generalizations to the natural environment | Online consultations with the therapist, homework assignments; therapy tape review and analysis; follow-up sessions |

| 4. Structure the surroundings | Case management; family therapy and counseling |

| 5. Enhance practitioner capabilities and motivation to treat | Team work, supervision, consultation services |

| References | Study description | Behavioral therapy used | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

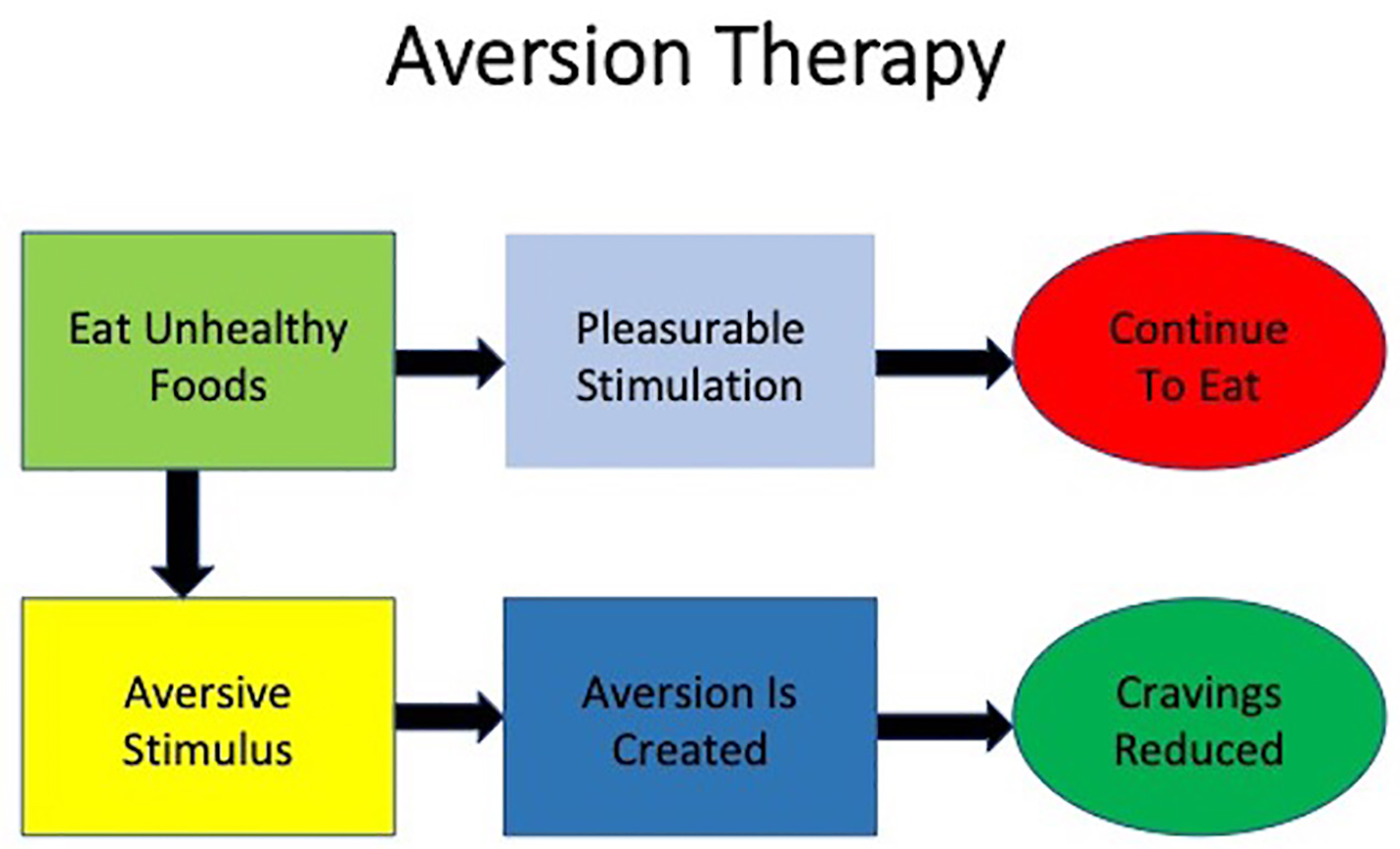

| Davidson (1975) [60] | Case study on avoidance of the stimulus | Aversion therapy | Reduction in poor eating and drug habits |

| Fairburn (1995) [58] | Randomized controlled study | Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) | Quicker management of eating disorders |

| Fairburn et al (1993) [48] | Randomized controlled study: use of three psychological treatments among 75 referred patients. There were two comparisons on cognitive therapy with interpersonal therapy and CBT | Interpersonal psychotherapy; behavioral; CBT | Changes in poor personal behaviors |

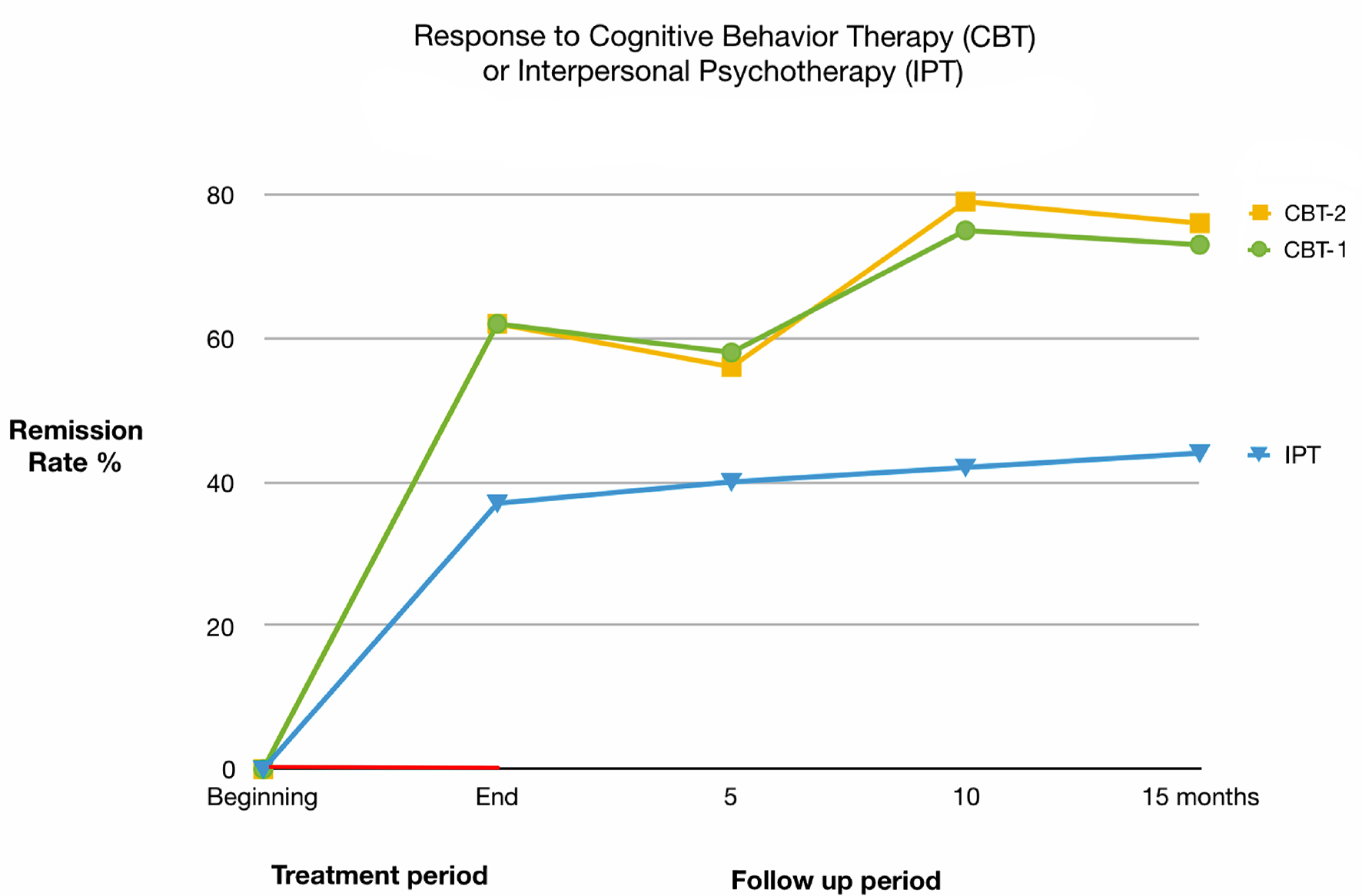

| Fairburn et al (2009) [44] | Randomized controlled study: comparison of two transdiagnostic CBT treatments among outpatients who were diagnosed with ED; one was focused on the features of the ED and the other was more complex involving interpersonal difficulties, mood intolerance and perfectionism. Total of 154 patients with ED who were slightly underweight were selected; study involved 20 weeks of treatment followed by 60 weeks of follow-up | CBT | Faster clinical outcomes with the patients |

| Hay et al (2009) [43] | Randomized controlled trial | CBT | Improved clinical outcomes |

| Mitchell et al (2007) [46] | Case study | CBT | Improved clinical outcomes |

| Murphy et al (2010) [45] | Randomized controlled trial | CBT | Improved clinical outcomes |

| Stiles-Shields et al (2012) [55] | Case study | Family-based treatment (FBT) | Treatment of binge eating in youth. Improved clinical outcomes |

| Rienecke (2017) [56] | Review article | FBT | Three phases of treatment, key tenets of FBT, and empirical support for FBT |

| Sysko and Walsh (2008) [57] | Case study | Self-help | Improves clinical outcomes |

| Wilfley et al (2011) [47] | Review article | Enhanced CBT and the socio-ecological model | Overview of current empirically supported treatments and the considerations for youth with weight control issues. Improved clinical outcomes were proposed |

| Atkinson and Wade (2015) [52] | A school-based cluster randomized controlled trial | Mindfulness-based approach | Usefulness of mindfulness in the prevention of eating disorders |

| Kristeller and Jordan (2018) [53] | Randomized controlled trial | Mindfulness-based eating awareness training program | Improvement in compulsive and emotional overeating is largely a function of ongoing behavioral change, suggesting that individuals who experience heightened spiritual well-being, may also be more fully engaging within the intervention. The clear relationship between increases in meaning, peace and faith and decreases in depression, anxiety, and program-targeted symptoms |

| Lock et al (2010) [54] | 121 participants, ages 12 through 18 years with DSM-IV diagnosis of anorexia nervosa except for not requiring ammenorhea. Twenty-four outpatient hours of treatment over 12 months of FBT or AFT. Participants were assessed at baseline, end of treatment (EOT), 6 months and 12 months follow-up post treatment | FBT, adolescent focused psychotherapy (AFT) | There were no differences in full remission between treatments at EOT. However, at both 6 and 12 months follow-up FBT was significantly superior to AFT on this measure. FBT was significantly superior for partial remission at EOT but not at follow-up. In addition, BMI percentile at EOT was significantly superior for FBT, but this effect was not found at follow-up. Participants in FBT also had greater changes on the eating disorder examination at EOT than those in AFT, but there were no differences at follow-up |

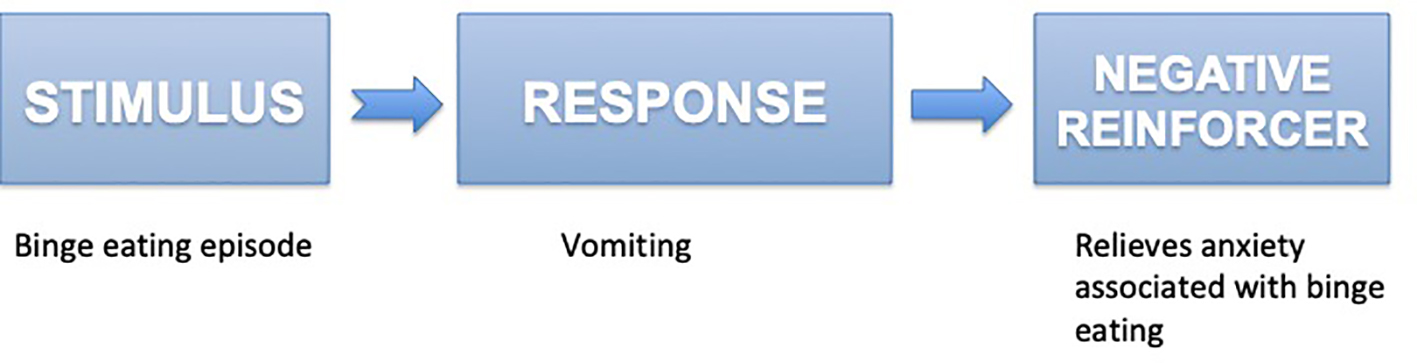

| Telch et al (2001) [49] | Randomized controlled trial | Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) | Treated women evidenced significant improvement on measures of binge eating and eating pathology compared with controls, and 89% of the women receiving DBT had stopped binge eating by the end of treatment. Abstinence rates were reduced to 56% at the 6-month follow-up |

| Linehan and Chen (2005) [50] | Review article | DBT | Conforms overall effectiviness of DBT |

| Iacovino et al (2012) [41] | Review article | Different treatment approaches | Article reviews research on psychological treatments for BED, including the rationale and empirical support for CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), DBT, behavioral weight loss (BWL), and other treatments warranting further study |

| Barrett and Chang (2016) [42] | Review article | Behavioral interventions | Article identified behavioral interventions targeting chronic pain, depression, and SUD and discussed their limitations |